What animal has grappling hooks on its anterior end, a stomach on the outside of its body, and can tell us a lot about evolution? That would be the tapeworm.

As a result of a recent large-scale global survey, tapeworms, a class which encompasses more than 5,000 species, are now one of the most well-known groups of multi-cellular parasites. But that project raised intriguing questions regarding the evolution and classification of these organisms. Perhaps most importantly, it revealed the remarkably central role tapeworms that use elasmobranchs (i.e., sharks and stingrays) as hosts appear to have played in the evolutionary history of the group.

University of Connecticut Board of Trustees Distinguished Professor of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology Janine Caira, and her colleagues Elizabeth Jockusch and Jill Wegrzyn at UConn, and UConn alumna Kirsten Jensen, now on the faculty of the University of Kansas, have received a $1.5 million grant from the National Science Foundation to tackle some of the questions raised by the team’s earlier survey work. The generation of a robust phylogenetic framework for the major lineages of tapeworms is a key interest for the group; the researchers then hope to use this “backbone” to revise the higher classifications of the group.

The focus of the grant will be on the remarkably diverse tapeworms of sharks and stingrays (elasmobranchs). Of the 19 major lineages of tapeworms currently recognized, nine parasitize elasmobranchs. However the team’s recent survey work indicates that the tapeworms of elasmobranchs may represent as many as 10 additional independent major lineages, at some of which are more closely related to the tapeworms of birds, mammals, and bony fish than they are to other groups of elasmobranch tapeworms, raising some fascinating evolutionary questions.

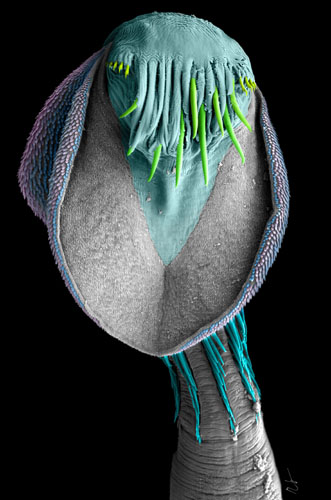

To generate the evolutionary tree, Caira and her team will use a targeted gene capture approach to identify hundreds of new genes that they will then sequence for about 1,000 species of tapeworms. They will also use morphological data from light and scanning electron microscopy to study the physical characteristics of many of these species. In combination, genetic and morphological similarities will allow Caira and her team to better understand the evolutionary relationships among the tapeworms overall.

“This project will help to fill the gaps in the approximately 200 million years of evolution separating these lineages,” Caira says.

The project will also expand on preliminary genomic resources the team developed for tapeworms of elasmobranchs that will serve to complement genomic resources generated by other workers for the two major groups of tapeworms that parasitize humans. In combination, these resources span the taxonomic diversity of all tapeworms, enabling Caira and her team to address broad-scale questions about the evolution of parasitism in this group.

With a “backbone” in hand, Caira and her team will use genomic analyses to look for signatures of parallel molecular evolution in what appear to be multiple instances of transitions from elasmobranchs to bony fish and from the marine environment to the freshwater environment in unrelated groups of tapeworms. This work is aimed at providing some insight into the environmental factors that affect parasite evolution overall.

“This allows for much more robust inferences about ancestral states, gene gain and loss, and the dynamics of genome maintenance and functional integrity in extremely diverse selective environments than is possible with current data,” Caira says.

The project also aims to help disseminate information on tapeworms to as wide a spectrum of audiences as possible. The Global Cestode Database, which is a public resource designed to allow anyone to search for information about tapeworms, will be updated. An online key to the major groups of tapeworms, reflecting the revised classification resulting from the project, will be created. An online version of the prototype of an interactive children’s book about tapeworms, titled “Meet the Suckers” will also be developed.

Janine Caira earned her Ph.D. in parasitology at the University of Nebraska at Lincoln. Her research focuses on morphology, taxonomy, systematics, and the evolution of platyhelminths, especially tapeworms of sharks and stingrays.