A team of ecologists with ties to UConn’s Department of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology (EEB) is taking part in a massive NASA-funded international project aimed at helping scientists understand and mitigate the rapid loss of biodiversity due to climate change, development, and other threats associated with human activity. BioSCape, a collaboration between NASA and the South African National Space Agency (SANSA), will employ airborne imaging technology and field observations to survey South Africa’s Greater Cape Floristic Region (GCFR), home to two global biodiversity hotspots rich with flora and marine species found nowhere else on Earth.

Adam Wilson ‘12 Ph.D., an Associate Professor of Geography at the University of Buffalo, is one of two U.S. leads on the project with Jasper Slingsby, a researcher at the University of Cape Town in South Africa. Other UConn researchers involved in the effort include Research Professor Cory Merow and Henry Frye ’23 Ph.D., a post-doctoral researcher on the project — both of whom have received NASA funding to pursue parallel project-related research.

“This is the first international effort of this scope for our group,” says Cynthia Jones, Professor Emerita of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology at UConn, who is co-PI with EEB Professor Emeritus John Silander, on the NASA grant funding Frye’s work. “South Africa has one of the most advanced conservation efforts in the world. With nine plant biomes, three of which are at the tip of South Africa, it is one of the most ecologically diverse places on the planet.”

The project is expected to begin this fall, with both Merow and Frye participating in the airborne component of the work. They and other researchers will use four kinds of airborne sensors to collect full-spectrum imaging spectroscopy, and laser image detection and ranging (LIDAR) data, from planes flown over land and water.

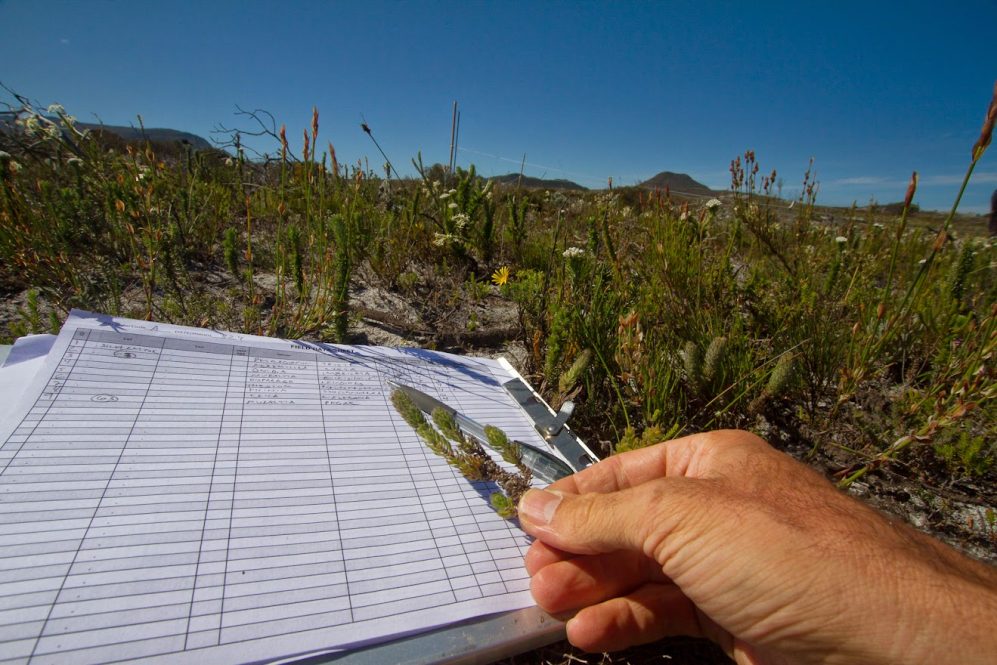

The sensors are essentially fancy cameras that take pictures from the plane as it flies over a pre-determined area, explains Merow. Some are designed to detect vertical structures, while others produce high-resolution images that record all colors and are useful for examining plant traits. A separate team of researchers will observe the same vegetation at ground level at 200 locations.

“The idea is, if you have an association between what’s on the ground that the airplane measures, you can predict everything that’s measured from the airplane,” Merow said. “It’s the first step in automating biodiversity monitoring. We can already gauge how plants recover from fires; determining what species are there, and their traits, is the next step. This will add another layer to our common understanding of monitoring. This is a baseline for starting to track changes.”

Frye specializes in interpreting data produced by the high-resolution, color-recording imaging technique known as hyperspectral imaging. Instead of assigning only primary colors to each pixel, these images record and analyze a wide spectrum of light that, when broken down into many different bands, provides more information on the object being imaged.

Frye has employed the technique to study mangrove systems in Florida and, as part of his doctoral work, cleaned up baseline data generated through a previous National Science Foundation–funded project in South Africa led by EEB Professor Emeritus Carl Schlitchin. Frye’s work with the BioSCape project builds on his long-standing interest in remote sensing data and grew out of a 2016 proposal he wrote with Silander, Wilson, Merow, and their South African partners, and pitched to NASA.

“It’s really critical to understand what’s going on with the planet and make realistic decisions,” Frye says.

“Since we are modifying environment that species depend on, we need to understand the processes that cause them to respond, which will help inform mitigation decisions,” adds Merow.

BioSCape fieldwork will take place over six weeks, with planes based out of a station in South Africa flying in predetermined lines and gathering data with sensors. The six months of preparation leading up to the field campaign have included large group meetings of 60–70 researchers to discuss where to fly the airplanes and how to calibrate the sensors. Researchers from more than 30 academic institutions and scientific organizations have partnered for the project.

BioSCape is NASA’s first ever biodiversity field program combining airborne spectroscopy, LIDAR, and field observations across the GCFR. The project is being driven on the American side by the Earth Science Division (ESD) of NASA’s Science Mission Directorate. ESD missions focus on better understanding Earth’s interconnected systems using observations from satellites, the International Space Station, airplanes, balloons, ships and on land to collect data ranging from ocean currents and temperatures to land use and vegetation.

“When we see the name NASA, we associate it with sending people to the moon,” says Frye. “But there is so much science NASA does looking at our planet and looking from above. This is an area where we get a lot of bang for our buck. So much knowledge can be built from this project.”