Between scorching summers and unprecedented storms, the consequences of climate change have crashed down on Connecticut in recent years. Policymakers, urban planners, and resource managers are needing to make decisions with new threats in mind: more extreme weather events, heat, and sea level rise.

This last threat is something James O’Donnell, professor of marine sciences and director of the Connecticut Institute for Resilience & Climate Adaptation (CIRCA) at UConn Avery Point, knows a lot about. A physical oceanographer, his research focuses on circulation and mixing in the ocean. These factors influence how sea levels will respond to climate change.

Forecasting Flood Risks After Hurricane Sandy

In 2018, the Connecticut legislature passed a bill urging UConn and the Connecticut Department of Energy and Environmental Protection (DEEP) to develop guidelines advising state leaders on how to plan for sea level rise. O’Donnell was already in position on the UConn faculty and was ready to spearhead the effort.

“Superstorm Sandy kind of focused people’s attention on the impacts of flooding, and the expectation that it may increase,” O’Donnell says.

O’Donnell led the initiative to predict Connecticut’s future sea level rise and translate the data into models for community planning – no simple task, since sea level rise is impossible to predict with 100% certainty.

His mathematical analysis found that Connecticut’s potential sea level rise by the year 2050 could vary enormously. The low end of the range was six inches; the high was about 25 inches.

Simplifying these figures to an average that’s in the middle – roughly nine or 10 inches – is tempting. But policymakers and planners need to factor in various costs and benefits as they decide which figure to use, weighing cost and feasibility against actual risk. If sea levels did exceed their selected threshold, they’d be – quite literally – sunk.

Ultimately, O’Donnell advocated for towns to plan for a 20-inch sea level rise by 2050. That number, he explains, is 95% certain to exceed the actual rise.

That’s a good thing, because it’s far better to have built too high than not high enough, especially as the seas continue to rise.

The legislature adopted this recommendation and required towns planning to construct new roads or buildings with state or federal funds to “basically, build them 20 inches higher,” O’Donnell explains.

The report “has been very influential,” he says. “We spend millions and billions of dollars on this kind of stuff, and it will reduce future risks for things that we care about.”

Mitigating Disaster, Before It’s Too Late

In addition to residences and roads, O’Donnell names electricity substations (which send energy to homes and businesses along the power grid) and water treatment plants as two coastal facilities that need protection from the rising tides.

“In Connecticut, all of the water treatment plants are located along the shore,” he explains. “Water treatment plants are not a sexy thing – but if they break, things are really disastrous pretty quickly.”

During Superstorm Sandy, he recalls, many water treatment plants and substations in the region were flooded or almost flooded. Flooded electricity substations can explode, destroying the region’s power infrastructure and costing a fortune in repairs. And flooded water treatment plants stop being able to process sewage before it’s released into the ocean, sometimes also suffering costly electrical failures.

“It’s bad news,” O’Donnell says simply.

‘Community Resilience’ — Not Just for Coastal Towns

Coastal communities aren’t the only ones at risk of increased flooding in the coming years. Rising sea levels and storms will also surge into Connecticut’s rivers, potentially causing flooding all around the state. Because of this, CIRCA teams are also carrying out resilience projects in cities like Danbury and Hartford.

O’Donnell’s sea level report was just one example of the influential research of CIRCA. A collaboration between UConn and DEEP, two powerhouses of environmental expertise, CIRCA is an institute designed to help steer climate-smart policymaking and provide environmental outreach education to communities across the state.

Since the institute’s inception in 2014, O’Donnell and other CIRCA researchers have been involved in various resilience projects around Connecticut. The CIRCA-led initiative Resilient Connecticut was established to focus on the vulnerable communities of New Haven and Fairfield counties, implementing strategies such as living coastlines and transit-oriented economic development; now, it is expanding its recommendations to the whole state.

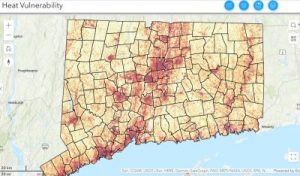

CIRCA researchers have also developed tools like the Climate Change Vulnerability Index (CCVI), a mapping tool that combines built, social, and ecological factors to identify areas that are vulnerable to flooding and heat-related impacts of climate change, and the Connecticut Environmental Justice Screening Tool, which allows users to explore the environmental health and socioeconomic conditions of regions across the state.

“This is not coastal resilience alone,” he says. “It started that way because of Sandy, but now we call it community resilience.”

O’Donnell, who has worked at UConn for 36 years and researched ocean physics for even longer, describes the feeling of becoming an overnight celebrity as his research suddenly became uber-relevant to lawmakers and urban planners.

“We’ve been measuring this stuff [ocean mixing and sea level rise] and figuring out analysis techniques for years,” he says. “We’d publish papers in journals – they’d get read by like 200 people, if you were lucky. But now, with questions about climate change and its impacts, CO2 sequestration in the ocean, and the environmental impacts of wind power – these are all associated with mixing in the ocean.”

“People care now,” he continues. “It’s not just you and your friends in the Physical Oceanography Journal club anymore, you know?”

As the stakes of climate change research continue to increase, CIRCA is poised to continue providing decision-makers with evidence and expertise, keeping Connecticut communities safer.