A lifetime of activity can gradually erode the cartilage that cushions our joints. Someday, we might simply inject a gel to repair it, University of Connecticut researchers report in the Oct. 6 issue of Nature Communications.

Decades of running, climbing and jumping can wear away the cartilage that cushions our joints, eroding it until bone rubs against bone, a painful condition called osteoarthritis. More than 500 million people around the world are affected by osteoarthritis, and the knee is the most commonly afflicted joint, according to the World Health Organization. Surgery to remove or repair damaged cartilage of the knee is common. But these surgeries are not always successful, and adults rarely regenerate cartilage.

Biomedical engineers have solutions to part of the problem: there are scaffolds that are compatible with human cartilage, and encourage regrowth when implanted into the knee. But such scaffolds still require surgery.

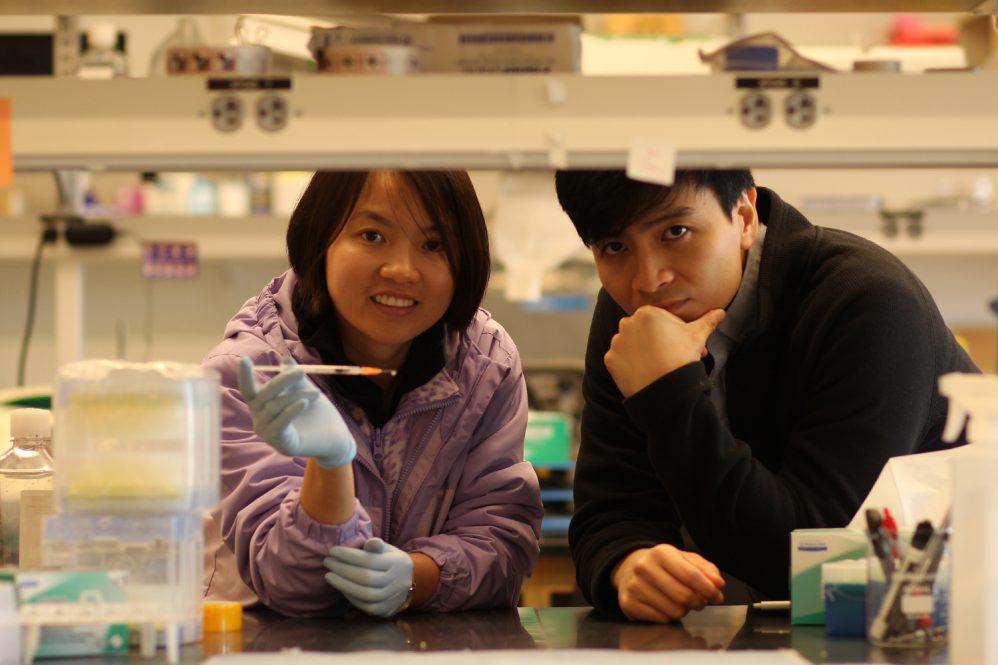

“A solid scaffold [that encourages regrowth] is really nice. But making it injectable would much reduce patients’ pain and suffering,” says UConn biomedical engineer Thanh Nguyen. His team, including researchers from UConn, UConn Health, Peking University School, and Eli Lilly, have now designed such an injectable treatment.

Nguyen’s lab specializes in working with piezoelectric materials compatible with the body. Piezoelectric materials generate mild electric fields when they are flexed or bent. These electric fields mimic those produced by the body itself when it recruits stem cells to heal damaged cartilage. The researchers decided to try the same technique—piezoelectric stimulation—but in gel form. Instead of requiring surgery to insert a solid scaffold, the gel could be simply injected into the knee, a much less invasive procedure.

Nguyen’s graduate student Tra Vinikoor and colleagues took poly-L-lactic acid, a piezoelectric material, and spun it into tiny fibers that they mixed into a gel. They then injected the gel into the knees of rabbits with damaged cartilage. After two weeks they began applying ultrasound five times a week to activate the piezoelectric fibers. And the rabbits’ cartilage grew back. After about two months, the team saw re-formed, functional cartilage in the animals’ knees.

The technique seems to work about as well as implanting a solid piezoelectric scaffold, but without the complications of surgery. The researchers hope to test the technique in larger animals more akin to humans soon.

The project was funded by the NIH (grant number R21AR074645 to T.D.N. and partially by grant numbers R21AR078744, R21AR080919, and R01AR080102 to T.D.N.)