This is the summer of raspberry pie and pool noodles for Oliver Mackinnon ’25 (ENG) and the other members of UConn’s Underwater Robotics club.

Sure, that makes it sound like they’re winding down an afternoon of swimming with a berry-filled pastry, but Raspberry Pi for them is a small computer they used last academic year to control one of two underwater robots they built from scratch.

And pool noodles, well, they’re exactly what one might imagine, except this group of about 10 students has studied the properties of those dollar store staples beyond just using them for fun.

“If we put a pool noodle on any of our components, what happens when we send it down,” Mackinnon asks. “The noodle gets compressed the deeper the water because the water pressure goes up and that wrings the air out of the noodle, making it not buoyant anymore and unusable as a flotation device. We have to use special marine flotation, which makes it more challenging and more expensive.”

The challenges of building an ROV – or remotely operated vehicle, which NOAA Ocean Exploration defines as an unoccupied, maneuverable, underwater machine – don’t stop there.

“Designing an underwater robot is more like building a drone than something that rolls around on land,” Mackinnon explains. “It has to rotate up and down and move side to side. There’s buoyancy at the top to keep it level and make sure it both returns to an upright orientation and doesn’t sink. Radio waves don’t go through water, so you have to run a physical tether that needs to be neutrally buoyant, and waterproofing everything makes it all the more challenging.”

So as Mackinnon and his team no doubt get some swimming in this summer, indeed they also are thinking about Raspberry Pi and pool noodles.

‘Teaching people how to do things’

Mackinnon started UConn’s Underwater Robotics club in spring 2023 and spent the first few months solely lining up funding from UConn’s Krenicki Arts and Engineering Institute, the National Institute for Undersea Vehicle Technology, and the Undergraduate Student Government before soliciting members last fall.

He had three goals, he says: teach members the skills they’d need to build an underwater robot; give people like him a hands-on project, a place where they could get their hands dirty; and participate in the international MATE ROV Competition, which is held annually each spring for students elementary-aged to college.

Back in high school, Mackinnon and his team from The Sound School in New Haven earned a high enough ranking in the MATE ROV regional competition to get to the international stage. It was fun then, he says, surely it would be fun now.

With 32 UConn students from majors including mechanical and computer engineering, mathematics, and molecular and cell biology – one even enrolled in the Neag School of Education – a core group of about 10 set to work, first building what they call, Minnow Bot, a 3D-printed, hand-sized, red submarine reminiscent of Rocket from the children’s television show “Little Einsteins” from the early 2000s.

“Most of the people who came into this club had no underwater robotics experience at all and minimal experience doing electronics and CAD,” says Mackinnon, who’s now the club’s co-president. “A significant part of this year was me teaching people how to do things because most of this is from what I learned in high school.”

Colin Sheardwright ’27 (ENG) says learning the 3D modeling program OnShape was his favorite part, while Joshua Okoli ’25 (ENG) liked assembling – the measuring, cutting, fitting, sanding to get pieces into place.

“There’s so many things that go into making an underwater robot,” Okoli says. “The 3D modeling, determining a parts list to order, researching where to get supplies, the computer programming to get it to operate, designing the electrical components, never mind the actual assembling of it.”

“And the testing, which we really didn’t even get to,” Sheardwright adds.

Minnow Bot was small enough to fit in a bucket, and when it passed that test, in April it explored the shallow depths of Mirror Lake.

As for Bigo Bot

Building Minnow Bot gave the students a way to practice their newfound skills, as procuring the parts needed for the ROV they’d hoped to compete with took much of the fall semester.

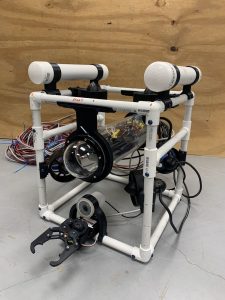

In labs at the Krenicki Institute in the School of Fine Arts, they designed plans for a roughly 2-by-2.5-foot PVC cube, with six thrusters, stabilizing flotation, a camera, a claw arm, and a 60-foot tether – collectively and affectionately named Bigo Bot.

When the time came to work at soldering stations and use saws to cut PVC, they moved into the Hacklab workspace in the College of Engineering.

Mackinnon says one of the critical parts of Bigo Bot is the acrylic tube fastened in the center of the cube, which is rated for a depth of 60 meters because much like pool noodles deflate in deep water, so won’t cheap plastic. The tube serves as the heart of the robot, suspending and protecting all its electrical components.

Penetrators run the wires out of the tube and a gasket compressed against the wires keeps out water. Mackinnon says actual waterproofing requires the use of petroleum jelly, mineral oil, and marine epoxy, each serving as a barrier to water that’s desperate to push itself inside.

“Right now, Bigo Bot can pick something up and bring it to the surface. It has full range of motion and is able to turn side to side, move up and down. It can record video. It can take pictures. It’s going to have a pressure sensor on it that can tell us how deep the water is and probably a thermometer too at some point,” he says.

In the shop, it runs off a 110-volt AC current to a 48-volt DC current power supply; in the field, a car battery will power it.

“There are so many industries, many right here in Connecticut, that are looking for technology like this,” Mackinnon adds. “I got an internship at Electric Boat this summer, probably largely because of this club.”

Next year is for experimenting, adding members

The idea of the MATE ROV Competition is to design and build an underwater robot that functions and can perform certain tasks. It’s also meant for students to design and build technology that could be marketed commercially.

Mackinnon says that could mean using an aluminum frame, because it doesn’t rust like other metals, instead of PVC pipe to give it a more finished look. It also could mean simply painting a few components.

Since UConn’s club, which is accepting new members, got started building Bigo Bot late in the academic year and because funding was tight – the final robot cost around $1,500 – students didn’t make it to the 2024 competition. This first full year of the club was a learning year, they say.

And that means all the computer code they wrote to bring Bigo Bot to life can be used in the coming year, along with whatever parts they want to cannibalize, including the acrylic tube, which alone was $300. It’s likely though things like the claw grabber will be redesigned.

“Next year, we’ll experiment a bit. We want to make our own thrusters,” Mackinnon says, grabbing a dry erase marker to sketch out an idea he’s had since high school.

“In a traditional thruster, the propeller spins around a central axis and the motor is inside. I want to make a propeller that spins around the outside, so inside the thruster is just completely empty. It’s called a rim jet thruster.

“When a normal propeller setup encounters algae, for instance, it gets entwined in it. With a rim jet thruster, it’s going to get sucked through and won’t get wrapped around it. When Minnow Bot went in Mirror Lake, and there’s lots of algae in there, it had significant trouble. Every few minutes it would get stuck, and I’d have to pull it out, take the algae off, and pretty much reset it. That wouldn’t be an issue with the type of thruster I want to make,” Mackinnon says.

Sheardwright notes that being able to test the robot is a critical part of their process, one they couldn’t fully realize last year because of time and place – there simply isn’t a pool nearby they could use readily to test; campus pools, they initially found, require rental and come with a significant price tag.

Next year, though, they’ve secured use of the pool in UConn’s Wolff-Zackin Natatorium.

“What’s nice with Minnow Bot is you could put it in a bucket and drive it around. But the other robot is big. It’s 60 cm in diameter and isn’t going to fit in a bucket,” Mackinnon says. “We can test the waterproofing. We can test the motors to make sure they work, but we really can’t maneuver it around the way we would want to.”

“I mean, I live on a lake,” Sheardwright hedges when asked if Bigo Bot has any travel plans this summer.

“Oooo,” Mackinnon responds.

“We could, yeah, it could actually work. We have a dock and it’s pretty clear.”

Bigo Bot may see testing yet.

“Ideally, we would have competed in this year’s competition and it’s sad that didn’t happen. But, honestly, I’m still so proud that we made what we did this year,” Mackinnon says. “I was pretty much the only person who had experience coming into this, and I think getting a working robot was a great accomplishment. I’m happy with that.”