Even by Italian standards, Tiziana Matarazzo ’14 Ph.D. is exuberant as she talks about her work deciphering the remains of volcanic eruptions thousands of years ago. Her passion is so palpable, beaming through the small Zoom screen, it’s almost like she’s in the room. In fact, she’s 4,000 miles away, sitting in the sunny environs of her home by the seaside in southern Italy.

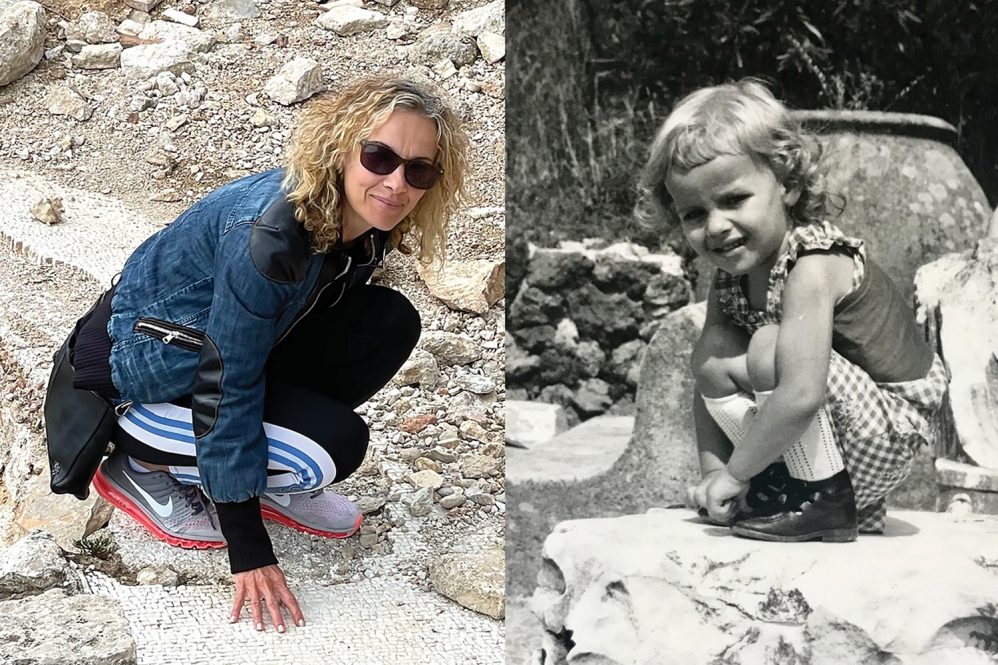

Matarazzo, who was born in Naples between the shadows of two volcanoes — Mount Vesuvius and the Campi Flegrei caldera — says she was inspired to do this brand of anthropological work because of her experiences being a child in such a richly historical city. “I grew up in an ancient town, and every time I would walk to school, I would pass a Roman mausoleum; and every time I looked at the sea, I saw volcanoes.”

After studying volcanology at the University of Naples Federico II, Matarazzo moved to the United States and enrolled at UConn, where she took a class called Old World Prehistory with the late UConn professor Robert Dewar. “After that, I just fell in love with archaeology — I was completely captured.”

Geoarchaeologists like Matarazzo — who lives mainly in Italy but conducts all her research out of professor Natalie Munro’s anthropology lab at UConn in the summers — apply geological methods to archaeological data to gain insight into how ancient human societies interacted with their environments. Matarazzo’s specific area of expertise is micromorphology, a technique for examining small-scale structures and textures of sediment and rocks that are not visible to the naked eye, allowing for detailed observations crucial for interpreting the material’s history and characteristics.

“Micromorphology can be used in different ways,” she says. “You can learn about past climates and different types of volcanic eruptions, but it can also tell you what people were doing in different places.”

Matarazzo’s doctoral thesis focused on the early Bronze Age, an important transitional period for humanity that was characterized by emerging social complexity. Specifically, she investigated the impact of the eruption of Vesuvius in 1995 BCE, which was actually larger than the more famous one that destroyed Pompeii in 79 CE.