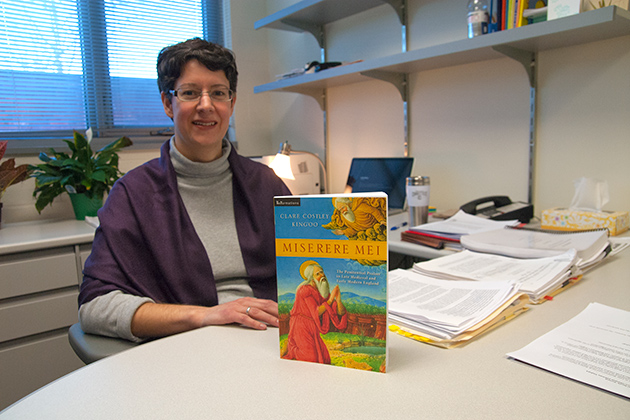

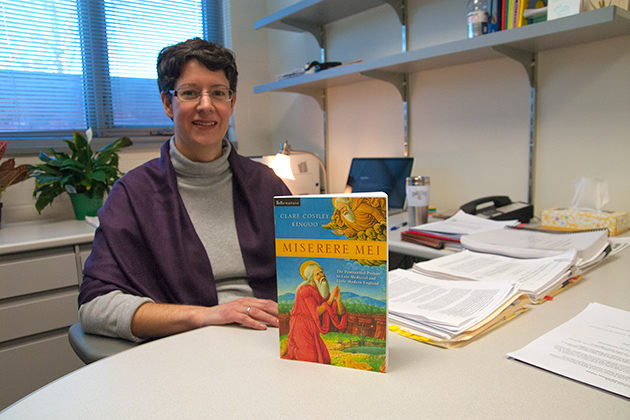

During her years as a Ph.D. student at the University of Pennsylvania, Clare Costley King’oo found herself drawn to a collection of dusty volumes in Penn’s Van Pelt Library. Little did she know that these obscure archives would ultimately lead her to write a book that would earn the 2012 Book of the Year award from the Conference on Christianity and Literature.

The book, Miserere Mei: The Penitential Psalms in Late Medieval and Early Modern England (University of Notre Dame Press, ReFormations series, 2012), was selected as the work that “contributed most to the dialogue between literature and the Christian faith” during 2012.

King’oo, an associate professor of English, received the award at the annual convention of the Modern Language Association in Boston last month. Previous winners include literary critic Northrop Frye and creative writers Umberto Eco and Madeleine L’Engle.

King’oo’s work was cited for combining “a meticulous study of a small body of scriptural texts with an illuminating exploration of their reception and influence over the course of centuries.”

King’oo educates her readers lucidly and advances scholarship in striking ways.

In Miserere Mei, King’oo examines the critical importance of the Penitential Psalms in England between the end of the 14th and the beginning of the 17th century. These seven biblical prayers, which express the individual’s sorrow for sins committed and ask for God’s forgiveness, are still part of Christian religious observances today. The book takes its title from Psalm 51, which begins in Latin “Miserere mei,” or “Have mercy on me.”

The Psalms have had a profound influence on Western culture, and inspired a wealth of creative and intellectual work during the period covered by King’oo’s book.

James Simpson, co-editor of the University of Notre Dame Press ReFormations series, says of Miserere Mei, “The project is perfectly designed and expertly executed. King’oo educates her readers lucidly and advances scholarship in striking ways.” Simpson is chair of the English department at Harvard University.

Dusty beginnings

The book had its genesis when King’oo, then a graduate student, began exploring some bound volumes of microfilm printouts of early English books on the shelves of a “closetlike space” in the library at the University of Pennsylvania.

“Most scholars go to modern editions of Shakespeare, Spenser, and Milton,” she says. “I was looking at representations of Bibles, prayer books, and catechisms in the form they were originally circulated.”

As she browsed these materials, the Penitential Psalms kept showing up, in various forms. “They seemed ubiquitous in early modern printing,” she says.

“Not only were they reproduced (sometimes with quite sexy illustrations) as prayers for repentance in the primers, but they were also expounded in sermons and commentaries, dilated in meditations, translated and paraphrased in verse, and converted into song,” King’oo notes in her book. That led her to question just why these psalms received so much attention.

The project called for her to acquire language skills in Latin, Middle English, and 16th-century German, and took her to rare book and manuscript collections in the U.S. and the U.K., including the Bodleian Library at Oxford University, where she had earned her undergraduate degree.

What emerged over the decade that followed is a study that illuminates the history of Christianity and religious plurality; the history of books and material texts; the periodization of Western culture; and even the history of sexuality – because, as King’oo observes, most instances of repentance in the Christian tradition have to do with sexual transgressions.

The central psalm (No. 51 in the Protestant tradition), and the one that gives the book its title Miserere Mei, is traditionally associated with King David and his adulterous liaison with Bathsheba. “This is the quintessential Penitential Psalm,” says King’oo.

A pivotal place in history

The Penitential Psalms took on special significance during the Reformation, when the early Protestants separated from the Catholic Church. At that time, penance and repentance were hotly debated terms, says King’oo: “What we see over the long haul is a shift from penance – which usually involves an act of atonement, such as fasting, or wearing sackcloth and ashes, or reciting the Penitential Psalms – to repentance, which in a Protestant congregation would be understood as a change of heart or mind, a turning away from sin toward God.”

These different meanings became polarized into over-simplified polemical positions that characterized the Catholic Church as being more about works and the Protestant Church as more about attitude.

“That’s why the Penitential Psalms are so interesting,” says King’oo. “They are one of the major sites where this debate takes place.”

The book also has implications for how cultural and literary epochs are defined. King’oo’s study led her to challenge conventional notions of when the modern era began, and of the Reformation as an intellectual watershed. Through her project on the seven psalms, she says, she came to understand that “the modern world emerged from very subtle shifts from what came before, and from rewriting and reappropriations rather than cataclysmic change.”

Additionally, the Penitential Psalms hold a pivotal place in the book culture of the period, and the evolution of how books were made and circulated. In her book, King’oo discusses the processes of copying, editing, illustrating, printing, and marketing, and the vast amount of labor that went into reproducing these seven short biblical prayers.

Implications for the digital age

Although the focus of her study is centuries-old, she says it also holds relevance for the digital generation. “We can ask the same questions of the digital world as we do of the world in which print technology emerged, and what that did for how theological concepts were understood,” she says. “What will digitization do for the way we understand any intellectual concept, not just theology?”

At the same time, she hopes digital works will not completely replace print materials, remembering those musty volumes that first drew her attention to this important group of psalms.

“I wouldn’t have embarked on this project without contact with that ghostly archive,” she says. “We see things differently when we can’t touch the page or inhale the dust!”