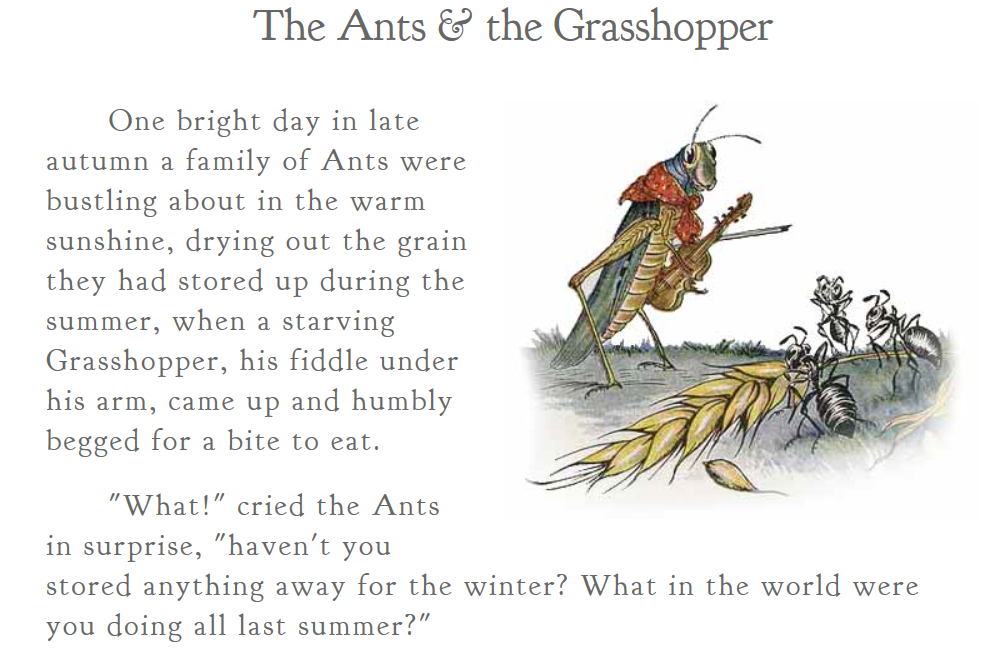

In one of Aesop’s famous fables, we are introduced to the grasshopper and the ant, whose decisions about how to spend their time affect their lives and future. The jovial grasshopper has a blast all summer singing and playing, while the dutiful ant toils away preparing for the winter.

Findings in a recent publication by UConn psychology researcher Susan Zhu and colleagues add to a growing body of evidence that, although it may seem less appealing, the ant’s gratification-delaying strategy should not be viewed in a negative light.

“This decision strategy can be harder or more time-consuming in the moment, but it appears to have the best outcome in the long run, even if it isn’t fun,” says Zhu.

The ant is what the researchers would call a maximizer. A maximizer is someone who makes decisions that they expect will impact themselves and others most favorably: they seek to “maximize” the positive and make the best choices imaginable. Yet the ant may consider so many variables that the same tendency to maximize benefit may lead to difficulty in making decisions. Previous research suggested this, with maximizers being less happy overall, having higher stress levels, and possibly regretting decisions they made.

Zhu suggests that maximizing has beneficial consequences.

“Maximizers are forward thinking, conscientious, optimistic, and satisfied,” she says. “Though a lot of work and thought go into those decisions, maximizing has beneficial outcomes.”

Surviving the winter perhaps?

On the other end of the spectrum, the grasshopper is more of what researchers might refer to as a satisficer (satisfy plus suffice = satisfice), or someone who will be happy with things being “good enough,” who tends to opt for instant gratification and tends to live moment to moment.

“A satisficer will make a decision, feel good about making it, and move on,” says Zhu.

The ant and the grasshopper are of course extreme examples of each dispositional type, and most people exhibit both qualities. “There tends to be a bell curve and most people fall towards the middle and exhibit aspects of both tendencies,” Zhu says.

To conduct the study, the researchers used Amazon’s Mechanical Turk or MTurk service, where their survey was given to hundreds of participants, generating a pool of data.

Survey takers were asked questions regarding financial decisions, namely savings habits and tendencies. They rated various statements, such as “I never settle for second best,” on a five-point scale from strongly agree to strongly disagree. The questionnaire was designed to gauge whether participants tended to maximize their decisions, how they felt their decisions would impact the future, and how they viewed smaller immediate rewards or larger future rewards.

The survey also looked at how participants expected their decisions to affect the future. They were asked to rate statements like, “I consider how things might be in the future and try to influence those things with my day to day behavior,” and “I often think about saving money for the future,” and to provide information about lifetime savings amounts and current income.

“What we are measuring are tendencies,” says Zhu. “When we ask what people tend to do, they’re pretty stable and can be pretty good predictors for actual behavior.”

Once data was gathered, researchers crunched the numbers and observed trends. With maximizers, the data suggested a positive relationship with their future-oriented thinking, better money-saving habits, and concern for the future of others.

The main takeaway? Zhu says, “Maximizing can be a good thing. Previous research looked at decision-making difficulty and other negative outcomes, and that added a negative connotation to maximizing tendencies. We’re trying to frame it in light of the high standards and the beneficial outcomes, to help reshape the view of maximizing.”

No matter where you fall on the spectrum, take advice from both the forward thinking ant and the fun-loving grasshopper. Plan for the future, but also have some fun now.