Spring, summer, and fall in Connecticut come with the standard advice on preventing tick bites: Avoid areas where ticks are active when possible, wear long sleeves and pants when reasonable, use insect repellent with DEET (more than 20% DEET lasts at least six hours), and check your body for ticks regularly.

Ticks in Connecticut can carry organisms that cause Lyme disease and, less commonly, anaplasmosis, babesiosis, ehrlichiosis, and in very rare cases, Rocky Mountain spotted fever. Still, a lot needs to happen before a tick bite can lead to illness, as Dr. Henry M. Feder Jr., professor of family medicine in the UConn School of Medicine, explains.

What do the deer and lone star ticks carry?

The Connecticut Agricultural Experiment Station (CAES) gets a few thousand ticks each year for analysis. The CAES tests deer (black-legged) ticks for three pathogens: Borrelia burgdorferi (the bacterial culprit of Lyme disease), Anaplasma phagocytophilium (the bacterial culprit of anaplasmosis), and Babesia microti (the parasitic culprit of babesiosis). Plus they map the areas of Connecticut where the infected ticks are found.

What’s changed over the last decade is, the lone star tick has invaded Connecticut. About 6% of the ticks sent to the CAES are lone star ticks. Lone star ticks carry Ehrlichia chaffeensis, the pathogen that causes ehrlichiosis.

The CAES gets more than 3,000 deer ticks to analyze yearly, and slightly more than 40% of the deer ticks contain, at least, one pathogen (Borrelia burgdorferi, Anaplasma phagocytophilium, and/or Babesia microti). The good news is, a tick bite from an infected tick usually does not result in clinical disease. The risk of developing Lyme disease after a Borrelia burgdorferi-infected deer tick bite is about 10%. The risk of developing anaplasmosis or babesiosis after being bitten by an infected tick are unknown, likely less than 10%.

What are some factors that could put us at risk for tick-borne illness?

Living in an area where there are a lot of ticks is a risk. The ticks mate on deer, thus more deer means more ticks. The percentage of infected ticks is another risk. Deer ticks acquire Borrelia burgdorferi when they feed on Borrelia burgdorferi-infected mice. For example, in Elizabeth Park in Hartford, they have deer ticks, but these ticks are not infected because the local mice do not carry Borrelia burgdorferi. If you go to the Old Lyme, East Lyme, Haddam, and Colchester areas, in that belt, a lot of the mice are infected, making a higher risk of getting Lyme disease after a tick bite. Deer ticks in Simsbury or West Hartford or Farmington are less likely to be Borrelia burgdorferi-infected. Deer tick bites in these areas are less likely to result in Lyme disease than bites in Old Lyme, East Lyme, Haddam, and Colchester.

In a way, finding a tick on you is good, in that it means it hasn’t finished feeding yet. Explain that?

To transmit Lyme disease, an infected deer tick has to be attached for at least 36 hours, usually more than 48 hours. It has to attach, feed, and engorge to give you disease. People who do daily tick checks and are good at finding ticks (on themselves and/or their children) can decrease the risk of getting Lyme disease or another tick-borne illness.

But even if a tick is on you for 48 hours and has fully engorged, that still doesn’t guarantee you’re getting sick?

A lot of times they get fully engorged and fall off and you never know it happened. One thing with Lyme, if you call a physician, and you just say, “I had a tick on me, it’s probably been on two days,” a great number of physicians will give you what’s called a double dose of doxycycline (two 100 mg capsules), which is very good at preventing an infection with Lyme disease. There are no studies looking at the prevention of anaplasmosis and babesiosis following a tick bite.

Lyme disease is far more common in Connecticut (and the United States) than anaplasmosis and or babesiosis. Each year in Connecticut about 2,200 cases of Lyme disease are reported, versus 70 cases of anaplasmosis, versus 200 cases of babesiosis. To put this in perspective, there are many, many thousands of Connecticut residents getting tick bites.

Lyme disease usually presents with a distinctive circular red rash, with or without fever. Anaplasmosis and babesiosis usually present with fever, chills, headache, malaise, joint pains, and no rash. Ehrlichiosis and Rocky Mountain spotted fever (Rickettsia rickettsii, from the dog tick) are very rare in Connecticut.

What about concerns of these bacteria developing resistance to antibiotics?

Two doxycycline 100 mg capsules can be used to prevent Lyme disease after a tick bite (if given within 72 hours of the bite). Borrelia burgdorferi has never been shown to develop resistance to doxycycline. Thus, doxycycline can be used multiple times after tick bites without danger of resistance. Also, doxycycline or amoxicillin are used to treat Lyme disease (with courses of 10 to 28 days) and resistance after even multiple courses of therapy have not been reported.

What about “chronic Lyme disease”? You consider that to be “misinformation.” Why is that?

The term “chronic Lyme disease” suggests persistent Lyme infection following a standard course of antibiotic therapy. Borrelia burgdorferi, the bacteria responsible for Lyme disease, has never been scientifically shown to survive doxycycline or amoxicillin therapy. Theories of how Borrelia burgdorferi escape antibiotic therapy include: (1) it hides in a place inaccessible to antibiotics, (2) it makes a biofilm that protects it, (3) it becomes antibiotic resistant, (4) it needs higher doses and/or longer courses of antibiotics. None of these theories have been scientifically demonstrated.

Why then do some people after Lyme disease do so poorly?

The initial episode of Lyme disease (rash, facial nerve palsy, arthritis) may be associated with nonspecific symptoms of fever, headache, brain fog, joint pains, and/or severe fatigue. With antibiotic therapy the rash and fever resolve within 24 to 48 hours; however, the nonspecific symptoms like headache, brain fog, joint pains, and/or severe fatigue may persist for weeks or months. The cause(s) of the nonspecific symptoms after infection is an area of intense research. Nonspecific debilitating symptoms can follow Lyme disease, mononucleosis (initially called “chronic mono”), and most recently “long COVID.” It has been clearly shown that for Lyme, the Borrelia burgdorferi infection is gone; for mono, the Epstein-Barr virus is gone; and for COVID, the COVID-19 virus is gone. These post-infectious syndromes mimic chronic fatigue syndrome. With acute illness our bodies make cytokines, which make one feel miserable. Possibly this cytokine production (or something like it) continues after the initial infection is resolved. Thus, chronically treating the initial illness as though it were still present is not helpful (except for placebo effect of any drug therapy).

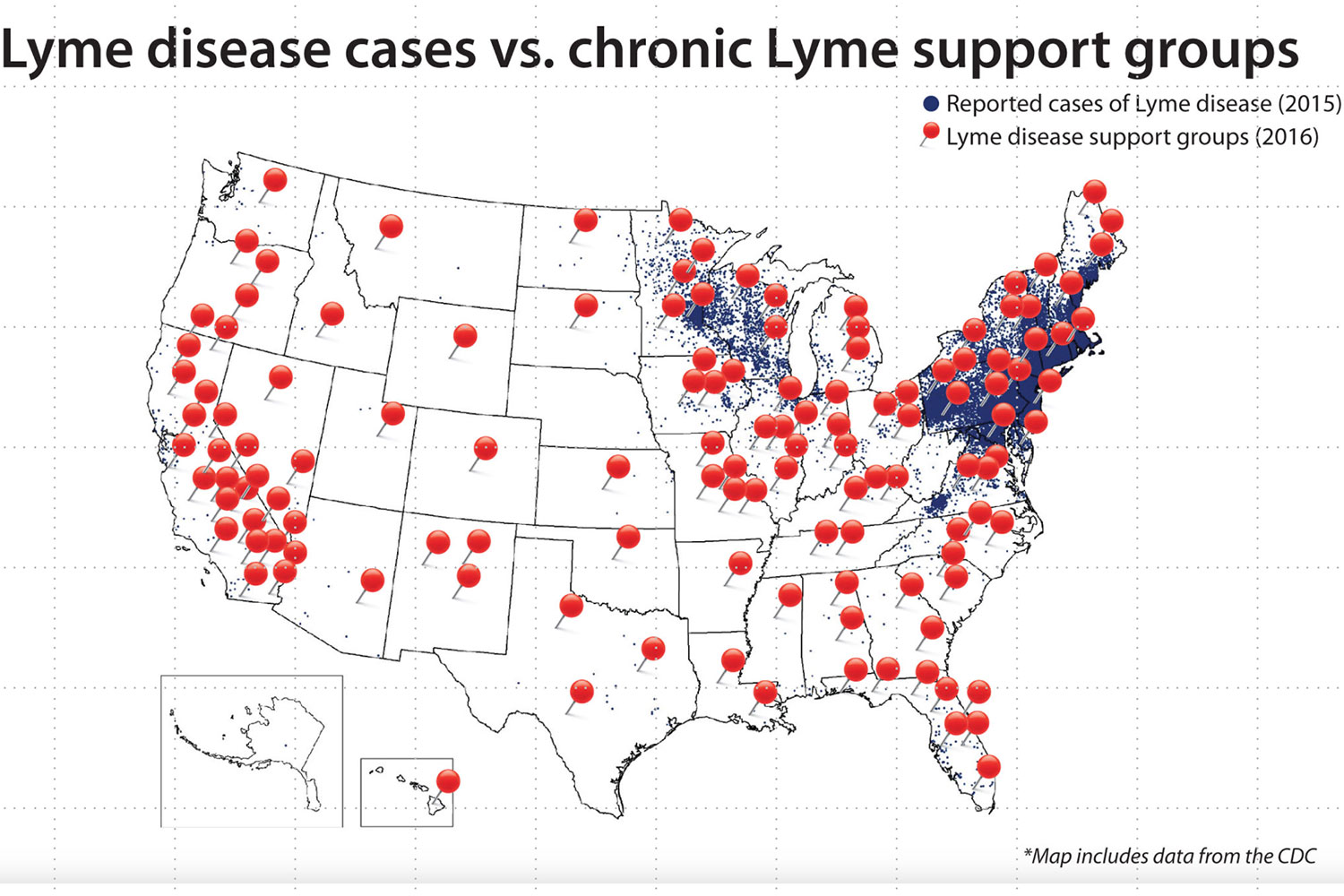

Tales of “chronic Lyme disease” populate the news, popular magazines, and especially the internet. Many people know personally of loved one, a friend, or a friend of a friend suffering from “chronic Lyme disease.” Many of these people are cared for by a network of physicians who believe Lyme disease explains symptoms that mainstream doctors can’t explain. What is interesting is this network of physicians practice throughout the United States, even in areas where Lyme disease is not present.

There’s a map published by the group LymeScience, using CDC data, of the geographic location of Lyme support groups, which does not match up where Lyme disease is endemic – the Northeast and Minnesota/Wisconsin. Some people after Lyme disease have debilitating symptoms (called “post-Lyme symptoms” not “chronic Lyme disease”) parallel to “long COVID.” However, using the map as a reference, it is highly likely that many of those diagnosed with “chronic Lyme disease” never had Lyme disease.

Most people who develop Lyme disease or another tick-borne illness never noticed a tick bite because a deer tick is the size of a poppy seed, and an attached tick usually causes no symptoms. Being careful and doing tick checks after outdoor exposures and reduces the risk of developing a tick-borne illness. Most tick-borne infections have clear signs and symptoms and are treatable. The concept that a tick bite may lead to persistent and untreatable “chronic Lyme disease” is misinformation.