[Editor’s Note: A version of this article appeared Sunday, Nov. 29 in the New York Times]

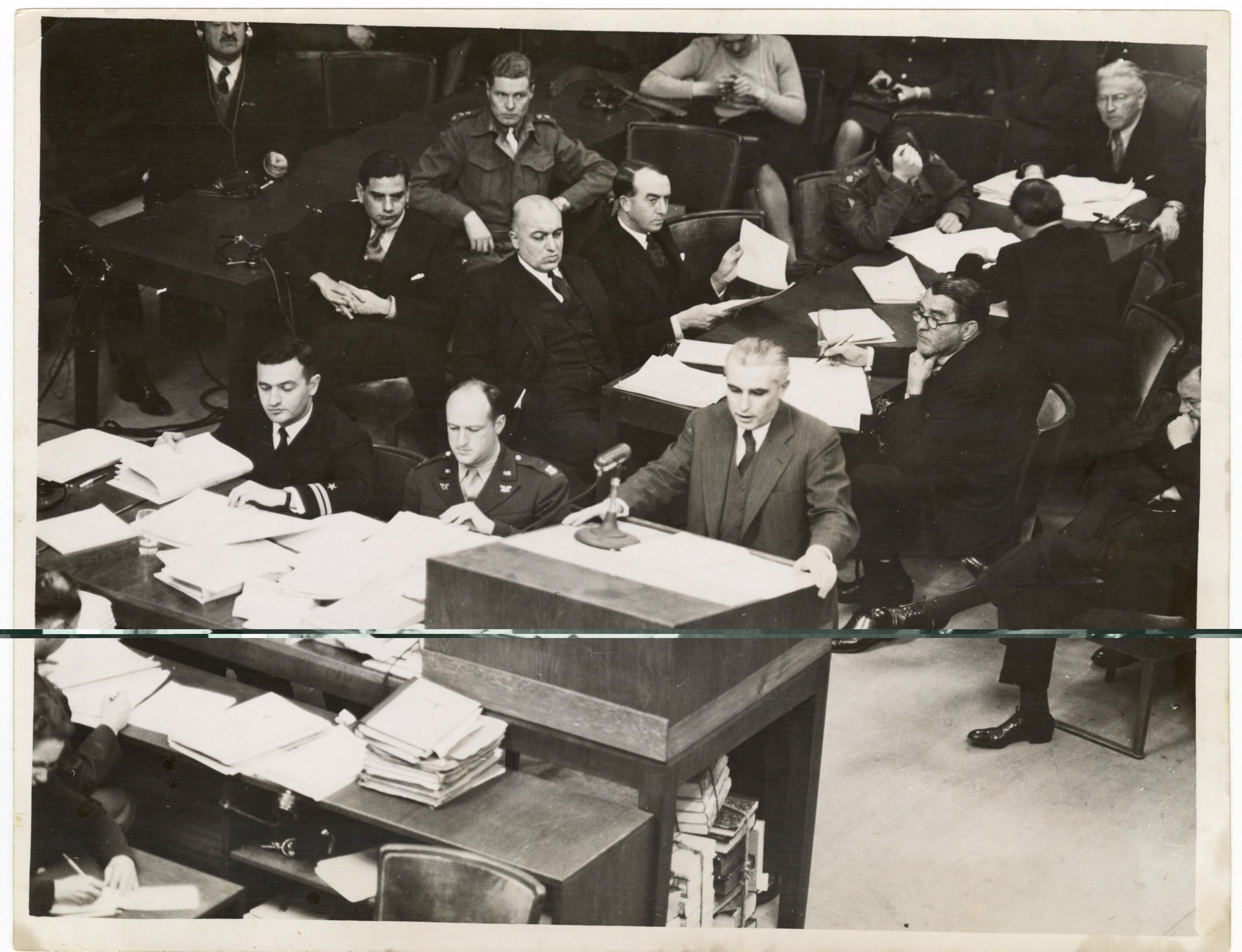

Seventy-five years ago this week, my father, Thomas J. Dodd, stepped to the podium to address for the first time one of the most important trials in history: the International Military Tribunal at Nuremberg.

Over the next 11 months, he and his fellow prosecutors presented overwhelming evidence of the machinery of death and destruction, as well as the poisonous ideology of Aryan racial supremacy, that had killed tens of millions of people, including six million Jews. These were crimes so ghastly, the chief prosecutor, Justice Robert H. Jackson, said, “that civilization cannot tolerate their being ignored, because it cannot survive their being repeated.”

Jackson’s address is widely regarded as among the greatest speeches in legal history. My father’s words the following week were less epoch-making; he introduced a screening of a short movie. The film, titled “Nazi Concentration Camps,” was described by my father as “brief and unforgettable” and presented as “an explanation of what the words ‘concentration camp’ imply.”

Compiled by the U.S. Army Signal Corps from footage filmed between March 1 and May 8, 1945, the film depicts Buchenwald, Dachau, Bergen-Belsen, and several other camps upon liberation by Allied forces. Images of mass graves, ash-filled crematories, and the broken and emaciated bodies of men, women and children flashed before a stunned court as clear, graphic and undeniable evidence of the atrocities we have come to know as the Holocaust.

In the months that followed, my father and his colleagues worked to connect the two dozen high-ranking German leaders to these horrific scenes through a mountain of documentary evidence. The film, the documents, the testimonies — all of it was dedicated to presenting before the tribunal and world the truth of what the Nazis had done and to hold them to account under the rule of law under the key principles of human rights and equal justice. For many at Nuremberg, there was hope that these principles would help break the cycle of vengeance and destruction and put the world on the path of peace through the protection of human dignity for all.

Today, that path is still before us. Human rights, the rule of law and even truth itself are threatened by continuing violence, resurgent authoritarianism, racism and anti-Semitism, and rampant conspiracy theories, propaganda and disinformation.

We are reminded that the lessons of Nuremberg must be continually relearned and that the work of protecting dignity and promoting justice are the responsibility of each generation. Amid the devastation and ruin of Nuremberg, my father and his colleagues sought a reckoning with the past so that a brighter future might be possible. Today, the trial is an important reminder that facts matter, the truth matters, and the rule of law matters.

As we face these new challenges to human rights and democracy, I’m proud to know that the work of my father, Justice Jackson, and the prosecutors at Nuremberg, fighting for human rights and the rule of law, is carried on through the Dodd Human Rights Impact at the University of Connecticut’s Human Rights Institute.

In the coming year, through the work of our scientists on a Covid-19 vaccine and with the leadership of the Biden administration, we will emerge from the fear and isolation this pandemic has created. We will then have the responsibility to renew our commitment to the universal values of human rights, and the opportunity not only to reconstruct our democracy as it was, but also to build a better, more just democracy for all.