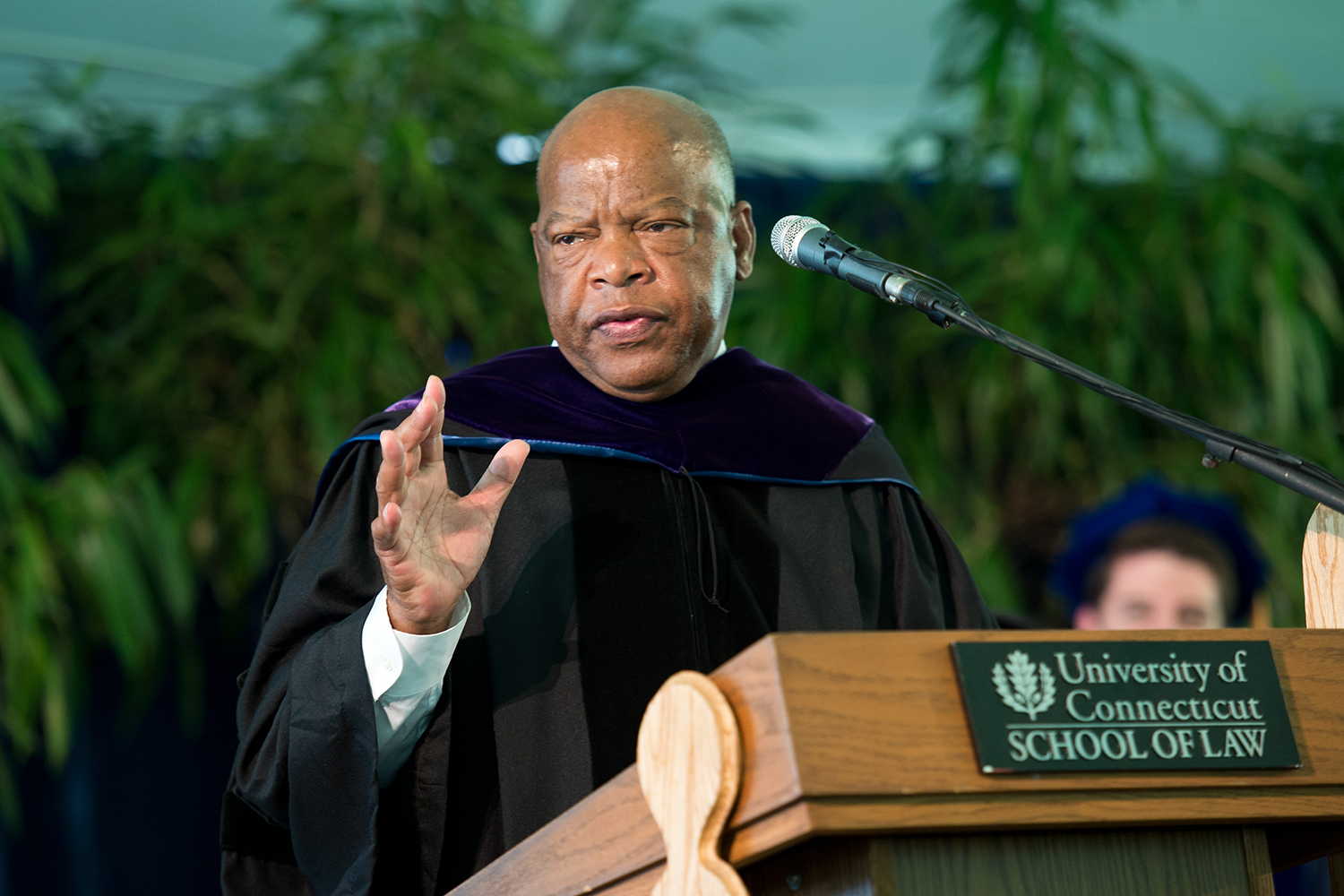

On May 20, 2012, U.S. Rep. John Lewis delivered the commencement address at the University of Connecticut School of Law and received an honorary Doctor of Laws degree.

Transcript: Members of the Board of Trustees, Dean Paul, distinguished faculty, parents, family and friends, and to my colleague, my friend and brother, Congressman John Larson, your congressperson. And to so many others that are here. One young man that I got to know so well like so many others that came from this state, Jack Chatfield, just sitting right here. Good to see you, Jack, and thank you for coming to the South.

You’re a beautiful, wonderful class. You’re beautiful. You’re handsome. You just look good, and I know you’re very smart. I am honored and delighted to be with you on this very special and important occasion. Now this is a long way, to be here in Connecticut. It’s a long way from rural Pike County, Alabama. So, I want to take time to give a special word of thanks to Alice Bruno, the first woman to head the Connecticut Bar Association. Who I understand played a major role in getting me here this morning. Thank you, Alice. Madame President, I listen to women because my mother, my three sisters, my wife, and my aunts, they tell me what to do. And I listen, I respond.

I used to ask my mother, my father, my grandparents, and my great-grandparents a lot of questions. Why? Why? They would say, “That’s the way it is. Don’t get in the way. Don’t get in trouble.” But many years ago, I made up my mind to get in trouble. It was good trouble. It was necessary trouble.

So to each and every one of you receiving a degree today, congratulations! This is your day, enjoy it. Take a deep, long breath and take it all in. But tomorrow you must be prepared to roll up your sleeves, because the world is waiting for talented men and women to lead it to a better place.

Now, when I was growing up outside of Troy, Alabama, about 50 miles from Montgomery, my father had saved $300. He had been a sharecropper, a tenant farmer. But with the $300, he bought 110 acres of land. My family still owns this land today. On this farm we raised a lot of cotton, and corn, peanuts, hogs, cows, and chickens. John Larson will tell you that if you come to my congressional office on Capitol Hill in Washington, the moment you walk through the door, the first thing your staff will offer you will be a Coca-Cola. Because Atlanta is the home of the Coca-Cola company, And Coca-Cola provides all members of the Georgia congressional delegation with an adequate supply of Coca-Cola products. The next thing the staff will offer you would be some peanuts. Like in Alabama, in the State of Georgia we raise a lot of peanuts. I don’t eat too many of those peanuts. I ate so many peanuts when I was growing up, I just don’t want to see any more peanuts. Sometime I would get on a flight flying from Atlanta to Washington, or from Washington back to Atlanta, and the flight attendant tried to give me some peanuts, and I said “No thank you. I don’t care for any peanuts.”

Now on this farm we raised a lot of chickens. Now I want to ask you as law students, law professors: do you know anything about raising chickens? Some of you know something about Popeyes, maybe Kentucky Fried, maybe it’s Chick-fil-A, Bojangles. What else do you have in Connecticut, John? That’s all the chicken? Well, on the farm it was my responsibility to raise the chickens. And I fell in love with raising chickens, like no one else, to raise chickens. As a little boy, I became very good. Take the fresh eggs, mark them with a pencil, place them under the sitting hen and wait for three long weeks for the little chicks to hatch. I know some of you smart law students, and maybe some of your professors, are saying, “Now John Lewis why do you mark those fresh eggs with a pencil before you place them under the sitting hen?” Well, from time to time another hen would get on the same nest, and there would be some more eggs. You have to be able to tell the fresh eggs from the eggs that were already under the sitting hen. Do you follow me? If you don’t follow me that’s okay, that’s okay.

When these little chicks would hatch, I would fool the sitting hen, I would cheat on the sitting hens. I would take those little chicks, put them in a box with a lantern, raise them on their own. Or give them to another hen, get some more fresh eggs, mark them with a pencil, place them under the sitting hen and encourage the sitting hen to sit on their nest for another three weeks. I kept on fooling and cheating on these sitting hens. it was not the right thing to do, it was not the moral thing to do, it was not the most loving thing to do, it was not the most non-violent thing to do, it was not the legal thing to do, it was not the right thing to do. But I was never quite able to save $18.98 to order the most inexpensive incubator, hatcher from the Sears & Roebuck store. Now here in Hartford, in Connecticut, you know what they think about their Sears & Roebuck catalog? That big book, thick book, heavy book, some people call it the ordering book, other people call it the wish book: I wish I had that, I wish I had this. So, I just kept on cheating.

As a young child, I wanted to be a minister. I wanted to preach the Gospel. So, from time to time, with the help of my brothers and sisters and my first cousins, we would gather all of our chickens together in the chicken yard. And along with my brothers and sisters and first cousins that would line the outside of the chicken yard, they would help make up the audience, the congregation. And I was doing speaking and preaching, and some of these chickens would bow their heads, some of the chicken would shake their heads. They never quite said “amen,” but I’m convinced that some of those chickens that I preached to during the ’40s and the ’50s tended to listen to me much better than some of my colleagues listen to me today in the Congress. As a matter of fact, some of those chickens were just a little more productive. At least they produced eggs. Well, that’s enough of that.

When we were visiting the little town of Troy, visiting Montgomery, visiting Tuskegee, visiting Birmingham, I saw those signs that said “white men,” “colored men,” “white women,” “colored women,” “white waiting,” “colored waiting.” As a young child, I tasted the bitter fruits of segregation and racism, and I didn’t like it. That’s why I kept asking those questions. They told me not to get in trouble, not to get in the way. But one day in 1955, at the age of 15 in the 10th grade, I heard about Rosa Parks. I heard the words of Martin Luther King, Jr. on the radio, and I was inspired. At the age of 17, I met Rosa Parks. The next year, at the age of 18, I met Martin Luther King, Jr. I got in the way. I got in trouble. Good trouble. Necessary trouble. So I appeal to you as you leave this wonderful, this great and historic law school: Go out there and get in trouble, good trouble. Make some noise, stand up, speak up, speak out, and fight the good fight.

Sometimes, sometimes, I think in America that we’re losing our way. But we must not lose that sense of hope and get lost in a sea of despair. We must keep the faith. We must stand up, speak up. Another generation of young people, another generation of lawyers came south. Many people came from this state. My seatmate on that Greyhound bus that left Washington, D.C., on May 4th 1961 was a young man from Connecticut, from Mystic, named Albert Bigelow. When we arrived in Rock Hill, South Carolina, only about 35 miles from Charlotte testing a decision of the United States Supreme Court banning discrimination and segregation in intra-state travel we started into a waiting room marked “white waiting,” and a group of young men came up on us and beat us and left us lying in a pool of blood. We didn’t give up. The local authorities came up and wanted to know whether we wanted to press charges. We said, “No, we believe in peace, we believe in love, we believe in non-violence.”

In ’09, February ’09, a month after President Barack Obama had been inaugurated, one of the same young men that had beaten me and my seatmate came to my office and said, “John Lewis, I’m one of the individuals that beat you on May 9th, 1961 at the Greyhound bus station. I want to apologize.” His young son had been telling him over and over, “Search out the people that you’ve beaten.” His son came with him. He gave me a hug. He started crying, his son started crying. I told him I accepted his apology, it was okay. I cried. The three of us cried together. Since then, I’ve seen this gentleman four other times. He called me brother and I called him brother. That is the power of the philosophy and the discipline of non-violence.

Under the rule of law, we have witnessed a non-violent revolution. A revolution of values, a revolution of ideas. We are a better people, we are a better country. And when someone says to me, “Nothing has changed,” I feel like saying, “Come and walk in my shoes.” The signs that I saw, those signs are gone. They will not return. The only place where you’ll see those signs in days to come will be in a museum, in a book on a video. We, as a nation, as a people, are in the process of laying down the burden of race, the burden of class and hate, we’re moving toward the creation of a beloved community.

I say to you again, just think in another period about young people, young students, young lawyers, and lawyers not so young who put their bodies on the line to redeem the soul of America. The homes of lawyers in the South were bombed. In Nashville, in Birmingham, lawyers were beaten for standing up for what is right and just, for defending the most vulnerable people in our society. It is my hope and my prayer as you go out there and get in the way and make trouble, necessary trouble, you will not be beaten. Or jailed. But you will continue the long march toward the redemption of our society.

Just think, a few short years ago, in 11 states of the old confederacy it was almost impossible for people of color to register to vote. The State of Mississippi in 1964/1965 had a black voting age population of more than 450,000 and only about 16,000 registered to vote. One county in Alabama between Selma and Montgomery, Lowndes County, more than 80 percent African-American, and not a single registered African-American voter. People were asked to pay a poll tax. One man was asked to count the number of bubbles in a bar of soap. On another occasion, a man was asked to count the number of jelly beans in a jar. There were African-American lawyers, doctors, and teachers, college professors being told they could not read or write well enough. We had to change that.

During the summer of 1964, three young men that I knew, Andy Goodman, Michael Schwerner and James Chaney, two young white men, one young African-American man, went out on Sunday night, June 21st, 1964, to investigate the burning of an African-American church to be used for voter registration workshops. They were stopped by the sheriff, taken to jail, and later that night they were taken from jail and turned over to the Klan, where they were beaten, shot and killed. These three young men didn’t die in Vietnam. They didn’t die in the Middle East or Eastern Europe or in Africa or Central or South America. They died right here. In our own country, trying to help create a more perfect union.

So, I say to you as you leave here, you have a legacy to uphold. You must make some noise. You must be a headlight, another taillight. You have an obligation, a mission and a mandate to get in the way. Yes, I did get arrested 40 times during the ’60s, and wonderful lawyers got me out of jail every single time. I feel blessed. Not lucky but blessed. But I don’t have any, I don’t have a record. Most of those trumped-up charges were trying to slow down the wheels of progress. It’s my hope and prayer that you will not get arrested or be thrown in jail. But do what you must to create the beloved community. With the law, and with the power of the philosophy and the discipline of non-violence, we can create an American community at peace with itself. We can redeem the soul of America, and in doing so we can emerge as a model for the rest of the world. We’re all in this thing together. We all live in the same house. It doesn’t matter whether we are Black or white, Latino, Asian-American or Native American. It doesn’t matter whether we are straight or gay. We’re one people. We’re one family. We’re one house. We all live in the same house. Not just the house of Connecticut or Georgia or Alabama or California or New York. The American house. The world house.

I’m going to tell you one little story and then I’ll be finished. When I was growing up outside of Troy, Alabama, 50 miles from Montgomery, I had an aunt by the name of Seneva, and my Aunt Seneva lived in what we call a shotgun house. I know what i’m talking about because I was born in a shotgun house. My Aunt Seneva didn’t have a green, manicured lawn. She had a simple, plain, dirt yard. And sometimes at night you could look up through the holes in the ceiling, through the holes in the tin roof and count the stars. Whenever it rained she would get a pail, a bucket or a tub and catch the rainwater. I know here in Hartford, here in Connecticut, here in New England, you’ve never seen a shotgun. In a non-violent sense, a shotgun house, old house, one way in, one way out, where you can bounce a basketball through the front door and it will go straight out the back door. From time to time, my Aunt Seneva would walk out into the woods and cut branches from a dogwood tree and tie those branches together and she would make a broom. And she called that broom the breast broom. And she would sweep this big yard very clean, sometimes two and three times a week, but especially on a Friday or Saturday. She wanted that dirt yard to look very good during the weekend.

But one Saturday afternoon, a group of my brothers and sisters and a few of my first cousins, about 12 or 15 of us young children, were playing in my Aunt Seneva’s dirt yard. And an unbelievable storm came up. The wind started blowing, the thunderstorm rolling, that lightning started flashing and the rain started beating on the tin roof of this old shotgun house. Aunt Seneva got us all inside and told us to hold hands. And we did as we were told. The wind continued to blow, the thunder continued to roll, the lightning continued to flash and the rain continued to beat on the tin roof of this old shotgun house. And my Aunt Seneva cried and kept crying and we all started crying. And then one corner of this old house appeared to be lifting from its foundation. She had us walk to that corner to try to hold the house down with our little bodies. When the other corner appeared to be lifting, she had us to walk to that side. We were little children walking with the wind, but we never, ever left the house.

The wind may blow. The thunder may roll. The lightning may flash and the rain may beat on our old house. Call it a house of the School of Law of the University of Connecticut. Call it the American house. Call it the world house. We all live in the same house. Maybe our foremothers and our forefathers all came to this great land in different ships, but we’re all in the same boat now. We got to look out for each other, care for each other and work and struggle together to build a land that is free of hunger, a land that is free of violence and hate. Can we just get along? Is there something in the water we drink? Is there something in the food that we eat? Is there something in the air that we breathe that makes it impossible for us to live like humans? Can you use the law as an instrument, as a tool to take us to a higher plane?

I say, my young friends, use the law. As you use the law, walk with the wind. And let the spirit of this university and law school be your guide. Thank you very much.