When does looking back tell you what’s ahead?

No, this is not the beginning of a clever children’s riddle. It’s an important question being asked by the emerging field of historical ecology.

In a paper appearing in the journal BioScience, UConn associate professor Matthew McKenzie and co-authors explore some of the issues raised by a growing field of study that began in the middle of the 20th century. Since then, burgeoning research – much of it influenced by the impact of climate change on the world’s ecosystems – has sought to evaluate not only the current state of various marine and terrestrial populations, but to track long-term changes by looking to the past.

In their BioScience paper, the authors point to a plant species previously considered to be an invasive weed in Florida which actually turned out to be a native species that provides crucial habitat to an endangered butterfly. This was proven through the use of historical data that challenged previously accepted scientific knowledge.

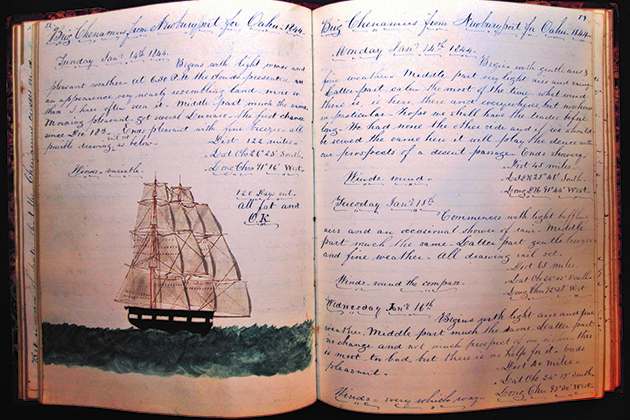

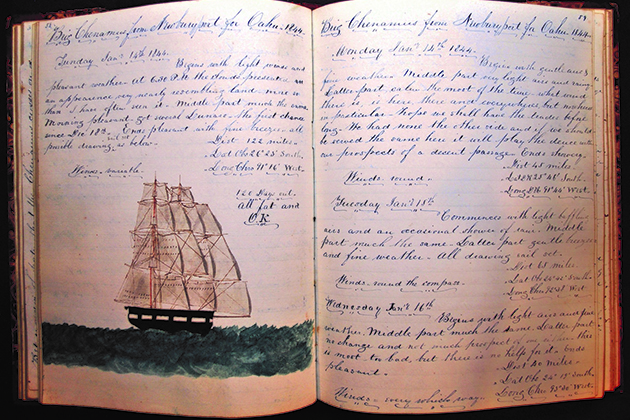

What makes historical ecology different from other forms of ecological research is that it relies on an integration of diverse sources, including physical evidence, archaeological remains, pollen records, genetic analysis, and other information more typical of the humanities and social sciences, says McKenzie. Historical ecology includes the use of records from ship’s logs, drawings, maps, diaries kept by adventurers, and oral histories that have been passed down through multiple generations.

Interpreting those records, he says, requires consideration of the context in which they were accumulated, the meaning of chronological gaps in data – and how to statistically correct for them – and how to use multiple lines of evidence while understanding the limitations of each.

“One of the fundamental tenets of historical ecology is that we know it’s not enough to merely take information at face value,” says McKenzie.

“Whether we’re looking at log books that recorded the number whales harvested in the North Atlantic during a certain time period, or reports of the number of bison killed on the Great Plains, or even the practices of indigenous peoples that were documented by early explorers, we know we have to factor in such things as inherent biases of observers, how well records have been preserved, and the cultural context in which observations have been recorded.”

We can’t really talk about rebuilding global marine resources effectively if we don’t have a good idea of how many there used to be. — Matthew McKenzie

McKenzie brings a broad perspective to the discussion. He is an associate professor of history, maritime studies, and American studies in the Department of History, teaching at the Avery Point campus. He also serves as Connecticut’s delegate to the New England Fisheries Management Council, a position that puts him squarely in the middle of policy decisions relative to the region’s multi-million dollar fishing industry.

His role on the Council requires him to vote on practices that govern such things as fishing areas, catch limits, minimum sizes, habitat protection, and even placing moratoria on the catch of specific species if they are nearing critical population levels. As a historian, he is able to bring historical resources to bear on his input.

“In a lot of places throughout the world, there aren’t records of any sort about marine resources in years past. But in other places, like the Atlantic basin and other parts of post-colonial Europe, there are historical records that can be very valuable if you know how to look at them,” says McKenzie. “We’re especially fortunate in New England, because the historical record is there, just waiting to be included in our decision-making processes.”

And while historical sources have sometimes invited criticism, particularly when the results contradict current assumptions, McKenzie believes these sources are essential for both ecological and conservation efforts.

“The idea is that we can’t really talk about rebuilding global marine resources effectively if we don’t have a good idea of how many there used to be,” McKenzie says. “Historical ecology helps us do that.”