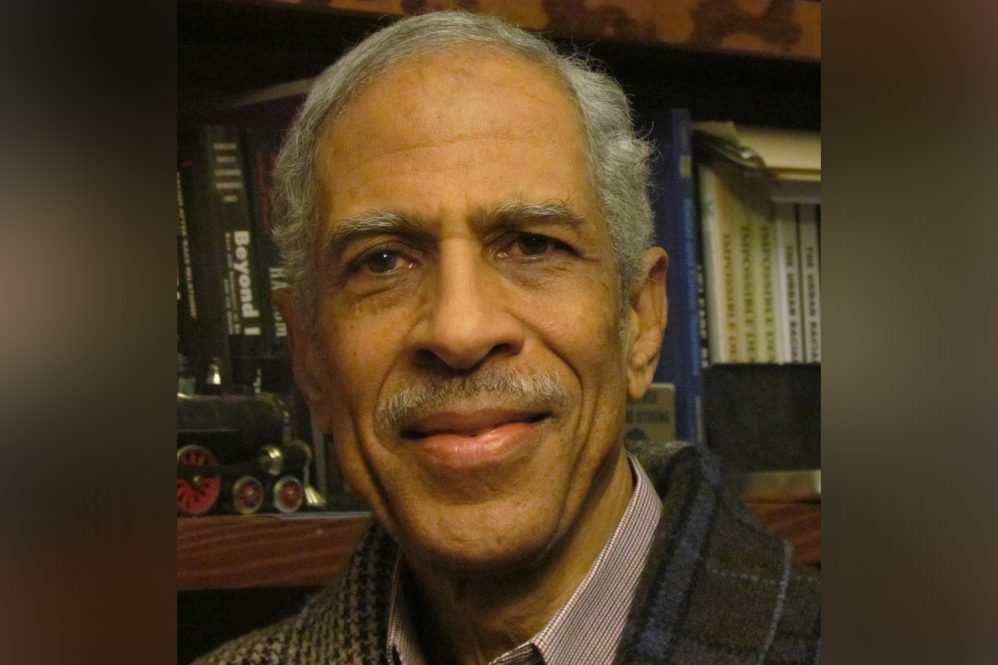

UConn sociologist Noël A. Cazenave knows what Merriam-Webster says about being kind – of a sympathetic or helpful nature; of a forbearing nature, gentle; arising from or characterized by sympathy or forbearance.

In his latest project, though, he’s challenging that definition to ignite a kindness revolution, one meant to shift power relations in pursuit of societal change.

“Kindness - it’s not a word oftentimes used by researchers. They have more specific terminologies that can be more scientifically defined, like altruism, empathy, and caring,” the sociology professor in the College of Liberal Arts and Sciences says. “I wanted to use ordinary language, and I thought it was important to do that because most people have some sense of what kindness is and realize it’s important.”

Cazenave spoke with UConn Today about six weeks before his latest book from publisher Routledge, “Kindness Wars: The History and Political Economy of Human Caring,” is published and about six months before he’s set to appear in “Why Love?,” a documentary from motivational speaker Todd Huston that looks at the concept of love through the eyes of those who study it.

How do you see kindness?

Kindness must be considered as something much larger than just random acts of benevolent individuals. We must recognize that it is a multidimensional phenomenon involving thoughts, feelings, and actions, and it exists at many different levels, from the self, to the interpersonal, to the group, to the formal organizational, to the institutional, to the societal, to the intersocietal, to the universal. We need to return its size and scope to that of the Enlightenment era, a time when kindness was a much larger, more robust, and politically engaged concept. It’s an idea of kindness that departs from the notion that just saying “kindness” or “love” three times is going to magically make for a better world. What we need to promote is a kindness movement that takes universal loving-kindness seriously and doesn’t reduce it to the level of just one person being “nice” to one another. Such a tiny and effete conceptualization of kindness tends to reinforce the status quo of being “kind” and “civil” to each other by staying quiet in the face of societal, economic, and political injustices.

Why is now a good time to consider this?

There are authoritarian movements throughout the world right now in which, contrary to the Enlightenment notion of reason, people are ruthlessly imposing their will on others, infringing on basic human rights, and doing so in ways that are willfully ignorant. Reason doesn’t matter anymore because facts don’t matter. There’s a tendency to see others as the enemy and to empathize only with those seen as one’s own. Shouts of Black Lives Matter have been met with shouts of All Lives Matter, Police Lives Matter, and White Lives Matter. Politicians like Donald Trump have been able to make very empathetic calls of caring for their constituents based on hatred of those deemed to be their enemies. This is a very important time to talk about kindness and try to launch a kindness revolution, but that revolution can’t ignore the role of power. Martin Luther King Jr. did not ignore power when he talked about love. And Gandhi did not ignore the role of power when he used nonviolence to force the British out of India. Indeed, if we’re going to have a real movement toward kindness for everyone and everything on this planet, we must change power relations.

Where does a researcher start to look at something like kindness?

I started with myself. I’m a tenured full-professor who has been very disciplined and focused on his work over the years. On many occasions, when people have asked me to do things, I have said no and felt badly about it. I was saying no because I was frightened that if I spent too much time doing something else my ability to publish would have suffered and I would have therefore been vulnerable for being outspoken about the issues I cared about. At the outset of this project, I wondered how some people have the courage to be kind, to open up and remove their armor to let other people in, while other people, like me, oftentimes don’t. We insulate ourselves, go about our business, and as a result aren’t necessarily kind. Then I realized this was also a sort of higher consciousness or spiritual project. I’ve done a lot of research on racism, poverty, and things like that – I call them my “misery projects.” My last book is called “Killing African Americans: Police and Vigilante Violence as a Racial Control Mechanism.” I’m a Buddhist practitioner, and 30-plus years of meditation practice prepared me to go to terrible places to do such work. But I also wanted to use that interest in higher states of consciousness and human possibilities to more explicitly examine, broaden, and deepen our conceptualization of kindness beyond the popular and myopic views of human caring that in highly individualistic and self-absorbed societies like the United States actually support the all-too-often cruel and uncaring status quo.

What was one of your biggest takeaways?

I realized I’m never going to be an enlightened being, but maybe my contribution is to help reframe this notion of kindness so that we take it seriously and use it to build a genuinely kinder world. Unfortunately, calls for “kindness” and “civility” are oftentimes used as a way of keeping people quiet. I’m a progressive African American who grew up in the South during Jim Crow, so I bring a different perspective to the table than civility-obsessed and conflict-averse white moderates and liberals. Central to the Civil Rights Movement is the notion of “No Justice, No Peace!" People who are oppressed know you must shift power relations to bring about change. Those in power are not going to change just because it’s the right, the rational, and the reasonable thing to do. It’s my job, therefore, to approach the notion of kindness from a very different perspective, to reconceptualize it as a large, robust, and politically engaged concept.

Where does the average person start?

We must recognize that genuine kindness involves group relations, and oftentimes unkindness happens within hierarchies, where one group is more powerful than another. To create a kinder society means challenging power relations in ways that force people to see others outside of their own group as being fully human and deserving of compassion. For example, prior to the late 1970s, there used to be comic strips that showed men in power chasing women around their office desks, and that was all too often considered to be funny. When the women’s right movement emerged, it wasn’t accepted as funny anymore and was called sexual harassment. Until they were punished for that behavior, many men did not have a clue it was wrong. Apply that to today when we have police officers and vigilantes who seem to have no conscience when it comes to killing unarmed African Americans. They are not killing affluent European Americans who can hire lawyers and cause them trouble, because there are consequences for doing so. For African Americans, there are fewer consequences. Until that changes, until the power dynamic is shifted, those who engage in such inhumane cruelty won’t understand it’s wrong. To have a genuine movement for kindness, we must also have a radical redistribution of income and wealth that’s facilitated by government policies. But we have people in power now who are not interested in being kind, who have mean-spirited ideologies like social Darwinism and want only to protect what they have. Take the story of a politician who, on the way to their office to cast an important vote on homelessness, passes a homeless person and puts a dime in that person’s can. The politician feels good about themself, and then goes into work and votes in favor of legislation that essentially criminalizes homelessness. They walk away from the homeless person in the morning thinking they’re kind, but in the afternoon show just how unkind they are.

But aren’t there times when one must come across as being unkind to bring about ultimate kindness and change?

In Buddhism, there’s this notion of genuine versus fool’s compassion, which means that if someone is doing something wrong it needs to be chastised. Bogus or unreal compassion is to encourage that person to continue their harmful ways. For example, if a mother found out her son was using fentanyl, what’s the appropriate response? To smile? That would be the civil thing, to do what we normally think of as “kind.” Another response might be tough love, maybe some willingness to engage in conflict in the moment that might result in genuine kindness in the end.