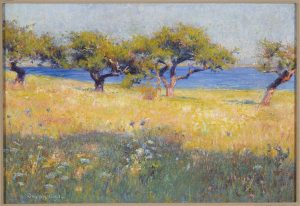

In 2019, local artist Blanche Serban started a project painting Horsebarn Hill every day for the whole year. The paintings capture the landscape’s changes across the seasons, each day bringing something new. The study of such seasonal changes in natural phenomena — phenology– can tell us a lot about prevailing conditions and long-term trends. Her 365 paintings got Department of Earth Science Professor Robert Thorson wondering whether historic art from the Benton Museum could help us see phenological changes caused by climate change.

With the help of Curator and Academic Liaison Amanda Douberley, Thorson created an exhibition exploring this question, which opened at the Benton on January 16th and will run through July 28th.

‘Seeing something is not the same as looking at something’

The exhibition presents a partnership between art and science, one helping to deepen the understanding of the other to hopefully broaden what we see.

“Artists always override and influence reality, which is what they’re supposed to do,” says Thorson.

The exhibition’s primer explores six themes including phenology, climate change, measurement, climate, weather, and seasonality while featuring works in the Benton’s permanent collection to explore these themes in five sections. As a geologist who spent years publishing papers reconstructing the Earth’s past climates and teaching about current global climate change, Thorson challenges visitors to experience the art through a geological lens to develop a mindfulness of how climate change is impacting their lives.

Upon entering the exhibition space, visitors are met with two paintings, one of a winter snowfall, and one depicting a fall scene with bright yellows and an outcropping of large, smooth stones that seem to undulate across the landscape. Thorson explains they are descriptively named “whalebacks”:

“See, even in this painting, you see geology.”

Initially, Thorson approached the Benton with the idea of studying phenology through art,

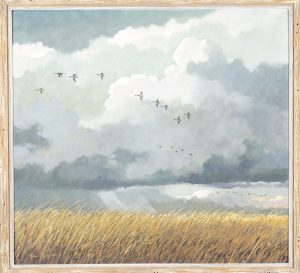

“If paintings captured what a landscape looked like every day of the year, then one could reference that in the future and see, for instance, whether or not there are snowbanks or the timing of flowers blossoming, or the birds flying, and whatever the future timing of those events would be earlier or later,” says Thorson.

Douberley and Thorson realized early in the proposal stage that most of the artwork did not have the specific date and location data vital for studying phenology. Douberley also points out that creative license taken by artists can complicate using paintings and drawings as scientific evidence for the study of phenology. But after reconsidering, Thorson reasoned that exact dates were not necessary to show changes over time or to think about what the future holds.

“If we were unable to see climate change via the phenology of then-and-now comparisons, perhaps we can learn to see the effects of weather in paintings, regardless of whether the artist was aware of them or not. This is the theme the exhibition is based on,” says Thorson.

‘Then and now. Now and future’

With climate change, phenology is disrupted for many plants and animals, from periodical cicadas likely emerging earlier, to certain plants setting leaves or blooming weeks earlier, the seasons are shifting.

Looking at the collection of paintings, etchings, drawings, and photos, observers are encouraged to ask questions like “How would this look if it were painted today?,” or “What will this look like in 2100?.” The themes capture some of the pressing changes on the horizon, from rising seas to desertification and changing urban climate.

“One painting is from 151 years ago in the Boston Harbor and as Boston grew, the additional asphalt and stone warmed the urban climate more than the adjacent areas and superimposed regional warming,” explains Thorson. “It shows foggy conditions, but how might the patterns of fog have changed since then?”

An etching shows Paris in 1879 after thick snowfall, but the city receives only minor snow today. A couple of prints show Venice, which is already grappling with rising sea levels. To emphasize local conditions, paintings and drawings show the New England coast, and Thorson explains that coastal erosion means the landscapes depicted may no longer be there because the coast has eroded by tens of meters since the paintings were finished.

“I want people to be mindful of phenological changes and more aware of how their lives are already being impacted by climate change,” he says. “If you can see changes, not just from the news, but in your own life, that’s important. My premise is to help people become more mindful and take further action.”

Thorson approaches this challenge carefully from the outset which can be seen in the first two sentences of wall text:

“The projections for climate change during our lifetime are scientifically robust. The outcomes will be generally disruptive, and the costs will be shared unevenly across the globe.”

“This is serious business,” Thorson explains. “We start with a fact, but we don’t want to be too harsh.”

The text goes on:

“Being mindful of climate change in your daily life can help you make the needed adaptations towards a more just and sustainable future.”

Creating that personal connection to climate change is vital. The exhibition also included eight photos of familiar sights around Connecticut where Thorson asks the question “What will this look like in 2100” with captions that help get the observer thinking about specific changes on the horizon.

“Will we have the same kind of trees? How will the coastal marshes look with rising sea levels? Will the sandy soils continue to be productive in extended times of drought? These are the kinds of questions I asked that I want people to be thinking about because the odds are these things will look very different.”

Douberley says the feedback has been very positive so far.

“The response to the exhibition from instructors has been fantastic. We had four classes visit this week alone! Professor Thorson’s engaging wall texts make the show ideal for students and serve as instant conversation starters.”

The importance of a question mark

Thorson was careful in his approach and explains that the question mark in the exhibition’s title was intentional. Rather than telling people what they are seeing, he wanted to actively engage observers.

“It’s very different to ask a question, ‘Can you see climate change?’ than to state that ‘You can see climate change.’ Every one of us sees the world differently, we have a model in our heads for what the world is like. I think science makes information and the humanities and the arts make meaning from that information.”

This collaboration between science and humanities can help us engage with the question. Thorson points out an important distinction to help grapple with the concept that weather and climate are not the same.

“I like to quote Mark Twain: ‘Climate is what we expect, weather is what we get.’ We cannot see climate, what we see are the effects of climate.”

‘Continuous Change’

To help emphasize the distinction between climate and weather, the exhibition also displays rocks and tools from Thorson’s teaching collection in separate pedestals. The tools measure current weather conditions. The rocks indicate dramatic climatic conditions in Earth’s past. Thorson chose a colorful variety of clues from black coal to red petrified wood, to white coral, to a brown stone faceted by sandstorms.

“We can see climate in the rock record. Rocks tell the story. Geologists first detailed climate change by telling these stories and that’s one of the reasons that I taught the first course on global climate change mechanisms here at UConn in 2002. Rocks are proxy records for climate we can understand by figuring out things like what’s the threshold temperature or condition to generate ice sheets or the wind speed needed to pick up billions of grains of sand and heap them together. Coral reefs only exist in a certain temperature range and that gives you an envelope of paleoclimate.”

The final images show climate clues from UConn’s little-known Stone Pavilion. The slabs fronting it and the stones from which it was built are glacial in origin. One of its specimen stones is from an ancient coral reef in Iowa, which used to be as salty as it was subtropical.

The exhibition ends with the idea that though change has been continuous, it’s now happening at a much faster pace than normal. Thorson points out that this epoch of Earth’s history is referred to as the Anthropocene, from the Greek for “human,” since humans are the driving force behind these rapid changes.

The rapid rate of change is visually represented on a screen playing the Berkely Earth animation of global mean temperature anomalies from 1850 to 2022. The eerily mesmerizing loop starts largely blue, then gradually grows increasingly red as the dates draw closer to the present, as temperature anomalies creep and remain above normal and toward less livable for many humans. The data corresponding to the colorful trends are sobering.

Pointing at the end of the animation, Thorson says, “2023 would have been literally off the chart since it was the hottest year on record.”

Though it is a continuous part of Earth’s history, previous climatic changes usually took tens of thousands of years, while current shifts are taking decades. The exhibition ends with a bittersweet send-off:

“Earth will continue to be a beautiful place…. with or without us.”

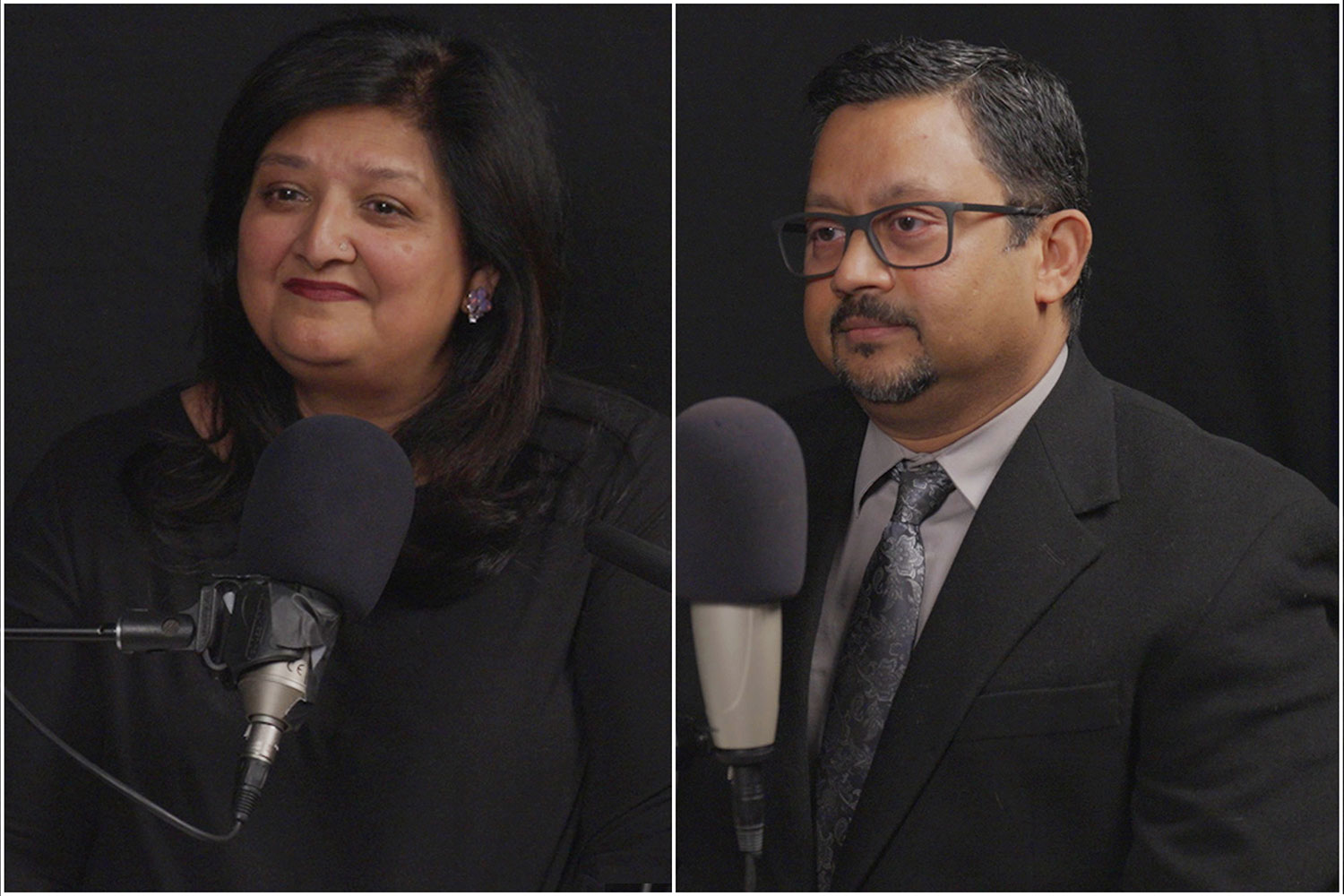

There are upcoming public programs associated with the exhibition including one on February 16, where Thorson will lead a walkthrough of the exhibition and another on March 1 where the Benton will host “Building a Sustainable Future,” a salon mounted in collaboration with UConn’s Werth Institute for Entrepreneurship including a discussion panel that will examine how the next generation is leading the charge of building a more sustainable tomorrow. The exhibition will also be complemented by a podcast that invites listeners to explore climate change through visual art, personal reflection, science, and conversation. The podcast is a production of students enrolled in Collaborating with Cultural Institutions and hosted by WHUS Radio and will soon be available.