More than 700 students enroll each semester in Principles of Biology, Biology 1107, using a textbook of more than 1,300 pages, with chapter headings ranging from the chemical basis of life, animal nervous systems, and green algae and land plants, to ecosystems and global ecology.

Biology majors enrolling for next semester in the laboratory section of that class will be among the first students to benefit from a series of five instructional animations created by School of Fine Arts students from the departments of Digital Media and Design (DMD) and Art and Art History.

The animations will help students better understand complex biological systems keyed to the teaching of basic science concepts by faculty in biological sciences, and assist majors in related disciplines, such as nursing and nutrition, as they move into advanced science classes.

Watch the ‘Human Heart’ animation here.

“Using pre-made resources, you almost always have to make compromises in the curriculum you’re presenting to the student, or you have to tell them to ignore part of the video,” says Christopher Malinoski ’05 (CLAS), ’13 Ph.D., manager of the Biology 1100 laboratories. “Having an opportunity working with students where we could have tailor-made animations specific to the content the way we teach it was very appealing. It makes the delivery of the information that much more successful for our undergraduate students.”

Today’s students are a generation of ‘visual learners,’ and developing new animation, video, and other visual resources will continue. — Christopher Malinoski

Malinoski and graduate teaching assistant JD Tamucci ’16 (CLAS) sought assistance with developing scientific animation after learning about such a class offered last spring by Anna Lindemann, an assistant professor in DMD, who had received requests from STEM faculty for assistance in presenting research findings. Similar requests for assistance from STEM faculty for scientific illustration had come to Alison Paul, an assistant professor of art.

Lindemann and Paul developed a course titled “Scientific Visualization” to bring together a select class of DMD and art students. The class undertook collaborative projects in groups with at least one animator from DMD and one illustrator from art. In the end, four out of the six art students were either double majors in science disciplines, such as chemistry and biology, or science majors with a minor in art.

“What’s so exciting about this class is that it really is a collaboration where everyone is bringing something to the table,” Lindemann says. “Alison [Paul] is supporting the illustration work students are doing, I am supporting the animation work based on the illustrations, and our whole class is relying on input from science faculty and staff to create accurate and engaging scientific visualizations. It’s everyone feeding off each other.”

The faculty initially discussed a list of potential animations students could create for BIOL 1107 instruction. The five animations, some with narration, that the DMD and art students created are between three and five minutes in length and include:

• “The Human Heart” follows the path blood takes through the heart, driven by the heart’s electrical system. Illustrations by Hayley Joyal ’18 (SFA), an art and art history major, and Emily Wadas ’19 (CLAS)/(SFA), a double major in ecology and evolutionary biology and art and art history. Animation by Sarah Shattuck ’20 (SFA), a DMD major.

• “Tonicity” covers the qualities of an extracellular solution and how they influence water movement into or out of a cell by osmosis. Illustrations by Ziael Aponte ’18 (SFA), an art and art history major. Animation by Helena Sirken ’19 (SFA), a DMD major.

• “Cellular Respiration” describes the processes in cells that convert nutrients into biochemical energy in the form of adenosine triphosphate. Illustrations by Mary Accurso ’19 (CLAS), a molecular and cell biology major with a minor in studio art. Animation by Aaron Kane ’19 (SFA), a DMD major.

• “Joints and Articulations” depicts the varying degrees of movement at the junction of bones. Illustrations by Juliette Thuillier ’18 (CLAS), an ecology and evolutionary biology major with a minor in studio art. Animation by Rebecca Henderson ’18 (SFA), a DMD major.

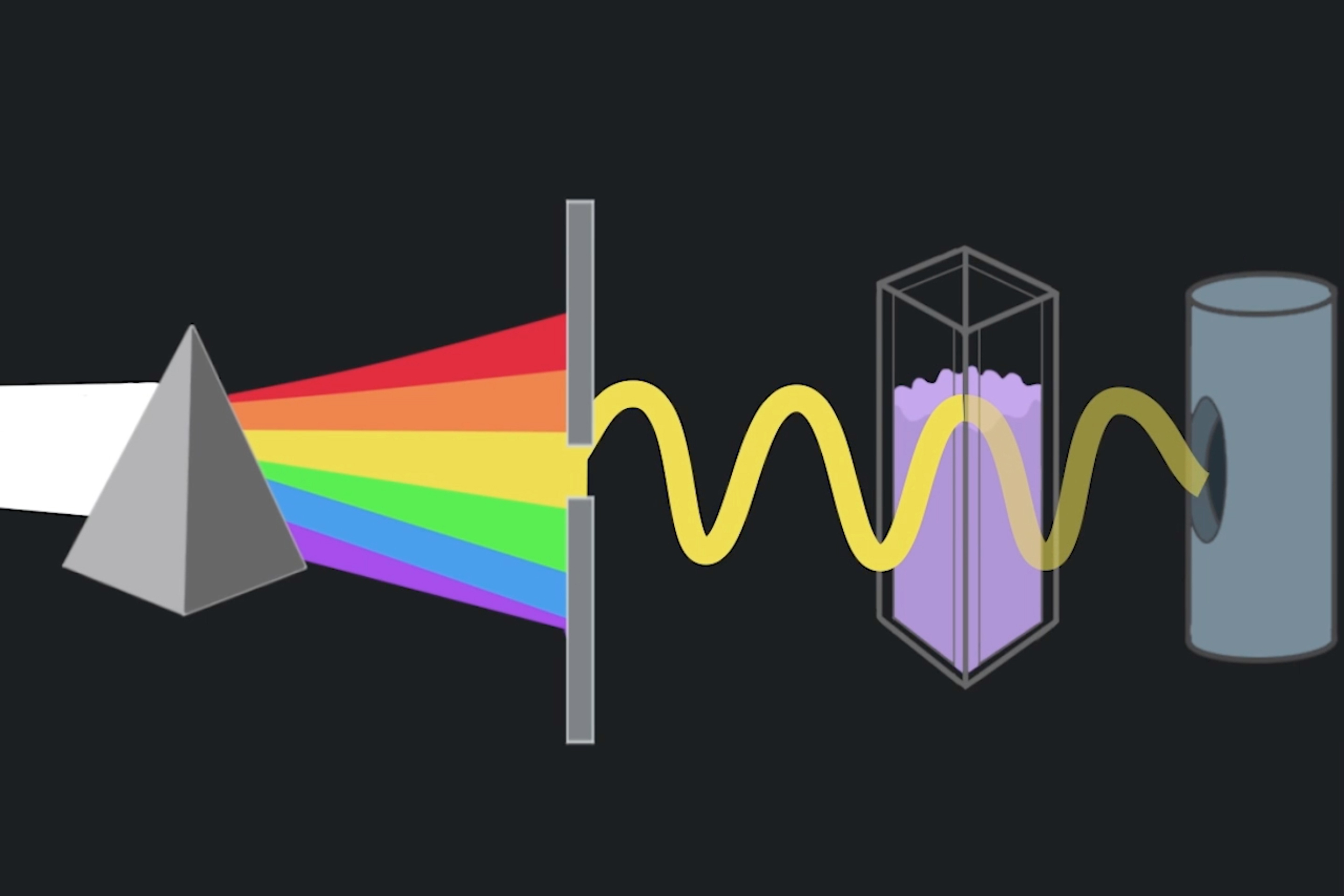

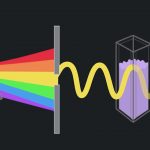

• “Spectrophotometry” demonstrates the science of measuring chemical absorption and reflection of light. Illustrations by Jessica Ortegon ’18 (CLAS)/(SFA), a double major in chemistry and art and art history. Animation by Alexandra Sailer ’19 (SFA), a DMD major.

Tamucci says part of determining which topics to address was the absence of existing animation on those subjects.

“There is nothing that explains joints in that way. There’s nothing that explains spectrophotometry, color absorption, and light absorption, either,” he says. “It’s cool to get things that you can’t find anywhere else.”

Lindemann and Paul called upon additional resources to help their students prepare for their classwork. They included a workshop led by Virge Kask ’84 (CLAS), UConn’s scientific illustrator; a lecture by Jean Givens, professor of art history, on the historical context of scientific visualization, dating from medieval times; and a presentation by Michael Astrachan ’87 (SFA), head of the Connecticut-based scientific animation firm XVIVO.

Such collaboration between creative artists and scientists is part of an expanding detente in the national debate over STEM versus arts education and the possibilities for combining the two, now known as STEAM – science, technology, engineering, arts, and math – which often holds up the example of Leonardo da Vinci, the Renaissance polymath known for both his painting and scientific inventions.

Paul says there were challenges for the students including learning how to communicate clearly with the scientists. “We all had to learn some new vocabulary as we navigated these interdisciplinary projects,” she says. “We’ve been able to work with Chris [Malinoski] and the TAs with our students on how to talk with clients. Chris has been great with me, stopping the critique of the actual animations to make notes about how students should be communicating with their clients.”

Adds Malinoski, the manager of the Biology 1100 laboratories, “It’s going both ways. The arts students are helping us immensely, and we’re contributing to their education learning to work with clients, and in this case, having that experience in the safety of a classroom. I think it’s great we’ve been able to collaborate in that way.”

“In the later classes of DMD there is a lot of collaboration, so we have to make sure we understand each other and have to look at it from the audience’s point of view,” says Henderson, who worked on the joints animation. “It kind of comes naturally to us. It’s a ‘symbiotic empathy’ thing.”

Her collaborator on the joints animation, Thuillier, says while working on the project she thought back to when she took BIOL 1107, asking herself: “What did I want to see when I was a student? What would have helped me learn the material better?”

Malinoski says today’s students are a generation of “visual learners,” and developing new animation, video, and other visual resources will continue.

“The heart and lungs are a complex system. To be able to show how these complexities are interconnected and working simultaneously is not something that you can do with any other traditionally available resources,” he says. “This solidifies it and allows more students to approach, understand, and appreciate the material being presented. I told the two arts professors when we first came into it that I understand they’re students, and if we don’t get workable animations at the end that’s OK, because there would still be education and a learning process that occurred for them and for us. The fact that we actually did get five usable animations I think is fantastic, and speaks to the quality of the education they’re receiving in the School of Fine Arts.”

Malinoski says that as other animations with narratives are developed, it may be possible to post them online as an open educational resource for other science faculty.