What started as a trip to a walk-in clinic turned into a hospitalization and became a medical mystery that went unsolved for nearly four months.

As a writer for UConn Today, from time to time I get to tell a patient’s story to help illustrate the medical care available at UConn Health. This time, to wrap up American Heart Month, I am sharing my own story to raise awareness.

It’s also a real-life illustration of how science and medicine are capable of getting out in front of a disease to mitigate its impact on quality of life and longevity. — Chris DeFrancesco

It’s also a real-life illustration of how science and medicine are capable of getting out in front of a disease to mitigate its impact on quality of life and longevity.

I’m a middle-aged guy who tries to exercise when he can, and my activity of choice is dekhockey; that’s where you play in sneakers gym floor rather than skates on ice. By no means “real” hockey, nonetheless it’s a good cardiovascular workout, certainly of much greater intensity than the golf many of my peers play. I’ve been playing in recreational dekhockey leagues in Plainville for nearly 30 years, one or two nights a week, an hour at a time.

We had a game scheduled the afternoon of Sunday, Sept. 10. A few days earlier I noticed pain in my left shoulder that limited my range of motion. It was only noticeable when I reached a certain way, by no means debilitating. But I figured I should get it looked at and get a ruling on whether playing with it could make it worse.

So that’s what I decided to do that Saturday, the day before the game. I went to a local walk-in clinic that has an x-ray machine. When I couldn’t explain to the medical assistant where the shoulder pain came from — no fall, trauma, collision I could recall — she decided to run an electrocardiogram. The thought was, heart attacks have been known to reveal themselves through arm or shoulder pain, and she was looking at a 49-year-old man carrying some extra pounds with some family history, why not rule it out?

Except she couldn’t rule it out.

She did not like the looks of my EKG, and was troubled by my low resting heart rate, which was around 50. She said I should go the emergency room and get a full cardiac workup, just in case.

I felt fine, but I didn’t argue.

Call an Ambulance

Now I’ve learned enough about cardiology and emergency medicine to know that possible heart attacks warrant ambulance transport. So it didn’t surprise me when she told me an ambulance was on its way. I told the EMTs I’d like to go to UConn.

A blood test in the UConn John Dempsey Hospital ED showed I had an abnormally high level of a protein called troponin. If you have anything more than a trace amount, it can be a sign of a cardiovascular problem, either that has happened or may be about to. The way I remember it explained that day was, you want a score of less than 0.04. A score of 0.5 is a heart attack. Mine 0.26, mathematically about halfway there.

By the way I still felt fine.

I also should point out, my stop at the walk-in that morning was on my way back from, coincidentally, a CT calcium score exam. Eleven days earlier, my primary care doctor had recommended I get one, and that happened to be the morning I went for it. I got the results that day, while I was in the ED: zero, the best possible score — another reason to think I wasn’t having a heart attack.

It eventually was decided to admit me and take more blood every few hours. For the first time, I would be an overnight guest at my employer’s. I had to trade my clothes for a johnny and heart monitor. Fortunately, I was able to get a portable heart monitor, which allowed me to maintain some level of mobility and, therefore, independence.

Over the course of 24 hours or so I had several blood tests, EKGs, a chest x-ray, and surely a few other things. There was no explanation for the elevated troponin. Dr. Joyce Meng, the cardiologist on duty that weekend, said if the troponin showed a downward trend, and the cardiac ultrasound looked OK, I could go home and arrange to follow up with a cardiologist.

Sunday afternoon I was discharged, and soon I would become Dr. Agnes Kim’s problem.

Regarding my one-night hospital stay, I must say, everyone I encountered was incredibly caring and courteous, from the housekeepers to the medical assistants to the nurses to the attendings. The room was comfortable. I was able to relax while waiting this out. When the worst part of a hospital stay is removing the EKG stickers from your chest, you have nothing to complain about.

Not a Heart Attack; Now What?

At discharge, troponin had slipped to 0.22, still high, and was still there more than a week later. A coronary CT angiogram showed normal coronary arteries. It also showed a mild dilation of my main pulmonary artery, which could suggest pulmonary hypertension. A cardiac MRI would follow three weeks later.

Doctor’s orders: Moderate exercise would be OK, but hockey would have to wait.

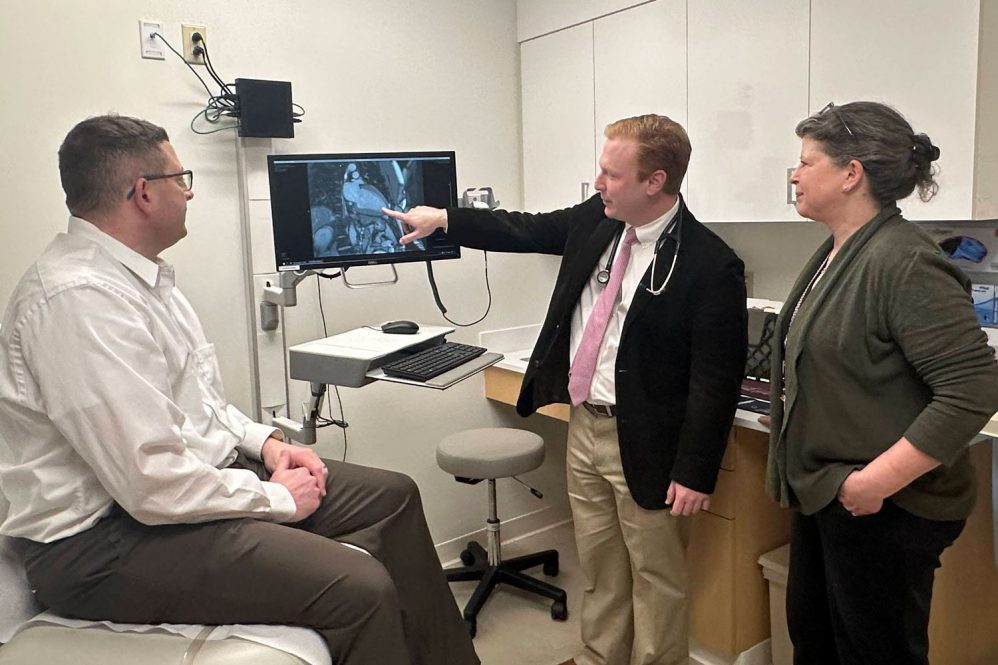

The cardiac MRI ruled out myocarditis, or inflammation of the heart muscle. That might have explained the elevated troponin, but it probably also would have led to new questions. The MRI did not rule out pulmonary hypertension. Next stop would be the cardiac catheterization lab a month later for a diagnostic test to determine pulmonary hypertension by measuring the pressures inside the heart chambers.

Pulmonary hypertension can cause shortness of breath. It’s important to make clear, I’m still not showing any symptoms of that or anything cardiac related. But I also have sleep apnea and that’s been known to have an association with pulmonary hypertension too.

The “right heart cath,” as they were calling it, was a strange experience. Dr. JuYong Lee ran a catheter from inside my right elbow, up my arm, and into my heart. Would it surprise you to learn you’re awake for this the whole time? The explanation was, if they put you under, it throws off the pressure in the heart and prevents an accurate reading. The good news is, apparently we don’t have nerve endings inside of our blood vessels, so I didn’t feel it. All I had to do was stay really still knowing they were fishing a thin wire through my insides.

But we came out of that just fine, made better by Dr. Lee, before he even finished, telling me that I don’t have pulmonary hypertension either.

Still Stumped

By mid-November, the troponin had been holding steady at 0.17 — the lowest it’s been since we started measuring it, but still too high to stop trying to figure it out. And now Dr. Kim is using the term “unusual case of chronic troponinemia.” So now what?

A week later I was on a treadmill for a stress test. It was inconclusive. They cut it short before I could even work up a sweat, apparently because of my EKG irregularities, going longer than seven minutes wasn’t going to provide any new information.

Did I have my care team stumped?

In November, on the morning of my 50th birthday, I got this note from Dr. Kim:

“After reviewing all of your studies in detail and discussing with a few of my colleagues, there are 3 possibilities: (1) You have early-stage hypertrophic cardiomyopathy or maybe Fabry’s disease where we see abnormal ECG and slight troponin elevation but the disease is not showing up on the cardiac MRI yet. (2) The positive troponin is a false positive result due to presence of heterophilic antibodies. (3) There is a small branch coronary artery dissection that was not picked up on coronary CTA.”

From there came a referral to Dr. Travis Hinson, cardiac geneticist with a joint faculty appointment at UConn Health and The Jackson Laboratory for Genomic Medicine, to test for hypertrophic cardiomyopathy and Fabry disease. In the meantime we’d do more lab work to rule out a false positive result.

It’s in the Genes

A week later, I got a call from Jennifer Stroop, a genetic counselor who works with Dr. Hinson. I got her up to speed on things, we talked about my family history for cardiac risk factors, and we arranged for me to see her and Dr. Hinson Dec. 6.

That day we reviewed all the tests and blood work and absence of symptoms, talked more about family history, and, without getting into details about less-forthcoming relatives here, there was enough to recommend a “gene panel test for comprehensive cardiomyopathy and myopathy panels,” and also something called an alpha-galactosidase blood test, which could rule out Fabry disease. By now the additional lab work had ruled out a false positive troponin result. I had settled in at 0.15.

I agreed to these recommendations, got the blood work done, and a few weeks later we had two breakthrough findings:

-

Dr. Joseph Tucker discusses Fabry disease with Chris DeFrancesco at UConn Health’s genetics office in Avon. (Photo by UConn Health Avon staff) A “pathogenic variant” on the GLA gene

- An alpha-galactosidase reading of 0.003

In this case, 1+2 equals a diagnosis of mild Fabry disease. We finally got an answer.

Lots of conversations and paperwork followed, with Dr. Hinson and then with Dr. Joseph Tucker, another geneticist, at the UConn Health office in Avon. Here are my layman’s takeaways:

- Fabry disease is a rare genetic condition that prevents the body from producing enough alpha-galactosidase, which is an enzyme that helps rid cells of toxins or waste. This could lead to problems in one or more organ systems as we age. Two years ago the journal Intractable and Rare Diseases Research reported Fabry disease had a frequency of 1 in 40,000 in men and 1 in 117,000 in women.

- Fabry disease does have an association with elevated troponin. I probably have been outside the normal range for years but never had any reason to measure it.

- There are therapies available to help the body overcome the lack of alpha-galactosidase production.

- Finding out about it at age 50 is quite advantageous to not finding out at all, then having a problem later in life that could have been prevented, treated, managed, or at least delayed.

Dr. Hinson said there probably couldn’t have been a better time to find this.

And that’s the story of how cardiovascular genetics solved a riddle that undoubtedly will change the trajectory of my health. The standard lifestyle recommendations on diet and exercise of course still apply. I returned to playing hockey after four months, and I’ll probably start taking a new medication. Most notable will be more frequent check-ins with a variety of specialists, to establish baselines for different organ systems and monitor them, knowing what to watch for as I get older.

It’s also a real-life illustration of how science and medicine are capable of getting out in front of a disease to mitigate its impact on quality of life and longevity.

And it’s a reminder of how fortunate I am to have access to some of the most incredible minds in medicine, plus the most capable imaging and lab medicine technicians, and all the other wonderful UConn Health staff who had a hand in my care.

In that way, this is also a long thank-you note to all of them — and to the medical assistant at the walk-in who sent me to the hospital, touching off a sequence of events that history may show ended up saving my life, or at least prolonging it.