You’re new to UConn. What made you decide to come here?

I know the previous director, Avinoam Patt, quite well, and it was a big draw that I’ve spoken to him throughout the years and he always raved about UConn. So that made it an appealing position to consider. After years of teaching at a small liberal arts college, I was also drawn to the new challenges and opportunities of working at a large research university.

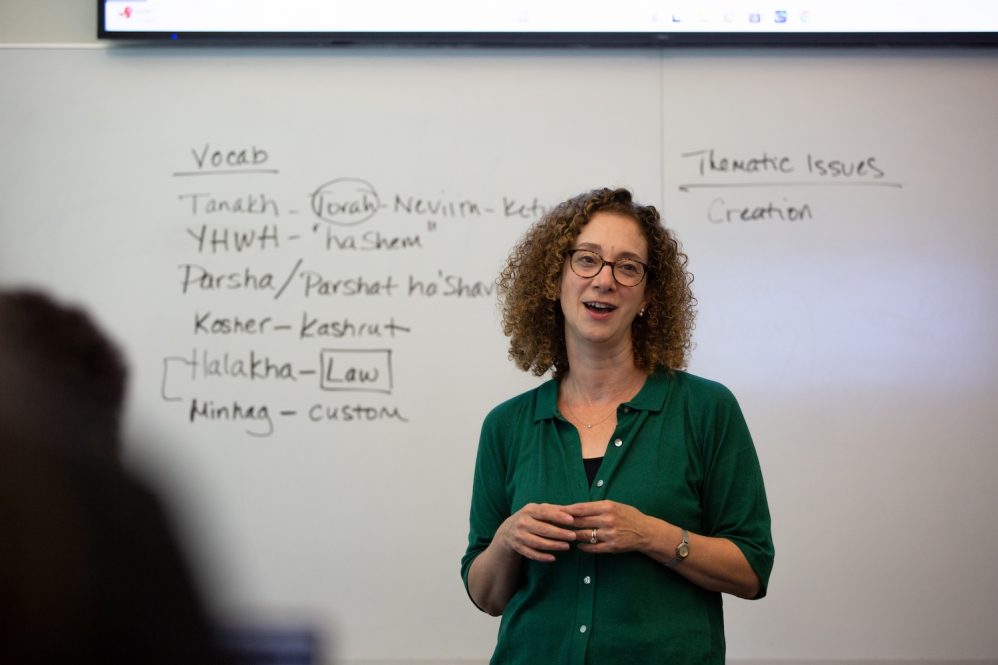

What do you teach and what do you like to teach?

I teach broadly in the field of Jewish history, and I especially enjoy teaching American Jewish history and American Judaism. In those courses, I try to weave in my own research and interests when possible, which makes it fun.

Some Jewish students may take my class thinking, “Oh, this will be familiar to me, right?” But it’s an opportunity for me to show them that there’s much more to learn.

Learning about Jewish history introduces students to all kinds of broader debates about migration, race, religion, cultural production, state structures, prejudices, minority rights, and civil rights—topics they might not have thought about in connection to Jewish history. Judaic Studies creates opportunities to learn about Jews and Judaism, but it also leads students to lots of other issues, which we can explore together. I find that really exciting.

Could tell us about your research?

My field is broadly defined as modern Jewish history, but my research is on American Jewish history and American Judaism.

My first book focused on soldiers’ services in the First World War. The American military wanted to create a more well-behaved force, to keep soldiers in line, engaged, and out of trouble. The military came up with the idea that soldiers needed to participate in morally uplifting activities—like singing, sports, and educational classes—to be good citizens and good soldiers. So, they hired the YMCA to provide those services.

Instead of protesting about the Protestant YMCA getting this role, the Jewish Welfare Board, a Jewish organization, and the Knights of Columbus, a Catholic fraternal organization, volunteered to be counterparts to the YMCA. In the book, I argue that they ended up changing the government’s conception of religion and the roles of Judaism and Catholicism within these government programs. By the end of World War I, the government perhaps didn’t celebrate, but at least clearly advertised in their propaganda, the partnership among Protestants, Catholics, and Jews in the service of the country.

My current research project focuses on the history of Passover in the United States. I’m interested in exploring how both Jewish and non-Jewish communities, particularly Christian ones, have adapted and adopted the holiday and its rituals to express various social, political, and cultural concerns throughout the 20th century.

I am also interested in in the history of Jewish-Christian relations in the United States, especially in 20th century projects intended to promote Jewish-Christian dialogue – that is the research project ahead.

What are some themes in your field right now?

I am one of the co-editors of the journal American Jewish History, so I get to read a lot of the newest scholarship in my field. Some of our recent issues have included articles about Sephardic and Mizrachi history in the Americas, Jewish farm collectives, policies on immigration and disability, 19th century religious school curricula, transnational trends in Jewish liturgical music, and Emma Goldman’s love of opera. Because Judaic Studies is an inherently interdisciplinary field, there are always many directions of research – and that is just in the field of American Jewish history. Judaic Studies also includes scholars who study everything from Biblical literature and the ancient world to medieval Jewish mysticism, gender studies, Holocaust studies, Israel studies, contemporary Judaism – and absolutely everything in between. I am not sure that there is any one topic that drives the entire field, but that diversity is part of what makes it dynamic and exciting.

Why do you think it’s important for large universities to have a center that focuses on Jews and Judaism?

I think that higher education has an obligation to serve the public good, and I believe that is particularly true at a public institution. It was part of what drew me to UConn—there is an explicit responsibility to not just teach in an “ivory tower” or a removed academic setting, but to think about how what we teach can be shared with, useful to, and interesting to the public at large.

While students are perhaps the first audience we’re speaking to, I think it’s important to consider how a public institution of higher education can serve the public. The Judaic Studies Program and Center for Judaic Studies and Contemporary Jewish Life can offer classes, events, programs, and research projects that help to meet that responsibility.

I think people want educational and intellectual opportunities. They want to learn new things and to be introduced to new ideas. And at this moment of ongoing violence in Israel and in Gaza, and growing concern about antisemitism in the United States and around the world, learning about Judaism, Jewish culture, and Jewish history feels particularly relevant.

What do students who aren’t majoring in Judaic Studies get from your classes?

Jews can serve as a lens through which we examine larger social structures and institutions, and you never quite know where that journey will take you. If someone takes a class on Jewish history—like my class on American Jewish history—and they love it and decide to focus on Judaic Studies, that’s fantastic. I very much want to expand the major in and minor in Judaic Studies at UConn. But if students take a class with me and then go on to explore questions about immigration in the United States, or the forces that lead people to migrate from place to place, or any number of other issues that they might encounter in one of my classes then that’s also great.

In the humanities, our ultimate object of study is humans and human societies. So, if my classes can provide both a window into a particular set of human experiences and tools to help students think critically and analytically about the varieties of human experience, and about the different ways that people have made sense of the world and organized their societies over time, then that’s fantastic.

Are there any misconceptions about your field?

The biggest misconception I’ve encountered is that Judaic Studies is only for Jewish students. I’m always happy when someone comes to one of my classes because they have a personal connection to the topic and want to explore it. But just as there’s no expectation that you must be Russian in order to be interested in Russian literature or history, just as an example, you certainly don’t have to be Jewish to be interested Judaism and Judaic Studies.

You can want to study something simply because you’re curious. It’s great if you find a personal connection that draws you to a class, but sometimes that connection can be purely intellectual. Intellectual curiosity is enough—the classes are for anyone who’s interested.

In your time here so far, what’s your favorite spot on campus?

I don’t have a favorite spot yet, but I love how beautiful the campus is, and I am really enjoying watching the fall leaves change color. I have come to bond with the Dodd Center, which is where the Center for Judaic Studies is located. Students and faculty are welcome to come in and say hi!

This Q&A is part of CLAS Visionary Voices, a series highlighting the College’s new academic leaders and their innovative visions for education, research, and outreach at UConn.