One of the most important, and most volatile, moments in the history of the University of Connecticut is being remembered in an exhibition curated by the Archives & Special Collections in the Richard Schimmelpfeng Gallery located at The Dodd Center for Human Rights.

“Please Respond Personally: Commemorating the 1974 Black Student Sit-in” can be viewed through July 19; an opening reception and open house will be held Thursday, March 28, from 3 to 5 p.m. in the John P. McDonald Reading Room.

The exhibition remembers action taken by Black UConn students in April 1974 as part of a campaign to demand representation and resources for students of color. Eventually, the students held a sit-in at the Wilbur Cross building – which in 1974 was the University’s main library – on April 22 of that year, which resulted in arrests the next morning for more than 200 students who would not leave the building.

“This is a time just after the United States withdrew from Vietnam, and there is a major transition in our country to a period of student activism and unrest from the U.S. role in the war to how minority students are represented on college campuses, particularly at UConn,” says Graham Stinnett, a UConn archivist who curated the exhibit. “The Black students had demands for things like better meeting spaces and more books in the library about Black history and culture.”

Stinnett started working on this project in 2017 as the archives began to digitize photographs of the student unrest for the 50th anniversary of UConn’s H. Fred Simons African-American Cultural Center, which took place in 2018.

The take-over of the Wilbur Cross Library, which became the Wilbur Cross Building in 1978 when the Homer Babbidge Library opened, came after a number of peaceful protests and demands from Black students, which were led by the Organization of African American Students.

One of the most powerful parts of the display is the back wall, where copies of letters from Black students that were presented to President Glenn Ferguson are shown. The typed form letters are identical, except students signed their own and many wrote personal messages. Students presented the letters to Ferguson one morning when he arrived at his office, and they ended with the phrase – “Please Respond Personally” – which gave the exhibition its name.

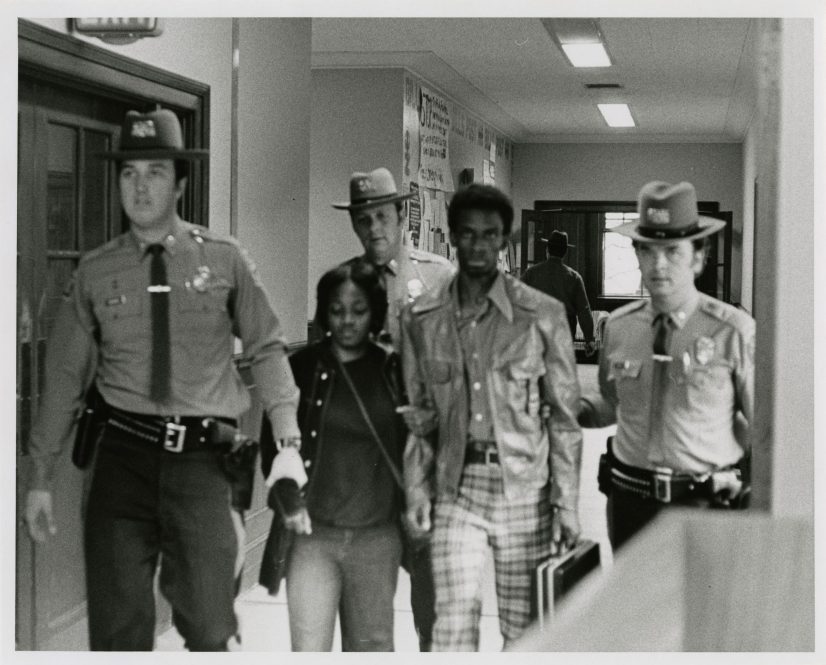

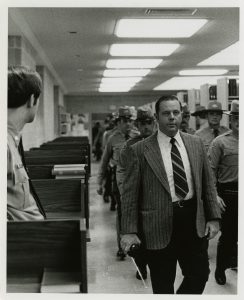

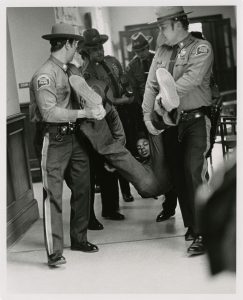

The exhibition also has stark photos of Black students being arrested and removed from the Wilbur Cross Library after they refused to leave when the building closed at midnight.

“These photographs are a very curious part of our student unrest collection, as there was basically no provenance of where they came from at first,” says Stinnett. “They are from the perspective of inside the library when the state police started removing the students, but they are not journalistic and have a more surveillance look to them.”

Stinnett believes he has identified the photographer, who was under contract for the Connecticut Chronicle, which was a faculty and staff newspaper at the time.

“He must have been called in the middle of the night and told what was going on,” says Stinnett. “They wanted to document these students and know who they were.”

A key contact for Stinnett in creating the exhibition was when he identified Rodney Bass ’75 (CLAS) ’76 MA as one of the students being arrested. Bass was co-chairman of the Organization of African American Students, a member of the men’s basketball team, and involved in Black Voices of Freedom choir and other student activities.

Bass, who later went on to become a school principal in his native Stamford, read a statement that explained he and his fellow Black students would not leave the library when it closed at midnight. The students stayed there until 6 a.m. the next day, when police arrived. Charges of criminal trespass were levied against 219 students.

Another protest at the library occurred later that same day to support the Black students, which was conducted largely by white faculty and students.

“I am glad that the 1974 sit-in is not being ignored, and that students who are here now have the opportunity to learn and persevere to move things even more forward,” says Bass. Bass was a recent guest on d’Archive – the UConn Archives’ podcast.

The exhibition also deals with the controversy around UConn’s Department of Anthropology being split in two, and the protest of that move started by anthropology graduate students. One part of the department was cultural anthropology, while the other part dealt with bio-behavior research, which included laboratory work to illustrate there are inherent traits based on a person’s genes, a topic that had a holdover from race-science concepts that went back decades.

UConn’s Department of Anthropology eventually merged back into one unit in the 1990s, and the exhibit includes a statement from Christian Tryon, the current department head, and a group of faculty and graduate students about the topic.