For a small state, Connecticut has a lot of coastline. When Hurricane Sandy blasted through in 2012, giving a taste of a future of flooding and extreme storms, the state took action. A coalition of regulators, municipalities, and UConn researchers designed a demonstration project in Bridgeport that works with the ecology and shoreline geography to protect critical energy infrastructure and residents in one of the state’s poorest, most vulnerable neighborhoods.

The proposal just won $54.3 million in January from the National Disaster Resilience Competition, held by the federal Department of Housing and Urban Development to distribute the last of the Hurricane Sandy recovery money.

“The underlying framework of Connecticut’s application is based upon enhancing resilience in communities increasingly at risk [as a result of climate change],” says Department of Energy and Environmental Protection (DEEP) Commissioner Robert Klee.

Klee notes that the project will take advantage of the state’s unique geography, and use it to support broader efforts to promote transit-oriented development. Because Interstate 95 and the Northeast rail corridor also run along the Connecticut coast, the economy of the entire New York-Boston region depends upon keeping the transportation lines in the state open and above water.

UConn’s Connecticut Institute for Resilience and Climate Adaptation (CIRCA) at Avery Point played a key role in the design of the winning project. Rebecca French, CIRCA’s director of community engagement, led a team that provided a comprehensive climate vulnerability assessment for the coast of New Haven and Fairfield counties, in partnership with state agency staff from State Agencies Fostering Resilience and the Yale Urban Ecology and Design Lab. Professor of marine sciences and executive director of CIRCA Jim O’Donnell advised on the flood risks that Connecticut will face from sea level rise and storm surge under current and future climate conditions, as the state developed Bridgeport pilot project.

“This is an important example of what can be accomplished when you combine the world-class, multidisciplinary researchers who are part of UConn’s centers of excellence, like CIRCA, and the extensive practical regulatory experience that exists in government agencies like DEEP,” says Jeff Seemann, UConn’s vice president for research. “This project will have a profound impact on the health and safety of Connecticut’s citizens and natural environment.”

CIRCA and DEEP saw the competition as an opportunity to test a strategy that capitalizes on the state’s geology. Connecticut is covered by a series of ridges and valleys that run north-south into Long Island Sound. A street by a town’s harbor might be just a foot or two above sea level, but rise steeply within just a few blocks to a 100-foot elevation or higher. Part of the federal award will support work like that of O’Donnell and UConn engineering professor Manos Anagnostou, who have been working on a model that can predict both coastal and inland flooding on a much finer, and more useful, scale than Federal Emergency Management Agency maps, which do not include the impacts of future sea level rise.

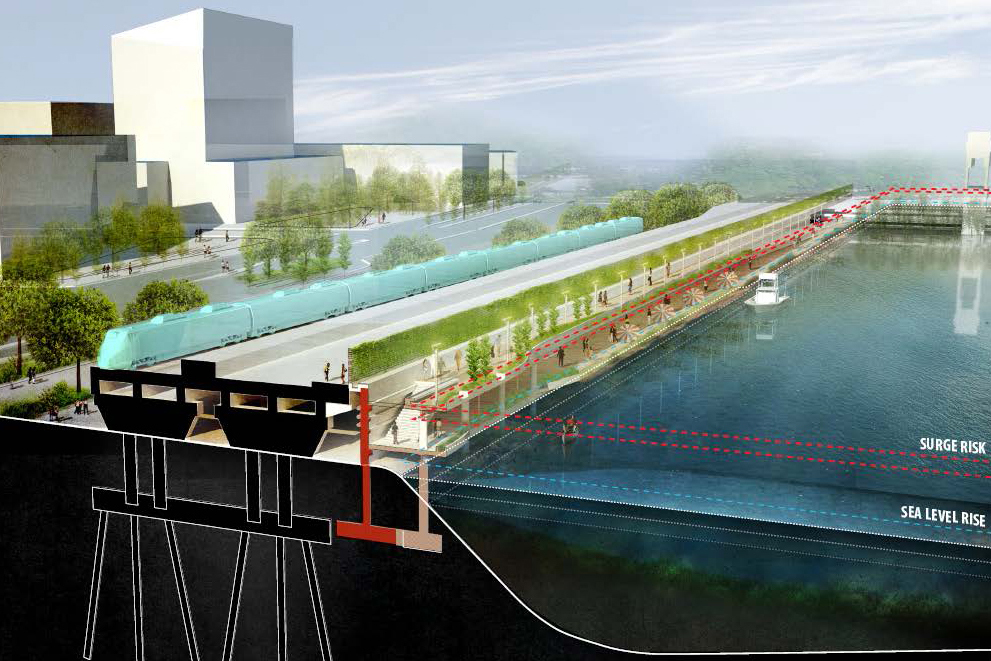

Much of Connecticut’s population lives and works near the coast. If key infrastructure connecting the high ground can be raised and protected, as proposed, the state might not suffer terribly from sea level rise. Such an ambitious project may eventually encompass even parts of the New York-New Haven-Boston railroad and Interstate 95. But Connecticut first needs to prove the concept.

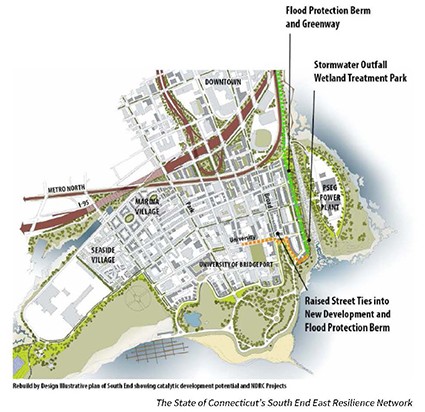

Bridgeport’s South End is the perfect place to test the strategy. A direct hit by a major storm right now could cut off the neighborhood from the rest of the city, stranding thousands of residents and taking out critical energy substations and generation plants. The neighborhood’s history stretches back to a pre-Civil War community of free black merchant marines and oystermen, but the community is currently cut off from the downtown by a disconnected street network, the sports stadium, and the University of Bridgeport.

Most of the federal money will go toward elevating University Avenue and constructing a greenway earthen berm to protect the community against storm surges. The raised street will also ensure access for rail, pedestrians, and bicyclists to and from the downtown, even during storms that previously would have flooded the road. Other streets will also be raised, creating a resilient corridor network that provides multimodal transportation options, while simultaneously protecting against floodwaters. The network would incorporate the natural ridge line that already exists along Park Avenue. Another part of the award allocates money to analyze opportunities for microgrids, cogeneration systems, and alternative energy sources, to limit disruptions during emergencies.

If successful, this project won’t end with Bridgeport. As part of the project design, regulators and researchers in CIRCA spoke with many coastal municipalities about critical infrastructure needs. If the Bridgeport project works well, the state may be able to implement a larger coastal resilience plan, investing in communities that are safe, resilient to climate change, and focused on sustainable solutions.