When some of us get frustrated with life or painful conditions, we turn to yoga, finding relief and relaxation in the breathing, postures and meditation.

Nurse researcher Angela Starkweather, who studies pain genomics, mechanisms, interventions, and management, is no different.

“Pain is often a significant frustration to patients and health care providers, because there is still a lot of trial and error involved in finding the best approach for managing pain,” she says. “We have a lot of evidence about the genetic linkages that make some people more vulnerable to chronic pain, but we have very little information about which interventions will work best to reduce pain based on the individual’s genetic background.”

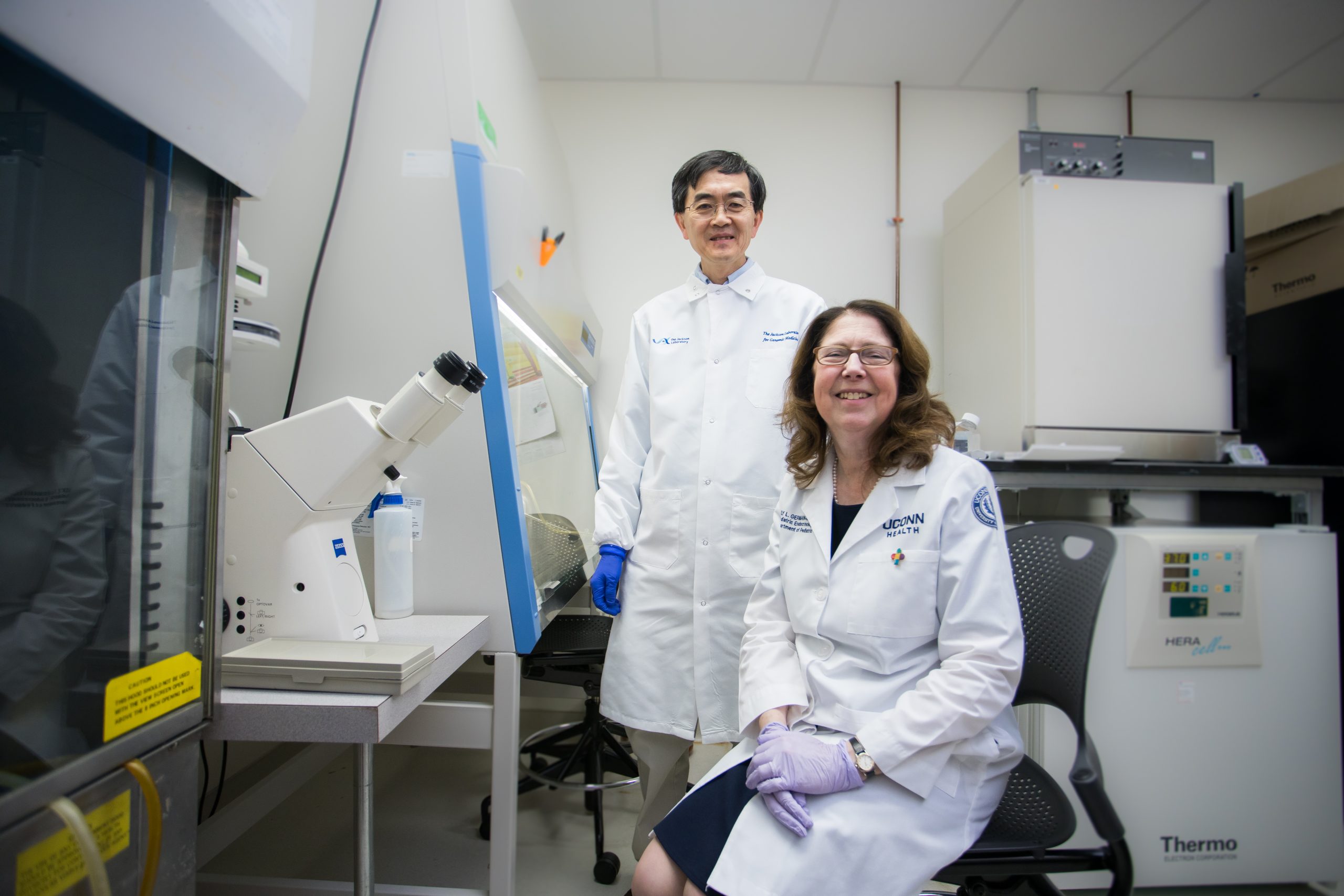

So now Starkweather and another UConn professor, internationally renowned yoga investigator Crystal Park, are turning their attention to some of the non-pharmacological methods for pain treatment — specifically, studying how yoga helps individuals with chronic low back pain. The study has received a $3 million grant from the National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health, which is one of the 27 agencies under the National Institutes of Health.

“We know that, for many people, yoga works well to reduce pain, but we don’t know why it works for some people and not others,” says Starkweather, who is also the School of Nursing’s Associate Dean for Academic Affairs.

She is partnering with Park, of the College of Liberal Arts and Sciences’ Department of Psychological Sciences, to lead an interdisciplinary team that will focus on integrating psychological, neurophysiological, and genomic data in this study.

The two researchers’ goal over the five years of their grant is to identify the mechanisms through which yoga helps people with chronic low back pain to achieve better control of pain and physical function, and therefore how the components of yoga can be optimized to help more patients with chronic pain conditions.

“There are a lot of different components in yoga,” Starkweather says. “There’s the breathing, the postures, and meditation, which each help to manage pain in a different way.” In this study, she and Park are focusing on whether these aspects of yoga improve pain outcomes through a pathway of improved emotion-regulation.

“We know that yoga improves chronic low back pain — there is strong evidence of this — but we don’t understand the mechanisms through which it works,” Park says. “By understanding these mechanisms, we can design more effective interventions. We hypothesize that learning to better manage distress and discomfort will help with pain outcomes above and beyond the physical benefits of strengthening and stretching.”

During the study, participants will attend yoga sessions twice weekly for their low back pain. After three months of classes, the researchers will follow the participants for three more months to see if the intervention has longer-lasting effects.

Park will oversee the psychological measurements and ensure the yoga instructors deliver the yoga in the same way. Starkweather will oversee the sensory exams and genetic assays from participants several times throughout the study to examine whether the yoga classes cause changes in transcription of certain genes. Transcription is a cellular process in which a gene’s DNA sequence is used to make an RNA copy. For a protein-coding gene, the RNA copy, or transcript, carries information needed to build a protein or protein subunit. In turn, the transcription of certain genes can influence biological pathways that regulate pain processing.

“We have found that people with chronic low back pain have a unique transcriptomic pattern compared to people without chronic pain, so we will be able to determine whether the intervention affects pain at the cellular level,” Starkweather says. “We hope to use this information to remove the trial-and-error approach and bring us one step closer to personalized management of chronic pain.”

Working with UConn’s Institute for Systems Genomics, Starkweather and graduate students will take blood samples from participants before the start of the study, at six weeks and 12 weeks of classes, and then three months and six months after the classes conclude.

All data collection will occur locally, in lab space at the Arjona Building in Storrs, UConn Health, and Hartford. The School of Nursing’s Center for Advancement in Managing Pain (CAMP) will also be a partner in the project.

“It’s going to be informative to health care providers, and our main goal is to improve the experience and quality of life for the person with chronic pain,” Starkweather says. “That’s what it’s all about.”

This study is supported by a National Institutes of Health grant, Proposal No. R01AT010555, from the National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health; UConn’s Institute for Collaboration on Health, Intervention and Policy (InCHIP) is the managing institute for the grant. Please visit nccih.nih.gov for more information, and visit chip.uconn.edu to learn more about InCHIP.

If you’re interested in participating in the study, visit painresearch.uconn.edu/study.