Teen suicide is a tragedy, but like many tragedies, it strikes some areas more frequently than others. To find out why, UConn researchers mapped teen suicide attempts across the state. Their results are in press in the Journal of Adolescent Health. They reveal some surprising variation in risk across communities, and may provide insight into suicide prevention tactics that work.

Suicide is the second leading cause of death among people aged 15-24 years, with 12.5 youths per every 100,000 killing themselves in 2013, according to the Centers for Disease Control. Community demographics and socioeconomics play a part in the risk. But some disadvantaged communities have far fewer teen suicides than their demography would predict, and some affluent communities have far more.

“Can we learn from districts that are doing well, and apply those lessons to those that are struggling?” UConn medical sociologist and chair of behavioral sciences and community health Rob Aseltine wondered. First he had to identify communities that were truly doing better than the norm. There was no cookbook way to do it; a small, affluent community might have very few adolescent suicides simply because there are very few teens in the community, or because those that there are have very good access to healthcare, or because the community does a good job at suicide prevention. So he teamed up with UConn statistician Kun Chen to figure out the best approach.

Can we learn from districts that are doing well, and apply those lessons to those that are struggling? — Rob Aseltine

Instead of counting actual suicides, the two researchers decided to focus on the rate of attempted suicide instead. Hospitals record such events in medical claims and electronic health records, and they are much more common than actual suicides. And attempts are major medical events in and of themselves, requiring an average hospital stay of five days.

“People are doing themselves serious damage,” Aseltine says.

The team compiled numbers of suicide attempts of 15-19 year olds in every school district in the state. They then adjusted for 10 community characteristics, such as average household income, racial and ethnic diversity, and number of parents in the home.

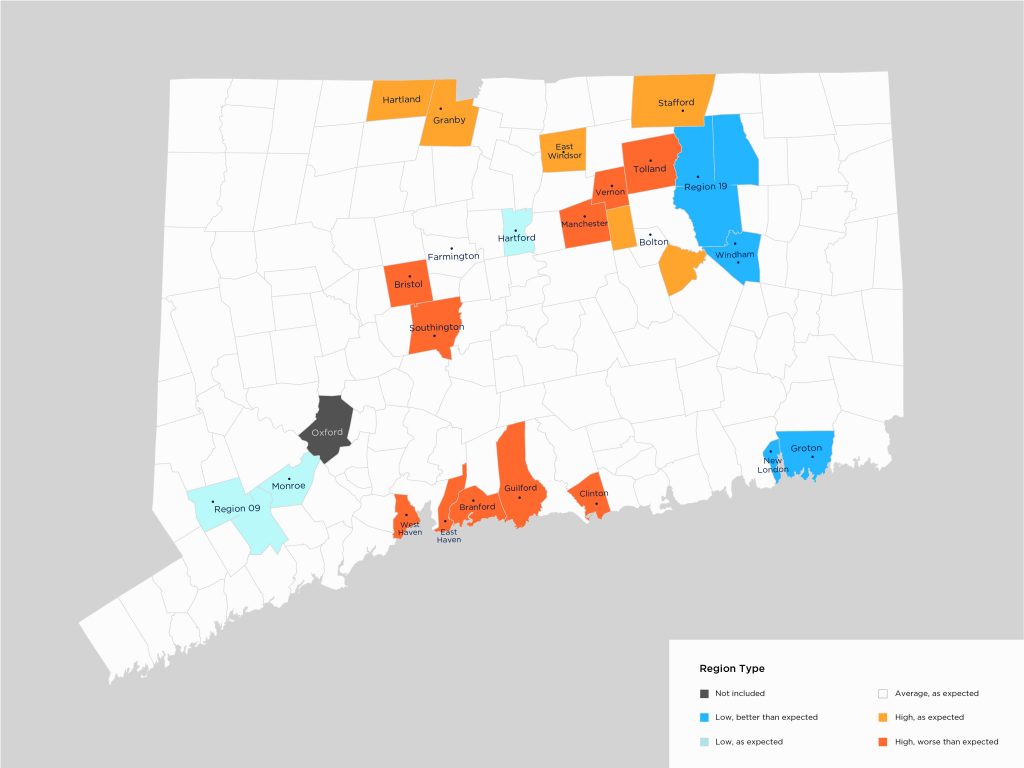

They found 10 districts in Connecticut with significantly higher risk for suicidal behavior among adolescents. These communities had rates 154 percent to 241 percent higher than expected. More heartening, they found four districts with significantly lower risk for suicide attempts than anticipated (see map). Two of these communities – Windham and New London – stood out in particular. They are two of the five poorest communities in the state, yet had attempted suicide rates that were approximately half of what would be expected given their community resources.

This is the first time Connecticut has ever looked at this type of data, and Connecticut is one of the more organized states when it comes to preventing teen suicide, Aseltine says. He hopes other states will be able to make good use of the same technique in the future.

“This is a novel and promising approach with implications for our ability to prevent suicide-related outcomes. The study illustrates the potential benefit of establishing public health surveillance systems using administrative data, often an untapped resource, to address these critical public health issues,” says Damion Grasso, a professor of psychiatry at UConn Health who was not involved in the research.

Aseltine and Chen’s work was supported by a grant from the federal Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration’s Garrett Lee Smith program. The Connecticut Department of Mental Health and Addiction Services has awarded Aseltine and his colleagues additional funding to follow up on the results and figure out why the anomalous communities have lower rates of attempted suicides. Some of it may be suicide prevention programs, but other reasons may be community characteristics that are harder to influence. For example, school district 19, which includes E.O. Smith High School in Storrs, also had fewer attempts than would be statistically predicted. That district, which encompasses the area around UConn’s main campus, has an active community life and higher-than-average levels of education among the local adults, which may help inoculate teens against suicide.

But another message can be garnered from the data as well: the majority of suicide attempts are typically made by individuals already involved in the mental health care system.

“They may be receiving psychiatric care, but their risk of suicide is not recognized,” Aseltine says. More proactive help for teens struggling with depression and other mental health issues is an obvious first step.

Aseltine and his colleagues have recently been notified by the NIH that they will receive a grant as part of the national Zero Suicide initiative to reduce suicides among patients in the health care system.