Passersby always asking you if you’re “lost” on campus. Professors suggesting you wear a tie to class. Security staff relentlessly demanding to see your University ID, then calling the police. Colleagues implying that you’ll easily find an academic job…as a diversity hire, because you’re Black.

These are just a few of the personal stories shared in thousands of online posts by Black academics since 2020, when Associate Professor of Communication Shardé M. Davis’ viral hashtag #BlackintheIvory became one of the most popular on X, formerly known as Twitter.

“I remember thinking: ‘Black in the Ivory’ – that’s exactly it,” the College of Liberal Arts and Sciences faculty member says. “Because I feel like a speck. Like a little black speck on a pristine white garment.”

“Because I feel like a speck. Like a little black speck on a pristine white garment.”

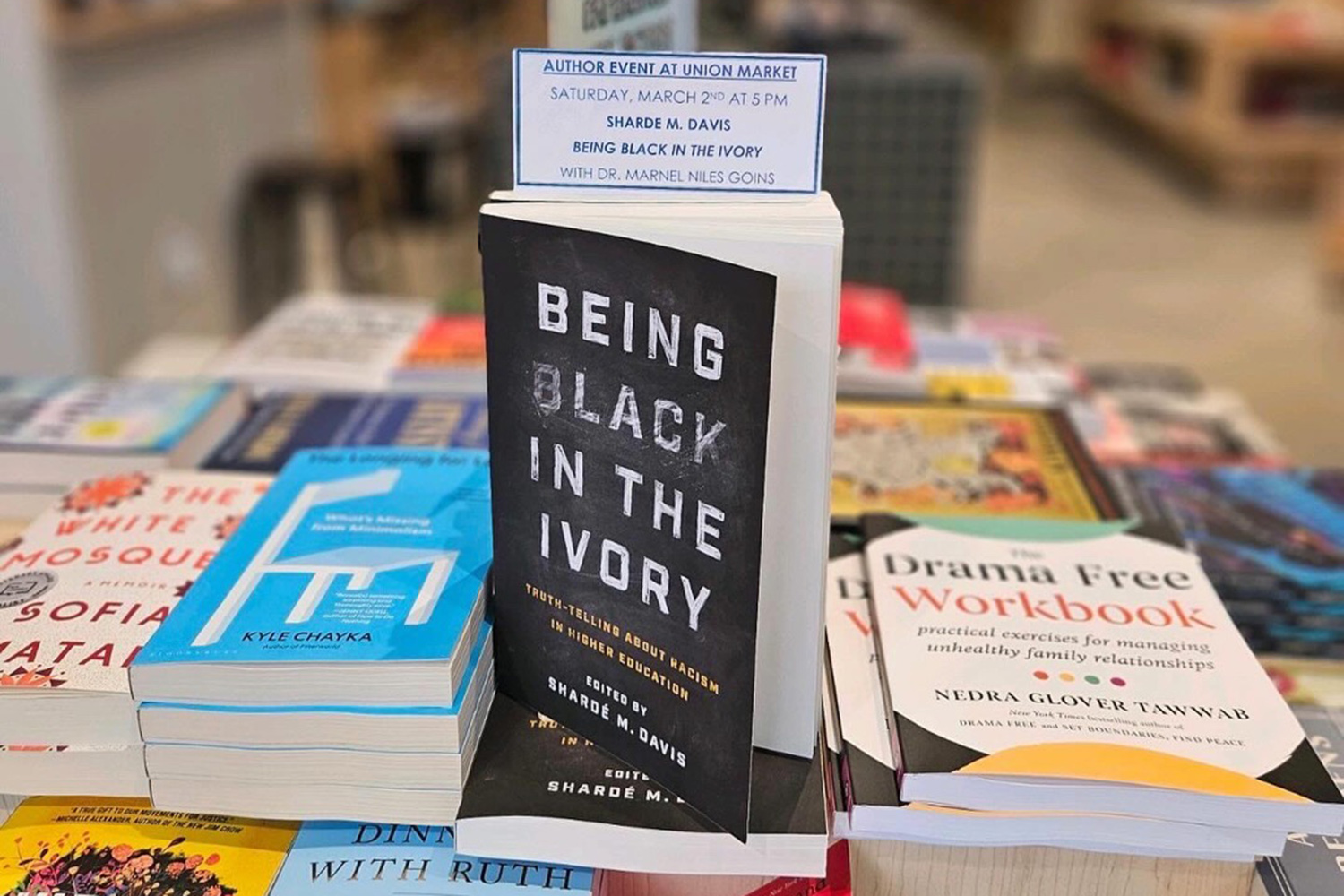

Now, nearly four years later, Davis has published “Being Black in the Ivory,” an edited volume of more than 60 stories told by Black individuals in academia: current and former students, faculty, and administrators.

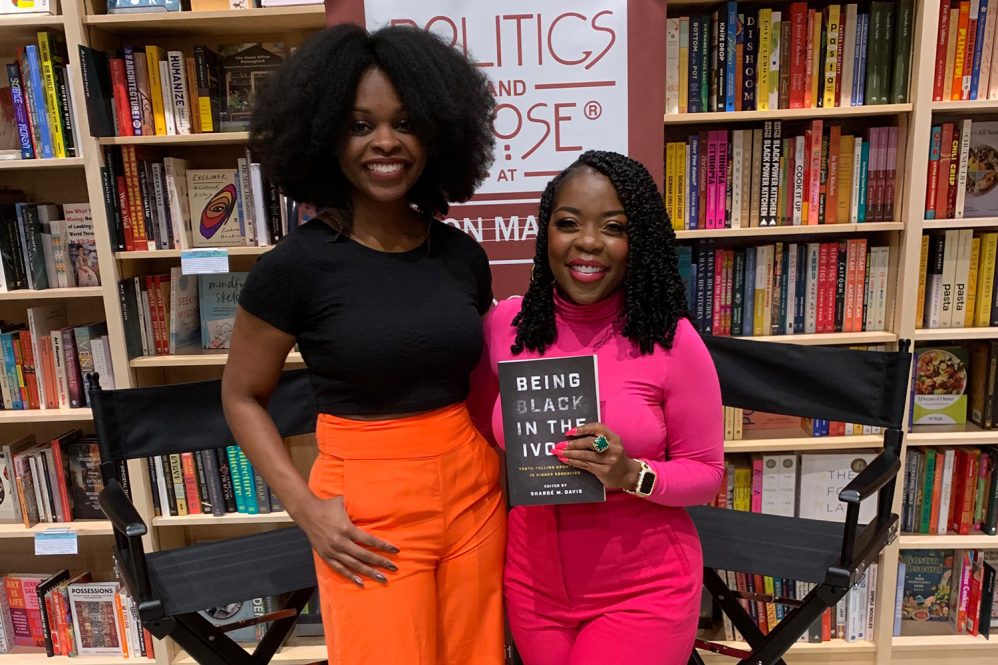

The book, published by the University of North Carolina Press, was released March 2 at a special event and signing at the Politics and Prose bookstore in Washington, D.C.

“It allowed for groundswell, where voices were galvanized literally overnight,” Davis says.

A Groundswell of Voices

In June 2020, Davis sat reeling in her apartment after attending a protest following the murder of George Floyd. The rally hadn’t helped release her built-up rage, and she knew her friends were all emotionally drained, so she didn’t want to call anyone to talk.

Instead, she poured her feelings into a hashtag that would go on to change her life.

“I really felt as though someone had murdered my brother, and that it could have been me,” she says. “Though I had never had a traumatic experience with the police, after taking emotional inventory, I realized that what I was experiencing was a visceral reaction to the underlying root of police brutality — anti-Black racism.”

Davis says she needed something to represent what she was feeling, a phrase that communicated her internal dialogue and personal journey in academia.

Over the following days she drew back the curtain on her normally private approach to social media, using #BlackintheIvory to post honest, ugly truths of the racism she experiences in the Ivory Tower, and reading and interacting with hundreds of other Black academics (Blackademics, she would later call herself and her colleagues).

That so many people rose up in solidarity with her hashtag was a complete surprise to Davis. But she found both the similarity of and the variety among the experiences Black academics described not unexpected in the least.

“None of it surprised me,” Davis says. “The structure of higher education was built without Black people in mind, without recognizing that Black people can be knowledge producers.”

Davis spent many days responding to high-profile media calls from the likes of The New York Times, Nature, and the New Yorker. She felt proud, and glad that her spur-of-the-moment hashtag had helped so many people.

When she also started getting e-mails and direct messages from provosts and presidents of universities, the feedback was overwhelmingly supportive, making her hopeful. But, she says, it also gave her pause.

“That told me that they’re watching, they’re reading,” she says. “And that can go a lot of different ways. It’s part of what it means to be Black in America. We say, colloquially: you have to keep your head on swivel. You can’t get too comfortable.”

As a Black person, Davis says, she is highly visible, and that overexposure can go terribly wrong.

“Sometimes that means our humanity — our imperfections, mistakes, controversial opinions — is so closely monitored that it becomes a feeding ground for heightened scrutiny and excessive ridicule,” she says.

Blackademics

Davis hadn’t even considered the idea of a book when publishers started to call.

“I felt like the idea [for the hashtag] had grown legs, and it was running, and I was running after it!” she laughs. “I hadn’t even considered a book because I was simply trying to wrap my head around a viral hashtag and what it means to facilitate a global ‘capital C’ conversation.”

So Davis deliberately slowed down and thought about her approach to a possible book. The result was selecting the University of North Carolina Press, which is known for its social justice scholarship, she says.

“A topic like this needs to be handled with a lot of care,” says Davis.

Hundreds of people responded to her open call for essay pitches for the book, and Davis also contacted individuals whose stories she hoped to include.

She then spent three years working with the five dozen individuals to help them speak their truth, she says — which was not only a challenging task for her, but for the contributors.

“Sometimes people would be working on a first or second draft, and I’d stop hearing from them,” she remembers. “I’d say, okay, how are you doing, what’s going on? And they’d say things like, ‘Every time I try to sit down and write this, I just can’t. It’s hard for me.’ They were working through their trauma.”

Several contributors use only first names or are completely anonymous. Davis says that speaks to the amount of bravery it required to participate in this project at all. She is adamant that the book is dedicated to Black people — that its purpose is for Black individuals in academia to feel less alone.

“My primary audience are Blackacademics, because being Black in academia is a very isolating experience,” she says. “But everyone can learn something from it, especially about the everyday, covert racial microaggressions, which research shows do just as much harm as overt racism.”

Davis invited her colleague, Marnel Niles Goins, to facilitate a conversation about the book at Washington, D.C.’s Politics and Prose bookstore on March 2. Niles Goins is the first Black woman President of the National Communication Association and Dean of the College of Sciences and Humanities and Professor of Communication at Marymount University.

The event touched on the internalized experiences that Black academics, especially Black women academics, often face that make them convinced they’re not good enough.

“Often [Black academics] think: ‘It’s me, it’s my fault,’” says Davis. “’I’m not smart. I’m not a good writer. I’m too much. I’m too loud. I’m a rabble rouser.’ But no, what we are experiencing is actually just anti-Black racism at its finest.”

Davis hopes that when people read the book, they can visualize the stories within it as more than just essays. She hopes that non-Black academics can learn from it, and that Black academics can use it in their healing journey.

“These aren’t just essays. These are real people’s lives,” she states.

“People should approach the book remembering that, and knowing the amount of bravery and courage that was required for the contributors to lease their stories to the world for everyone’s respective educational, growing, and healing journey.”