From the first Frontiersmen to the jet-setters of today’s global economy, we Americans consider ourselves a people who can, and do, get up and move to find better living conditions, better work, better partners, and better futures.

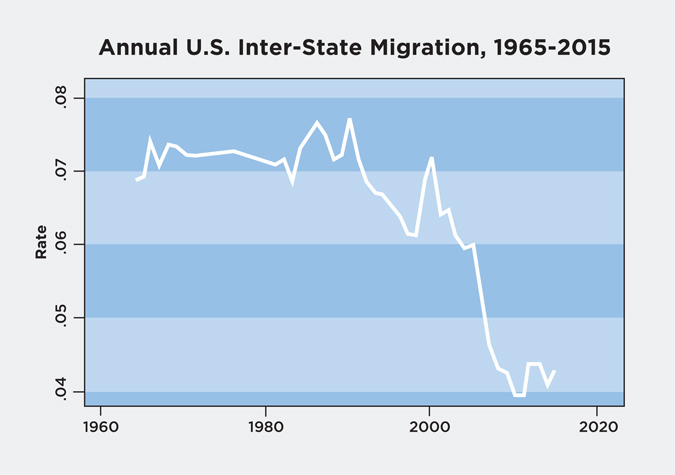

But despite this rhetoric, it turns out that Americans are moving far less than they used to, only about half as much as they moved 50 years ago.

And it has completely stymied demographers.

“I’ve been banging my head against a wall for almost a decade, trying to figure out why migration rates are declining like this,” says Thomas Cooke, professor of geography in the College of Liberal Arts and Sciences. “It seems so counterintuitive.”

Cooke spent the spring of 2015 in the Department of Demography at the University of Groningen in the Netherlands on a Fulbright fellowship, where he worked on just this problem. His research findings give the first direct evidence for one major factor contributing to this trend: divorce and child custody.

“Changes in family complexity, like divorce and child custody, make a big difference for migration,” he says.

Why not move?

Like many disciplines, Cooke says, demographers have a hard time agreeing on a simple definition of the very thing they study. But for his purposes, he says, moving or migration is defined as a person living in one state in one year, and another in the next.

In the last decade, several hypotheses have been proposed for the observed U.S. migration decline.

The American population is aging, as the baby boomers reach retirement and more people are living longer. So, perhaps older people move less, and that drives down the migration rate. But if you correct for the effect of age on likelihood of moving, Cooke says, it makes no difference.

Another idea is home ownership: maybe more people own homes, and so move less often. But home ownership rates have actually remained steady for about the last 20 years, says Cooke, so this can’t explain it.

The main explanation has been a poor economy, and that people simply can’t afford to move like they used to. But Cooke’s research has shown that despite surges and dips in the economy over the past 50 years, the rate of migration decline has remained constant.

So, what is driving this decline? Since U.S. divorce rates continue to increase, Cooke set out to determine if family complexity could help explain the trend.

Divorced, with children

Cooke’s current work stemmed from the idea that in the 21st century, families are becoming increasingly complex. More women are working, people often live with elderly parents or grandparents, and step-children and cousins often live under the same roof.

Cooke zeroed in on child custody following divorce. Using the University of Michigan’s Panel Study of Income Dynamics, which has gathered demographic data on a representative sample of Americans since 1968, he looked at the period of time immediately surrounding recorded divorces.

“If people were married in one year, and divorced the next, we looked at the effect that marriage dissolution had on where they lived after the divorce,” he explains.

His analysis confirmed that divorced people with children were even less likely to move than those without children. The findings support the idea that people’s lives are still linked, even if they divorce, Cooke says.

“People make decisions based on what their loved ones are doing, so the idea of linked lives is focused on people who care about each other,” he notes. “Migration research has always assumed that if you get divorced, you go your separate ways. Well, if a couple has children, they can’t go their separate ways.”

Although he calls his findings “unsurprising,” Cooke says they are the first direct evidence of divorce and child custody affecting migration in the U.S. Showing this trend empirically allows demographers to draw conclusions about why the trend exists.

Unlike the ’60s and ’70s, when state divorce proceedings usually awarded custody of children to the mother, joint custody is the norm today, Cooke says.

“Thirty years ago courts in general awarded custody to the mother,” he notes. “The father might move away, and see his child in the summer. Now fathers’ attitudes toward children have changed, and if they want anything to do with their children, they have to hold up their end of the custody.”

This idea is important for migration, because if a parent moves out of state, they lose custody. Thus, despite their divorce, former spouses tend more often to stay in the same state.

The new rootedness

Combined with other factors affecting migration, such as the ease of telecommuting and the use of technology to communicate with loved ones far away, these divorce factors could spell a new era of rootedness, says Cooke. And because migration is a learned behavior, he notes, future generations may move even less.

“If young people aren’t moving a lot now, they’re less likely to when they get older,” he says. “So I think migration rates will stay low or even continue to decline.”

Continued low migration could slow or reverse a trend of homogenization, the “melting pot” of cultures that has been a hallmark of the U.S. – a change, Cooke says, that could decrease intra-community diversity.

In his future work, he hopes to further investigate family complexity as a driver of migration decline, including focusing on other major milestones in people’s lives.

“In migration research we rely on the concept of the life course,” he says. “You graduate from high school, go to college, graduate college, get a job, get a promotion, get married, get divorced, et cetera. Migration studies hinge on the fact that life events drive migrations, because they change how you evaluate places.”