Suicides and suicide attempts by Black and Hispanic Americans are on the rise. Changing the way doctors, clergy, and school personnel think about risk may be essential to prevention, reports a UConn Health researcher.

Suicide in the US is relatively rare, and suicide among Blacks and Hispanics in the US has historically been thought to be even rarer than in the population overall. Data from the early 1980s that tracked suicide attempts (which are more common than suicide, but closely correlated) found that white people were 1.7 times as likely as Black and Hispanic people to attempt suicide. Data from the mid 1990s shows little difference between the groups.

But recently that trend has changed, reports UConn School of Medicine psychiatric epidemiologist Greg Rhee in the Sept. 15 issue of Psychological Medicine. He and colleagues from Yale School of Medicine found that recently, non-Hispanic whites have become slightly less likely to plan to or attempt to kill themselves, while Black and Hispanic people have become somewhat more likely to make the attempt.

The researchers looked at data from the 2009-2020 National Survey of Drug Use and Health, an annual survey of adults across the US that asks whether people have imagined suicide (suicidal ideation), and whether they have actually attempted suicide, in the past year. The survey data showed that overall, adults in the US became slightly less likely to have attempted suicide in 2019 and in 2020 than in prior years, the first time since 2009 those numbers have decreased in two consecutive years. But breaking the data down by race and ethnicity shows that decrease disappears for Black and Hispanic people.

Black and Hispanic Americans were also less likely to report suicidal ideation, but they were more likely to report suicidal attempts. Because those populations seem less likely to report less serious signs of suicidal intent, friends, doctors, clergy members, and other people in their lives may be less likely to notice the signs in time to help them.

“We hope to shed light on rising rates of suicide among Black and Hispanic individuals,” says Rhee. “The earlier someone at risk of suicide receives an intervention, the more likely it is to be successful,” and the less likely they are to make an attempt, Rhee says.

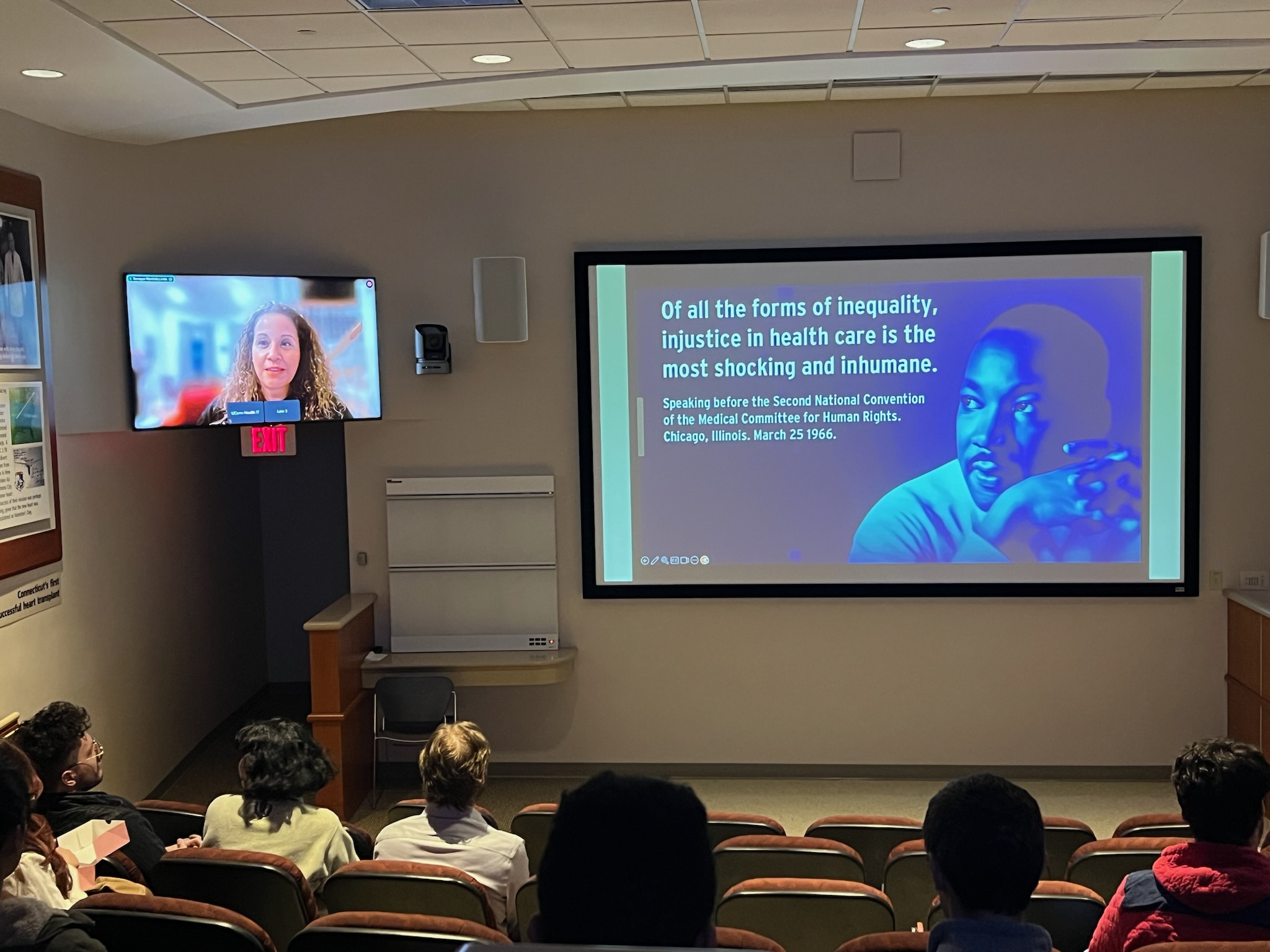

In general, Black and Hispanic people in the survey were less likely to receive mental health services than whites. Hispanic individuals in particular cited an unwillingness to have other people know they were getting treatment; both groups said they had trouble accessing care close to where they lived. Clinicians, social workers, and others developing suicide prevention strategies should carefully assess socio-cultural norms for expressions of distress and stigma, and include them in educational strategies for doctors, teachers and clergy in the community.

The researchers are currently investigating how other psycho-social factors such as social support, social connection, and loneliness could influence the relationship between race/ethnicity and suicidality. They hope to better characterize those factors that increase risk and those that protect people.