When Kiedra Taylor, an English Ph.D. candidate, was deciding on her dissertation topic, she began searching archives for literature written by Black girls but found the material hard to access.

Taylor was interested in understanding what it meant to be a Black girl in “very trying racist times,” but struggled to find work by Black girls because, she says, finding archived materials requires careful and specific searches.

“I just wasn’t finding anything that would allow me to write a whole dissertation on it,” she said.

At the same time, she was also working as a graduate assistant with the Connecticut Writing Project (CWP), a professional development network that supports teachers of writing at all grade levels. There, she noticed that some of the submissions she read appeared to be written by Black children based on the experiences described.

Taylor thought it would “be cool if we had a space for children of color to just let go because I could tell in the pieces that they were holding back.”

With encouragement and guidance from Jason Courtmanche, associate professor in residence of English and director of CWP, Taylor launched “Write On, Black Girl,” an annual literary magazine where Black girls in Connecticut can submit and share their writing.

Since its inception, the magazine has published the work of dozens of girls in grades K-12 and at the university level, showcasing various writing styles, from poetry to personal essays.

“I noticed that in the contemporary discourse about Black girls and literacy, and Black girls and social justice, there are a lot of folks talking about Black girls, but no one actually talking to Black girls,” says Taylor, whose major advisor, Professor of English and Associate Dean for Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion, Collaborative Programs, and Faculty Development Kate Capshaw, has written on Black children’s literature. “That was very important for me.”

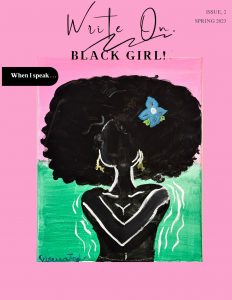

The magazine, currently working on its third edition, has recently partnered with Porch Water Press, a publisher run by queer Black women and based in New Jersey and New York.

Taylor says the collaboration will not only provide the magazine with the backing to improve its production quality but could also be a door to help participants consider publishing their work independently.

The magazine’s first two issues have been released digitally. Taylor said before collaborating with Porch Water Press, she was able to produce the magazine with funds and resources from CWP, the College of Liberal Arts and Sciences, the Africana Studies Institute, and an independent donor through The Dodd Center for Human Rights.

Kenia Hale, co-founder of Porch Water Press, says the third edition, which will be released before the end of this year, will be a hard copy. The publishing house also plans to print the second issue.

While there are many outlets for young Black female-identifying individuals to have their work published, Taylor wanted Write On, Black Girl to be a nurturing space where they felt empowered to share their experiences and could feel heard. The magazine features a variety of genres and include themes such as “Dear Black girl” or “Black girl, you are loved.”

“I read every piece personally,” Taylor says. “I’m looking for how this work allows our audience to get a peek into what it’s like to be a Black girl or gender non-conforming person from this writer’s perspective.”

The collaboration between Porch Water Press and Write On, Black Girl, began after Taylor, Hale, and co-founder Isa Escobar were part of the same cohort of The Race and Gender Equity (RAGE) Lab at Rutgers University. The RAGE Lab is a three-day research and training incubator that works to support Black feminist research on the social thriving of Black women and girls and makes that research accessible to broad public audiences.

“I see a beautiful opportunity to get that [writing] onto paper here,” Escobar says.

Escobar says Porch Water Press was co-founded on the notion of creating a platform for underrepresented individuals who may not have access or resources to have their work published elsewhere.

For Hale, seeing young girls have a chance to produce their work is fulfilling and reminds her of how she loved to read and write as a child.

“I’ve always loved Black feminist literature and Black queer feminist literature,” Hale says. “Growing up I was really into books where I found people whose lives reflected my own. “It was in the writing of Barbara Smith, and Audre Lorde, who founded Kitchen Table Press. They essentially showed me not only could I survive as a Black queer woman writer, but I could write and create worlds where other Black women and other people in general could see themselves in the future too.”

Taylor approached the pair because of the similarities in their objectives and all three say they’re excited to continue to grow Write On, Black Girl, and have it become a physical book that the participants and others can actually hold and read.

“For them to see their work collected in this artifact means something different,” Taylor says. “This is a book they can’t ban; they are saying what they have to say without fear of censorship.”

Danicia Brown ’23 (CLAS) helped Taylor put out the second issue. As an editorial assistant, Brown sent out newsletters, worked on social media, and helped organize a writing retreat for young Black girls to come to UConn and develop their writing skills.

Write On, Black Girl has hosted four writing retreats for young Black girls in Connecticut. Two of the retreats were hosted at UConn, while two were hosted at Central Connecticut State University. Taylor said each of the retreats accommodated 20 young people and featured talks from established authors such as Marilyn Nelson, campus tours, and a chance to learn from professionals affiliated with each university.

Brown, who majored in English, was able to earn internship credits for their work and says the opportunity allowed them to work on something they were passionate about.

“I’m a Black female writer myself,” Brown says. “I believe we don’t get as many publishing opportunities as [other writers]. The majority of [Black female] writers are very often overlooked, and I find that Black female writers are usually the best. I wanted to create this opportunity for young Black women to be published for the first time and have their work displayed for everyone.”

After graduating, Brown was awarded a Fulbright scholarship to teach English in Germany. Now in their second-year teaching in Düsseldorf, and inspired by their work on Write On, Black Girl, Brown plans to start a writing or reading group for Black girls at their current school.

“I just want them to write and to realize their worth,” Brown says.