Who Tells Our (Pandemic) Story?

Too often history is written by the powerful. A UConn anthropologist made sure the story of COVID-19 was chronicled by the rest of us. By Julie (Stagis) Bartucca ’10 (BUS, CLAS), ’19 MBAFour years.

This March marks four years since we were told to stay home, just for two weeks, to “flatten the curve.” March Madness was canceled. Tom Hanks tested positive. And fear was mounting as hospitals became packed with sick people, personal protective equipment became scarce, and, everywhere, people started dying of COVID-19.

While many of us were scrounging for hand sanitizer and figuring out whether it was safe to handle our mail, researchers at UConn and the world over wasted no time. They began designing better ventilators and masks, developing vaccines, improving logistics to deliver PPE.

And then there was UConn anthropology professor Sarah Willen, who quickly recognized we were living through history that should be documented in real time. Having journaled throughout her life, Willen figured a series of online questions prompting journal-like entries that recorded individual pandemic experiences would prove valuable to researchers in her field and in others, especially history.

Since its launch in May 2020, the ongoing “Pandemic Journaling Project” has amassed more than 27,000 entries, capturing the observations of and emotions experienced by real people across the globe throughout this mass event.

“Anthropologists aren’t the kind of researchers who know how to build an air purifier with, like, a piece of string and duct tape and a hair dryer. We don’t know how to do that sort of thing. But we do know how to create a welcoming, nonjudgmental space,” says Willen, who enlisted Brown University anthropologist Katherine A. Mason as her partner on the project. “So we did, and all sorts of people brought all sorts of experiences into it.”:

… I’m tired. It’s been more than two months of being home and I am so tired. I am trying to balance working from home full-time, being a surrogate teacher to a high school student and middle school student, and special education student. I am the hunter/gatherer for all household provisions, the bill payer, the chef, the best friend to my 13-year-old daughter, the therapist for my son, and the sounding board for my husband. I am the end-all-be-all for everyone and I am tapped out … I’m just so tired. I’m tired of working. Tired of schooling. Tired of this whole coronavirus. I remember when I thought being a working mom was tough. Now I am a working everything. -woman in her early 50s, June 3, 2020

… You know, I’m anxious. Professionally, my work insists I constantly puzzle through scenarios, lead solutions, repeat. I have never had to focus on one challenge 24/7 for months on end. It’s an unrelenting state of mind. And it can be tiring. I am also grateful. I will never again have this time with my family. I cherish the informal interaction, the reduction of chores, making family dinners, working out regularly, realizing, honestly, how much money and time I waste in “normal” life. I will miss a return to normal that takes away the simplicity of this time…. -woman in her 40s, June 4, 2020

I feel full of rage, sadness, and empty. My grandmother passed away from COVID. Words cannot begin to describe the amount of pain I feel from her sudden passing. Over the past three days, she is the 10th person who I have seen die from COVID. I just found out a few more close friends are hospitalized for COVID-19. It makes me wish I could have it so they could live. I actually did have it back in March 2020 but I was lucky, I only had a mild case and was able to move forward.

I just feel angry at times. Angry at how people are taking this as a joke and it comes at the cost of human lives. -woman in her 20s, January 12, 2021

“These stories give us an incredible window into how the pandemic challenged our sense of what it means to be human.”– Sarah Willen Think about it.

Most of us can remember the vacillating thoughts and feelings we experienced throughout 2020 and to varying degrees in the years since – and how those have evolved as the nation and world have emerged from a global crisis into something resembling normal (though whether it’s “new” or “back to” is up for debate). The tightrope we walked between anxiety and gratitude. Fear we’d contract the illness or lose someone we love, the sadness of isolation from loved ones, all mixed up with simple joys. Confusion over new public health information, or the rejection of those messages. The stress of navigating remote learning, even grocery shopping. The very real losses of life, of rituals, of the things that make families families. And, of course, the ways our own experiences and understanding and values differed from others’.

Willen says it’s all reflected in the entries. Everybody experienced the pandemic, but not everybody experienced it the same way. The journaling prompts were designed to capture those variations, to ensure the record contains the stories of people from all walks of life.

“Usually, history is written only by the powerful,” the PJP website states. “When the history of COVID-19 is written, let’s make sure that doesn’t happen.”

The project is a form of “archival activism,” which Willen and her team define this way: a strategic commitment to facilitating equitable history-telling in the future through inclusive collection and preservation practices in the present.

“It’s not that people who have influence and privilege necessarily mean to create inequitable historical narratives, but that’s what tends to happen if the historical record is thin on evidence about people who don’t have privilege or influence,” says Willen, who is also co-director of the Research Program on Global Health and Human Rights at UConn’s Gladstein Family Human Rights Institute. “Ordinary people deserve to have their stories included in the history books.”

“Individual people’s lives matter. Individual stories matter.”– Sarah Willen

Take the way U.S. history curriculum is primarily told from the point of view of white men and not Native Americans, for instance, or women, or enslaved people.

“If we have more robust data on everyday people – and especially everyday people from groups that tend not to be represented in the historical record – we’ll have so much more power. We’ll have so much more capacity to understand the specifics of how this pandemic affected particular communities, especially communities that have endured discrimination, exclusion, and structural violence, and put those specific, grounded stories in broader historical contexts.”

In the first phase of the project, from May 2020 through May 2022, the journal entries came from more than 1,800 people in 55 countries but primarily the U.S., with about half of American participants identifying as non-white. About 80 percent were women – getting more men involved was “a nut we never managed to crack,” according to Willen. Participants were surveyed on intake about demographics, occupation, beliefs and more, painting a detailed picture of each respondent while maintaining their anonymity.

The team employed the survey in addition to the journaling to thread the needle between anthropological and historical paradigms, protecting the privacy of human research subjects while ensuring the information would be useful to all who might want to delve into the data.

“It required a lot of thought and a lot of planning to bridge these different disciplinary concerns and generate an archive that would have value, not just in the near term, but also in the long term,” Willen says. And the possibilities for analyzing and disseminating the data are virtually endless.

“In their journals, real people are often struggling, in real time, to figure out how to be themselves in a world that’s no longer recognizable.”– Sarah Willen

So far, Willen, Mason, and colleagues in their field have published two special collections of research papers based on the project, examining topics including grief, loss, and isolation among health care workers; stress in Black women; and even journaling as a coping mechanism.

With a multitude of conclusions still to be drawn about specific groups, Willen, ever the anthropologist, is most excited to explore how the pandemic impacted individuals at their cores – in their struggles to live flourishing lives, or to live according to what she calls their defining commitments: those values and beliefs that make them who they are and without which they wouldn’t recognize themselves.

“In their journals, real people are often struggling, in real time, to figure out how to be themselves in a world that’s no longer recognizable.

“Suddenly, space wasn’t space. Time wasn’t time. Relationships, bodies, air – all these incredibly basic things suddenly became something we couldn’t rely on. And that made it really difficult for many of us to be true to our sense of who we are and who we want to be as individuals and in relation to everything around us,” says Willen. “Each person’s story matters on its own terms, for sure. Taken together, these stories give us an incredible window into how the pandemic challenged our sense of what it means to be human. It’s really easy to focus on darkness and terror and loss and grief in this public health crisis – and all that is definitely in the journals. But humans are more than that. Even when we’re experiencing loss or grief, we find ways to play. We find ways to entertain each other. We find ways to express love.

“I don’t think you can really tell the story of the COVID-19 pandemic and its impact on humanity without including all those expressions of creativity and playfulness and joy.”

April 2, 2021

April 2, 2021^ My mom died this week. She didn’t die of COVID, but she died *with* it. But she was still forced to die alone.

Her husband of 46 years is devastated. He was able to spend 15 minutes with her earlier in the day in full PPE. He wasn’t supposed to touch her, but he snuck his hand in anyway. And those lines on the picture are because we had to watch on FaceTime and take a screenshot.

You hear about these lonely deaths. But you don’t truly understand the depth of it until your family experiences it. It’s so complicated, and adds a layer of grief on top of what’s already an unimaginable loss. We will never recover from this.

March 25, 2022

March 25, 2022^ Two years ago when we abandoned our offices and started to work from home, I was surprised to find I missed the spaces around campus almost as much as I missed people. I’ve been back to work since July 2021 after I got vaccinated, but not all the buildings were reopened to the public. Last week I happened to walk through the education building, an airy and colorful space which I have always enjoyed. I stopped to take a picture because I was just so happy to be able to walk through this space again.

February 2, 2022

February 2, 2022^ Day #645 Haiku in Corona Time Entering new phase

With renewed optimism

The future is now

January 11, 2022

January 11, 2022^ After a year in which we had a new virus and no way to fight except with masks, social distancing, and staying isolated, having an effective vaccine is a game-changer for sure. Last year my friends and I hiked nearly every Sunday. None of us had access to the vaccine, and some of us are over 65 years old. We put on masks and quizzed each other about our carefulness in avoiding groups and people outside our households. We got lucky; none of us ever tested positive for COVID-19. Now we are all vaccinated and boosted, and we get into each others’ cars and drive out to the wilderness areas together with barely a qualm. Last Sunday I invited two new people to join our group. One of the more careful members of our group asked whether the additional people had been vaccinated. They had, and we had a wonderful time on a beautiful winter day.

What is the PJP?

Part anthropological research study, part historical archive, part large-scale mental health intervention, and part tool for self-reflection, the Pandemic Journaling Project (PJP) was launched by anthropologists Sarah Willen at UConn and Katherine Mason at Brown University. After completing an in-depth survey, participants are asked to answer several questions using text, images, and/or audio. The team then follows up via email or text – weekly from May 2020 through May 2022, now quarterly for those still participating – with a new set of questions.

Each time, participants are asked “How is the coronavirus pandemic affecting your life right now? Tell us about your experiences, feelings, and thoughts,” and a choice of two new questions inviting them to share their thoughts on topics ranging from their emotions to their living situations to international politics, the future, and even their experiences with the project itself.

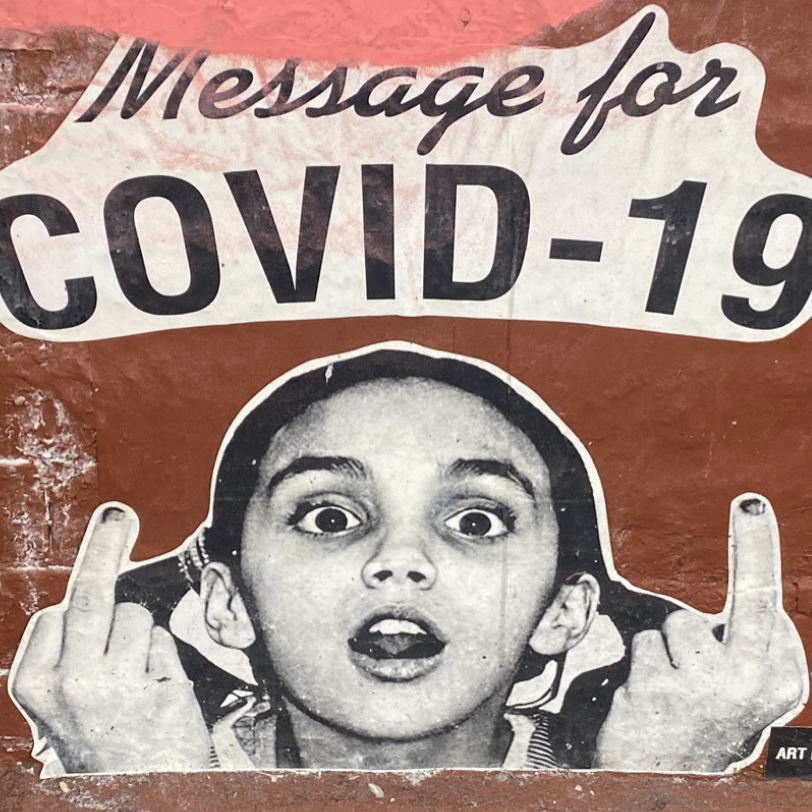

An interactive traveling exhibition has brought a poignant collection of images, writing, and audio from the journals to communities in Hartford, Connecticut; Providence, Rhode Island; Heidelberg, Germany; Mexico City, Mexico; and Toronto, Canada.

In December, a data set containing nearly 27,000 entries and important context about phase I of the project was deposited into the Qualitative Data Repository at Syracuse University, where for the next 25 years researchers can request access. In 2049, all records will become publicly available.

Sarah Willen

Learn more about the project and search thousands of “Featured Entries” at The Pandemic Journaling Project