Dr. Se-Jin Lee first discovered myostatin in 1997, a protein that is part of a system of checks and balances that limits human muscle growth. That discovery launched an extensive effort in the pharmaceutical community to develop myostatin inhibitors to treat muscle diseases.

Despite numerous drugs that were taken into clinical trials for a wide range of conditions characterized by muscle loss and weakness, the results of those trials were initially disappointing in terms of improving clinical outcome — until now.

Three companies – Scholar Rock, Biohaven, and Roche – have been testing myostatin inhibitors in phase 3 trials in patients with spinal muscular atrophy (SMA), a rare neuromuscular disease with devastating consequences. Based on the results of these trials, one of these companies, Scholar Rock, is now seeking FDA approval for their myostatin inhibitor, which is based on a fundamental mechanism discovered by Lee by which myostatin is regulated.

“I could not be more excited to see this effort now on the doorstep of finally reaching fruition,” says Lee, Presidential Distinguished Professor at UConn School of Medicine and professor at The Jackson Laboratory who consults for Biohaven.

With the potential use of myostatin inhibitors in patients with SMA on the horizon, this is now accelerating into efforts to target myostatin for obesity.

This effort has its origin over two decades ago with studies that Lee did showing that knocking out myostatin not only increased muscle growth but also reduced body fat. Fast forward decades later, his discovery of the power of the myostatin pathway is fueling new promising obesity drug development and clinical trial testing.

As spotlighted in February’s Nature Reviews Drug Discovery, in which Lee’s myostatin discovery and ensuing investigations over the next three decades are featured, there are clinical trials of at least 10 drugs either underway or soon launching that target myostatin and the related protein activin A or their receptors in varied ways or with a combination of drugs, with even more clinical trials rapidly evolving.

“Many major pharmaceutical companies as well as biotech companies are developing drugs capable of blocking this signaling pathway, as these drugs have the potential to simultaneously increase muscle mass and reduce body fat,” says Lee. “The potential indications for myostatin drug discovery are going to explode in the coming years.”

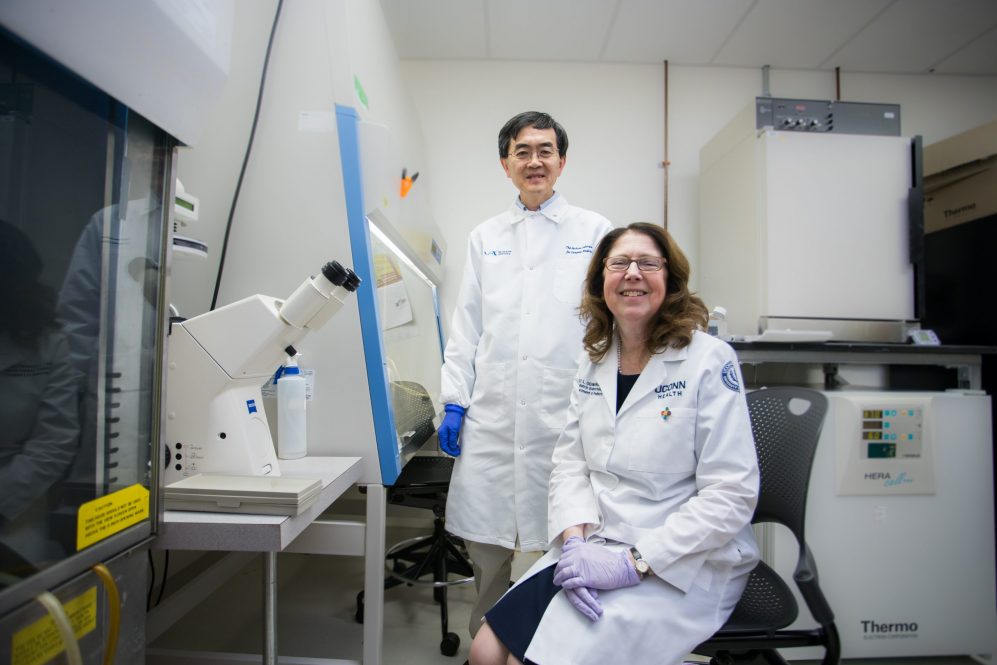

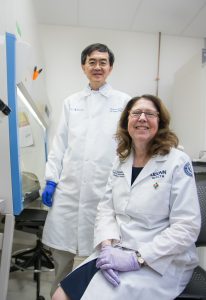

At UConn School of Medicine Lee and his wife, Dr. Emily Germain-Lee, a physician-scientist and pediatric endocrinologist who is a professor of Pediatrics at the UConn School of Medicine and Head of Academic Affairs and Research for Endocrinology at Connecticut Children’s, are further co-investigating the underlying biologics of obesity and the potential for creating future healthier, weight loss drug options.

Their study explorations are identifying the key tissues responsible for the regulation of obesity by myostatin and activin A and developing the most effective strategies for modulating the molecules’ signaling pathways. In 2019, they even sent mice to the International Space Station, where studies showed that blocking these molecules prevented bone and muscle loss in the mice, even in the setting of microgravity in which dramatic decreases in both bone and muscle mass typically occur. Now, they are building on their out-of-this-world research efforts to help tackle the obesity epidemic.

Why myostatin?

The renewed interest in targeting myostatin for obesity coincides with the enormous success of GLP-1 (glucagon-like peptide-1) obesity drugs. As effective as these drugs are in causing weight loss, one concern has been that up to 40% of that weight loss is not due to fat loss but rather due to muscle loss. Moreover, when patients discontinue these drugs, the weight that they regain is predominantly fat rather than muscle.

As a result, there is an enormous interest in developing myostatin inhibitors to preserve muscle mass in patients receiving GLP-1 drugs. The UConn team’s research has already shown in the lab in mouse models that myostatin inhibitors cause fat loss, so they are currently examining the possibility of developing them as future obesity drugs that can also preserve muscle. The myostatin drugs work by helping muscles grow while in turn reducing fat as the muscles consume more energy.

The UConn team’s goal is to try to find a more practical and potent solution and to offer obese patients a healthier muscle-sparing weight loss drug option with fewer side effects. Also, they believe the new-age myostatin drugs might work best if given alongside the injectable GLP-1 obesity drugs. The hope is the combination would allow for a reduction in GLP-1 doses leading to fewer untoward consequences.

“The challenge of the obesity epidemic is widespread and one that even pediatricians face constantly,” adds Germain-Lee, who frequently sees first-hand in children the significant morbidity from obesity. She explains that “effective treatments having the least detrimental impact on the musculoskeletal system are crucial.” As a physician-scientist with a long-term focus on both endocrine and rare disorders, particularly a rare condition in which obesity is unable to be treated by dietary measures or current therapeutics, she is very excited about the benefits that myostatin inhibitors could provide.

“The challenge of the obesity epidemic is widespread and one that even pediatricians face constantly,” adds Germain-Lee, who frequently sees first-hand in children the significant morbidity from obesity. She explains that “effective treatments having the least detrimental impact on the musculoskeletal system are crucial.” As a physician-scientist with a long-term focus on both endocrine and rare disorders, particularly a rare condition in which obesity is unable to be treated by dietary measures or current therapeutics, she is very excited about the benefits that myostatin inhibitors could provide.

In her role as director of the Scientific Center for Rare Disease at Connecticut Children’s Research Institute, Germain-Lee adds, “in addition to helping to tackle the global problem of obesity, the potential for seeing infants and children with SMA having their lives transformed by myostatin inhibitors is truly amazing.”

February 28 marks National Rare Disease Day.