For 10 weeks this summer, Gianna Socci worked hard for a sole purpose.

As if her gift was the plunder of information from the stacks of libraries in southwestern Connecticut, piece by piece she stitched together thoughts, contentions, and beliefs, her own cheeks pale with study, as she infused life into the inanimate body that’s become her very own creation.

“I’d never taken on a beast this size before,” Socci ’25 (CLAS) says. “I would get very stressed out that I wasn’t going to be able to finish this. I wasn’t going to be able to write something that made sense. I wasn’t going to be able to bring this all together and I feared I bit off more than I could chew.”

Clinging to the hope the next day or the next would bring success, Socci labored to coax to life the 62 pages that have become her greatest academic triumph to date: “Monstrosity on Trial: Claiming Legal Personhood for Frankenstein’s Monster.”

This is a project Socci conceived nearly two years ago, when as a sophomore she sought to convert her Introduction to Literary Studies course into an honors credit, which requires a larger research project, namely a more in-depth look at one of the books read that semester.

“I had worked hard for nearly two years, for the sole purpose of infusing life into an inanimate body. For this I had deprived myself of rest and health.” – Victor Frankenstein in describing his work in Mary Shelley’s novel “Frankenstein”

As an English and political science double major who expects one day to take up the study of law, Socci heeded the advice of associate professor Dwight Codr and looked at Mary Shelley’s 1818 novel “Frankenstein” through a legal lens.

What started as an honors conversion paper became a much larger Summer Undergraduate Research Fund (SURF) grant proposal, replete with a reading plan of an admittedly ambitious 37 works, including dense legal case studies, she says. The funding allowed her the space in June, July, and August to focus on her work, without worrying about money.

“Research in the humanities is very rare to begin with,” she says, “and I don’t think a lot of people understand what it entails. When you’re a STEM major, you can lay out lab steps, you can show people graphs, diagrams, and lab methods. It’s very quantitative, whereas humanities research is reading, taking notes, thinking, and writing.”

It’s nonetheless important, she argues.

Not the Frankenstein you might imagine

One of the first things Socci says she was shocked to learn when reading “Frankenstein” the first time two years ago was that the character of Frankenstein, contrary to popular belief, is not the monster depicted in the story.

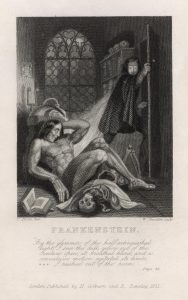

Victor Frankenstein is the young doctor who brings to life an 8-foot-tall monster – born of inanimate body parts he stole from graves and mortuaries. Most contemporary depictions of Frankenstein wrongly show him as the flat-headed, green, almost zombie-like monster with bolts in his neck.

That is, in fact, Frankenstein’s “creature,” who in Shelley’s book is never given a name, referred to only by such descriptors as “devil,” “thing,” and “ogre.”

“The other thing that struck me – and this might just be my poli-sci brain at work – was that she included three legal proceedings in the novel, three specific examples of courtroom trials, and that’s not something that’s talked about. You typically think of ‘Frankenstein’ as a very science-fiction text,” Socci says.

Those trials, in which the defendants aren’t in fact guilty of the crimes they’re accused, got Socci thinking about how the law weaves itself through the novel and found herself wondering: What if Frankenstein’s monster was granted legal personhood and able to stand trial for his wrongdoings?

Before she could answer, she needed to tackle the idea of what it means to be a legal person and how that idea has been used over time. She turned to legal theory, philosophy, history, and Shelley’s text for answers.

“Legal personhood is a status, which means someone has rights and privileges but can also be held responsible for their actions,” she explains. “It’s twofold and it’s been expanded and contracted over time to include and exclude so many different things and people.

“Slaves had a very limited form of personhood. Women had a very limited form of personhood. Animals at one time were granted legal personhood and could be put on trial, which is completely absurd,” she continues. “The law is flexible and almost subject to the politics of the time. That reminded me, as a citizen, as a woman in contemporary times, the importance of paying attention to that.”

“My cheek had grown pale with study, and my person had become emaciated with confinement. Sometimes, on the very brink of certainty, I failed; yet still I clung to the hope which the next day or the next hour might realise.” – Victor Frankenstein in describing his work in Mary Shelley’s novel “Frankenstein”

Things like cognition and competency are used in helping distinguish personhood, even intent and mental capacity. And when Socci looked to the novel for these characteristics as they relate to the monster, her conclusion was clear.

“He is a completely cognizant being who acted with intent,” she says. “He was very aware of what he was doing. He could express himself. He was extremely human in every way but his physical appearance. Violence is never the answer, and his reasoning for violence is flawed, but it’s reasoning, nonetheless. He’s angry, and he’s acting in a very methodical way. He is totally eligible to stand trial.”

‘Abstractions rule our lives’

Socci says that at the outset of her research, when telling people how she was spending her summer, she started to wonder why she was even bothering. Arguing about whether Frankenstein’s monster could be held criminally liable for his actions is an exercise in the abstract.

Except it is relevant, she was reminded.

In an interview with an Australian professor who’d written about personhood, she asked why any of this mattered.

“He said abstractions rule our lives. These legal definitions, these philosophical foundations are what govern our whole being,” she says. “We don’t really think of ourselves in legal terms that often, so it can seem unimportant. But it’s how we have the right to vote. It’s how we have the right to express ourselves. It’s how we’re seen by the government.”

Suddenly, what once was hypothetical was much more concrete.

The European Union this year adopted the AI Act, Socci notes, which, in part, rates various artificial intelligence technologies on their risk level – high-risk AI is more autonomous and can operate with minimal human intervention, for example. The AI Act seeks to regulate high-risk artificial intelligence.

Consider Hollywood movies like “Avengers: Age of Ultron,” in which the artificial life form, Ultron, seeks to destroy. Technology advances rapidly and might not be that far off from the movies.

“If an AI is a sentient being and it decides to act out on its own will and is harming someone, we’re going to have to start thinking about liability,” Socci says. “My theory holds the monster accountable and therefore would hold the AI accountable. Then, if you can hold the AI accountable, shouldn’t they also have rights and be able to vote if we’re talking about the dual edge of legal personhood.”

Socci surmises that humans will be unlikely to put robots and technology on the same level as themselves, but that conversation may very well need to be had, which means the hypothetical turns real.

In the U.S. Supreme Court’s 2010 Citizens United decision that gave corporations the right to make political donations, the reasoning, Socci says, is that businesses have a right to free speech, in this case through their dollar, and that can’t be infringed upon.

“Legal personhood is not the reason for that decision, but if you go through the legal text, the chief justice uses very personifying language when talking about corporations, saying they can bring a good perspective into the democratic dialogue. And suddenly, corporations can talk like people. This tendency to personify the inanimate is where we see legal personhood bleeding into our contemporary scheme,” she says.

A story about injustice

In a planned career as a lawyer, Socci says she’ll take many of the things she’s learned from this project and apply them to work with abused and neglected children, who oftentimes need an advocate to protect their rights.

And in a way, children are a little like the monster – seeking to belong, looking to be molded, hungry for learning. Victor Frankenstein’s rejection of the monster, in the same way a parent might reject a child, results in lifelong ramifications.

“You might feel sad for the monster because all he really wants is to be part of the human community,” Socci says. “There’s a whole segment of the book in which he is watching the DeLacey family from far away in his hovel. He realizes they’re poor, so he starts leaving food on their steps. He shovels their driveway. He helps them out despite the fact he’s been rejected by his creator.”

Socci says that while there are dozens of ways one could analyze the story, for her, “Frankenstein” boils down to a tale of injustice.

“We hear the word ‘monster,’ and we think ‘beast.’ We’re scared. Something’s uncivilized. Something is rowdy. Something is dangerous. But the monster, in the beginning, is anything but that,” she says. “He’s a very rational individual who just wants to be close to someone. I think Shelley is asking us to think about the definitions we’ve applied to others.”

And that interpretation may become part three of “Monstrosity on Trial” – the honors conversion project turned SURF grant award, yet-to-become English honors thesis.

“I don’t think there’s going to be another time in my life, unless I become an author, when I’ll have dedicated hours for researching and writing, not worrying about the income I’m missing out on,” Socci says of the SURF grant. “It was honestly a privilege to have this experience.”