Raina Jain didn’t know that she was allergic to honeybees until she was stung on her foot while setting up an experimental bee hive at her home. The reaction, she says, was so bad that she couldn’t walk for two weeks.

It wasn’t Jain’s first time interacting with bees. In fact, she’d long immersed herself in the complex world of honeybees, beekeepers, and apiaries. It was, however, her first time not wearing a beekeeper’s suit. Allergic reaction aside, the experience didn’t deter Jain’s interest in the tiny insects. Far from it.

Last August, her work with bees led one Forbes Magazine contributor to write that “a 17-year-old from Connecticut is saving honeybees.” Not only are honeybees critical pollinators that play a huge role in food systems, they’re worth saving, says Jain, who is from Greenwich and is currently studying remotely during her first year at UConn.

“I’ve been brought up with the principle of ‘live, and let live,’ to value every life, no matter how small,” says Jain. “You hear all these things on the news, but you don’t realize how important they are until you see them firsthand. And so, I kept hearing that bees are in danger, and the population is decreasing, and things like that, but I didn’t really understand what that meant until I saw a bee farm firsthand, and I saw hundreds of empty and absconded hives and piles of dead bees.”

The culprit behind much of the bee devastation is the “Varroa destructor,” a tiny mite that attaches itself to and feeds off of a honeybee. The mites can only reproduce within honeybee colonies, and their presence spells bad news for the colony. Varroa mites weaken the bees, cause physical malformations, and lead to virus transmission and reproduction issues. The mites cause significant bee population losses worldwide each year, taking a toll on individual beekeepers and apiaries as well farmers and the economy in general, as bees help to pollinate about 80 percent of the world’s plant life.

Still in high school at the time, Jain learned about the Varroa plight at a science fair lecture and was struck by the tiny mites and the huge problems they cause. Then, she took action.

“To see all these bees dying for no fault of their own, I thought that was just not right, and that’s when I decided to take it into my own hands and try to think of a tangible solution to that problem,” she says.

Jain reached out to the lecturer, the University of Maryland’s Samuel Ramsay, and read every research paper on honeybees she could find. She built a prototype of a device and created a gel-like solution relying on a substance called thymol – a naturally occurring pesticide that, at low concentrations, doesn’t hurt the bees but destroys Varroa mites – and the prototype failed. But she was undeterred.

“I still have that gel with me today, because I sometimes just look at that and think, ‘Raina, this whole experiment, this whole company, everything started from that first step,” she says.

Fast forward to today, and her company – HiveGuard – is in its final testing stage, recently deploying 100 of its thymol-depositing hive entryways to beekeepers in California, Florida, and North Carolina.

Honeybees move in and out of their hives hundreds of times a day as they forage for food. Jain’s device works by depositing small amounts of thymol onto the bees as they pass through the entryway of the hive, slowly building up a concentration of thymol that kills the Varroa mites, but causes no adverse effects for the bees. The device, according to Jain’s website, is “temperature-independent, does not contaminate the honey, and does not need any additional maintenance after a quick one-time installation.”

After her debut in Forbes, Jain says she was flooded with inquiries from beekeepers looking to learn more about her device. She has 4,000 devices already reserved for when her company begins full-scale production after their current round of testing.

“That article just went viral among beekeeping communities,” she says. “And I remember waking up one day and just having thousands of emails, you know, like this has never happened to me.”

While the prospect of launching a company as a teenager and starting full-time studies at a major research university at the same time is understandably daunting, Jain is remarkably unfazed. There were a lot of signs along the way, she says, that showed her that entrepreneurship would ultimately be her path.

“I was always that lemonade-stand girl, trying to make extra money on the side,” Jain says, “but also, I feel like it is such an untraditional path to go toward. For me, to build something from nothing and see that grow, I think, is just beautiful. In anything that you do, whether it’s a science experiment, or a product that you’re building, to just start off with one idea and slowly and slowly build that into something tangible, something you can see, something people want – I think that process itself is very beautiful.”

Her entrepreneurial spirit is also a major factor in her decision to choose UConn, where she has yet to decide on a major but is leaning toward economics or engineering, with a minor in computer science.

“I knew from the start that UConn would be the place that I wanted to go, because I felt like they were so driven to help every individual kid grow,” she says. “I’ve always prioritized my business, but I think what I love about UConn is that they’re so incredibly supportive of it. They keep encouraging me instead of discouraging me, which I found to be very common of people outside of UConn, people are like, ‘Raina, focus on school, this is not the time to do this, focus on your studies,’ and things like that, which I am, but I’ve gotten so much encouragement from UConn to do both, and I know that they’re here to support me along the way.”

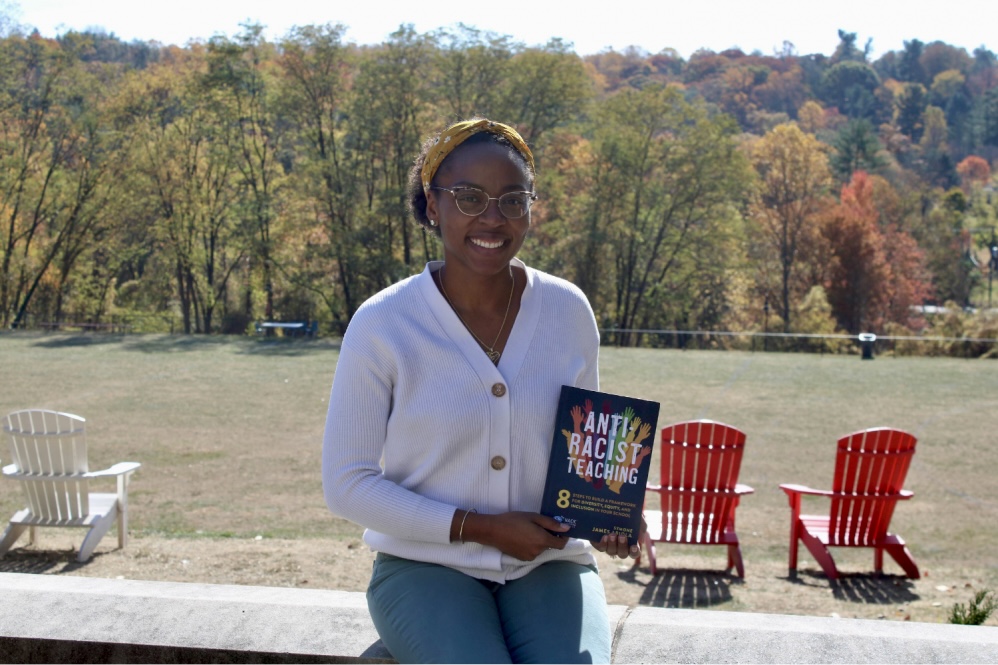

She’s also a member of the inaugural cohort of Freshman Female Founders through UConn’s Peter J. Werth Institute for Entrepreneurship and Innovation, a pilot program aimed at engaging first-year undergraduate women with mentorship, networking, and resources to support their entrepreneurial journey. Supporting women entrepreneurs, particularly fellow women of color in STEM fields, is very important to her, Jain says.

“I am so incredibly passionate about making women in STEM making their voices heard, especially because I remember when I was going around the country giving presentations on HiveGuard, attending these panel discussions and presentations and things like that, I would sit on a three-hour conference call, I’d be the only woman of color, who is 17 years old, and I wouldn’t say a word,” she says. “I started forcing myself to speak up and say things that were on my mind, and so slowly I was able to come out of that and become the person I am today, but that did take a lot of courage and stamina. And I just felt like, just to have a woman standing next to me in that conference call, in that presentation, you just felt different, like you were in it together, almost.”

Jain is “one in a million,” says The Werth Institute’s director, David Noble.

“Most students have entrepreneurial potential, and it is our job to shine a light on that or open up that aspect of their life,” Noble says. “We spend a lot of time teaching students how to capture value from their potential. Raina is different. She has the eye of the tiger, she has the thing you can not teach, so you just try to support it – find ways on the margin to help, make her day a little easier.”

Jain says that other students, regardless of age or experience, who have a passion or an idea shouldn’t ignore their dream.

“If you’re scared, if you don’t know how to start, just start – reach out for help, and just start,” she says. “These dreams that you have as a kid, don’t let anybody talk you out of it, and don’t let anybody tell you that it’s not possible, because it is, and you only know it if you try.”