A preview from the upcoming edition of UConn Magazine, coming in June. For Magazine stories in the current and earlier editions, visit magazine.uconn.edu/ .

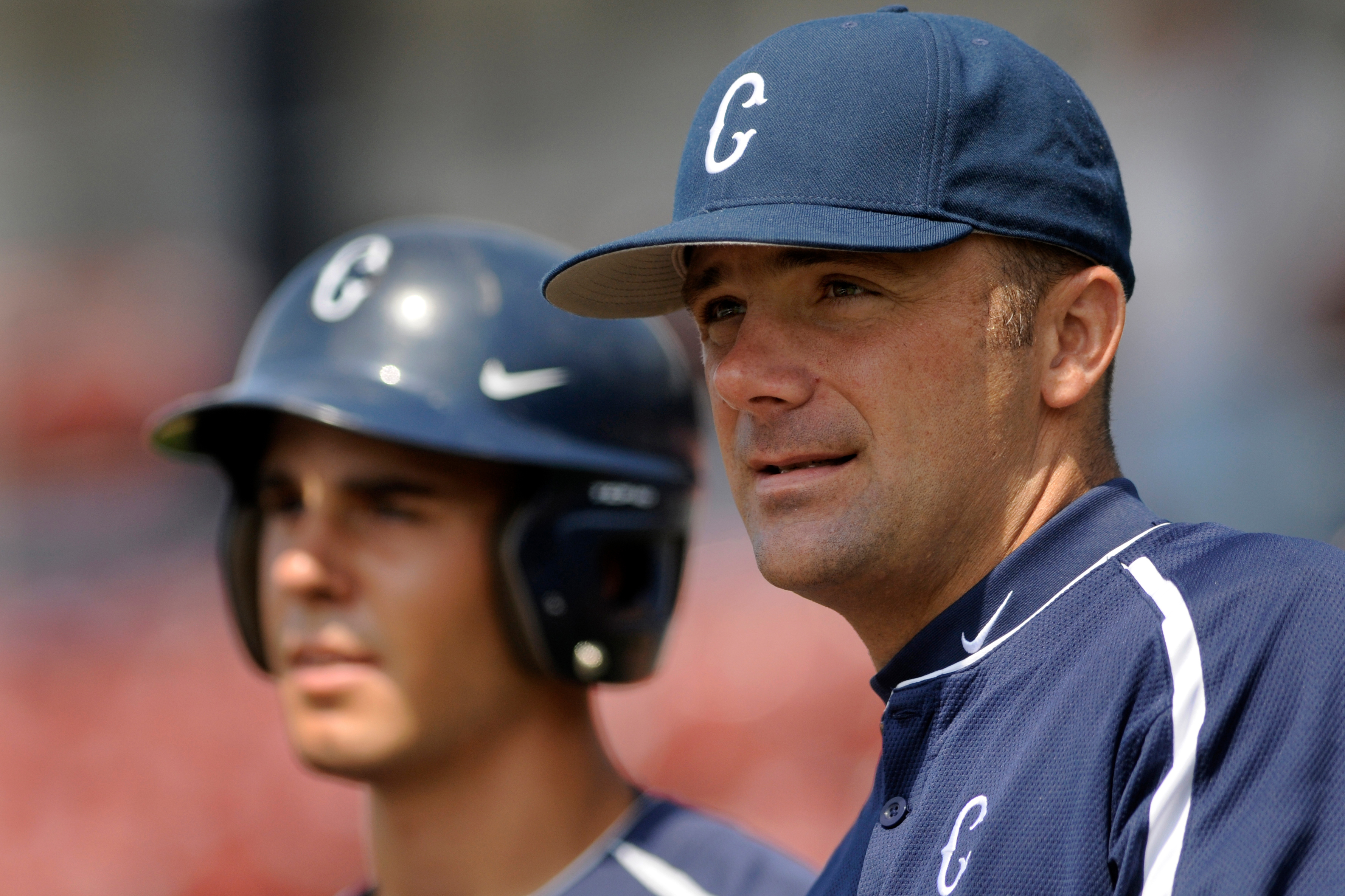

Cold-weather baseball teams aren’t supposed to have the kind of success Jim F. Penders ’94 (CLAS), ’98 MA has had in his 15 seasons as head coach of the Huskies. It’s in his DNA, other coaches insist – and they may be right.

His father, Jim E. ’66 (ED), a four-time championship high school baseball coach and national coach of the year at East Catholic High School in Manchester, Connecticut, and his uncle, Tom ’67 (BUS), who would coach four different Division I teams to the NCAA Basketball Tournament, played together on the Huskies’ 1965 College World Series team. His paternal grandfather, Jim W., was the longtime championship baseball coach, with four state titles, at Stratford (Connecticut) High School, where the playing field at Longbrook Park now bears his name. In the 1930s, Penders Jr.’s maternal grandfather, Sal Cholko, was a catcher for the state’s American Legion Baseball championship team and later played in the Bridgeport Industrial League. And his brother, Rob, serves as the baseball coach at Division II St. Edwards University in Austin, Texas.

This impressive lineage makes Jim F. Penders a lifer, a characterization considered high tribute in a sport that began in its modern form in the mid-19th century and was described by the poet Walt Whitman as “our game – the American game.”

Now in his 14th season as the Huskies’ head coach, Penders will have been part of UConn baseball for 25 of the past 27 years – as a student-athlete, assistant coach, then head coach. He is a four-time conference Coach of the Year who has led the Huskies to 30 or more wins in 11 of 13 seasons, while developing 39 players either drafted or signed by professional baseball teams – including nine who have won All-America honors.

In 2016, the Huskies won their first American Athletic Conference title and made their fourth NCAA Tournament appearance in the past seven seasons, despite being a cold-weather team competing against conference opponents based in primarily warm-weather locations. Penders’ record of 477-337-4 is second only to that of his mentor, Andy Baylock (556-492-8), who coached all of the Penders men during his long career as the Huskies’ head coach.

Drawn Into Coaching

Penders’ earliest memory is, naturally, one of baseball. He was 3 years old, and his father’s East Catholic team had just won its first state championship at Yale Field in New Haven. Someone boosted young Jim over the fence so that he could run to hug his father, but by the time he was over the fence, the team had hoisted the elder Penders up in celebration and were carrying him away. “I was crying my eyes out, wondering where they were taking my Daddy,” he says. “It was traumatic, and I remember it clearly.”

Better memories began to take shape as Penders started to play the game himself. He and his younger brothers, Mike and Rob, organized neighborhood Wiffle Ball games in the backyard of their home in Vernon. They made a field by putting up fences, foul lines, and a scoreboard, even improvising a public address system to announce the game using walkie-talkies. After East Catholic games, where they served as batboys, the Penders boys would quickly move onto Eagle Field and run around the base path, while their father took down the American flag before speaking with news reporters.

And though there were always used bats, balls, and gloves around the Penders house, the coach living there never put pressure on his boys to play the sport.

Penders doesn’t remember his father giving him any instruction in the game of baseball until he was his player as a freshman in high school.

“He made his sons seekers by not shoving it down our throats. We always emulated him, wanted to please him, but it was never that push. He told us to study and do well in the classroom. That’s where he pushed us, but never in athletics,” says Penders.

He says he couldn’t help but want to pursue the game, because his dad’s former players would show up at their house. “I think that drew me eventually into coaching.”

A greater baseball influence on the 8-year-old Jim would be his grandfather, Sal Cholko, whose photo – in a catcher’s crouch holding up a glove – sits on Penders’ desk alongside images of the elder Penders men during their playing days, surrounded by baseball memorabilia on the walls and shelves in his office. During summers, when the Penders boys visited their grandparents in Stratford, there would be a game of catch in the backyard; Cholko would turn young Jim’s hat around, as a catcher would do in order to put on a mask. Later, when the young Penders tried out for an instructional league team, one of the coaches asked who wanted to be a catcher. “No hands went up,” Penders recalls. “I figured I’d get to play if I raised my hand. I liked getting dressed in the gear.”

An all-state catcher at East Catholic, where he also served as senior class president, Penders went on to become a four-year letter winner for the Huskies and a co-captain for the squad that won the Big East Conference tournament. He played in the NCAA championships his junior and senior years, and earned First Team All-Northeast, All-New England, and All-Big East honors during his senior season, when he hit .354 with seven home runs and 46 runs batted in.

Between his junior and senior years, Penders served as an intern for U.S. Rep. Sam Gejdenson of Connecticut and, after graduating with a degree in political science, he returned to Washington, D.C., to work as a political fundraiser for U.S. Sen. Tom Harkin of Iowa. During that time, he met President Clinton. However, he soon found himself thinking about baseball.

“I was feeling a pull to do what my dad did,” says Penders. “I always use the line from ‘Godfather III’: ‘Just when I thought I was out, they pull me back in.’”

He called his former coach, Baylock, asking whether he could be a graduate assistant coach. Baylock knew the family coaching history, had coached Penders’ father and uncle, and recognized Penders’ commitment to academics. “On my teams, if you made Dean’s List, you got a steak dinner at my house,” Baylock says. “He was always at the dinner table.”

The timing turned out to be right, as part-time UConn assistant coach Marek Drabinski ’90 (BUS), ’94 MA, who played two years in the Atlanta Braves organization, had just been hired as head coach at Brown. Penders returned to Storrs as a graduate assistant coach while pursuing a master’s degree in education. Two years later, he became the Huskies’ first full-time assistant baseball coach.

For the next seven years, Penders recruited student-athletes, served as hitting coach, and worked with catchers and outfielders. When Baylock decided to step down as head coach in 2003, Penders moved to the next seat over on the dugout bench.

“Like they say, moving over 12 inches on the bench is a giant leap – realizing you don’t know everything that the head coach does until you had to do it,” Penders says. “That first year, in December, I’m thinking, what am I supposed to be doing today? It was trial and error, having to have my antenna up on everything, realizing the buck stops with you.”

A Winning Philosophy

He knew there would be mistakes to learn from, none more memorable than in Jacksonville, Florida, during one of his first road trips as head coach. Preparing to play against Ohio State, a Top 25 team that year, Penders set his two lineup cards – one for a right-handed pitcher and another for a left-handed pitcher. Former Huskies baseball player Delroy Parkinson ’87 (BUS), ’93 MBA, who lives in the area, stopped by for a short conversation, just before Penders learned that the Huskies would face a right-hander. Penders gave a lineup card to the umpire, and the game started.

The Huskies scored on a two-run double in the first inning when the Ohio State coach walked out to home plate and began talking with the umpire. Penders had handed the umpire the batting order for the left-handed pitcher, sending up batters in the incorrect order according to the official lineup card. The runs would not count, and the inning was over. The Huskies quickly took the field so that Ohio State could bat.

“I learned in that instant: You have to be accountable,” Penders says. “I felt as alone as I’ve ever been in the dugout while they ran out on the field. I gathered them as quickly as possible, looked them all in the eye, and said, ‘I really screwed up. It’s all my fault. It will never, ever happen again.’ They said, ‘We got your back, Coach.’ We lost in the 10th inning, but after that, we won eight straight, and it finished a great trip. To this day, I’ll go over the lineup line-by-line in the dugout.”

Penders has turned such hard-won lessons into a coaching philosophy his student-athletes know as ACE – Attention, Concentration, and Effort — that has resulted in five former Huskies currently on the rosters of Major League Baseball teams and five in the minor leagues.

“When Jim talks to a player, it’s not just to make him feel good today. If he thinks the player is slighting himself, he lets them know,” says Josh MacDonald ’06 (CLAS), Huskies pitching coach and recruiting coordinator since 2012. “We don’t have palm trees up here, and we play in one of the toughest conferences in the country. I think that’s why you see our guys doing really well.”

Justin Blood, who spent six years as the Huskies pitching coach under Penders before moving on to become head coach at the University of Hartford, says Penders is a program builder. “He wants the student-athletes to understand that the program is bigger than them. The kids hear the same message from him over and over again. They respect it and live by it.”

The motivational speeches Penders delivers can also result in some memorable events, such as the one several former Husky players recount from Florida during the Big East Conference Tournament after Penders was named Coach of the Year. As the team bus was heading back to the hotel, the head coach told the driver to stop on the small bridge they were crossing. He stood at the front of the bus, holding up the trophy he had just received and said, “I don’t give a [expletive] about this award! I want the trophy that says we won the tournament!” He then got off the bus and threw the trophy into the water, breaking up the bus into laughter.

“There was always an expectation to win and to give everything you had,” says Matt Barnes ’11 (CLAS), now a pitcher for the Boston Red Sox. Barnes is one of several former Huskies who returned to Connecticut for the annual pre-season baseball dinner in January to talk with current members of the baseball team about their shared experience under Penders. “We adopted the philosophy of paying attention to the little things; that’s what separated us from a lot of people. It wasn’t just on the baseball field. It was in the weight room, running, making sure you had everybody’s back. Doing things the right way and working hard. Those were the ingrained philosophies.”

Adds Willy Yahn ’18 (CLAS), third baseman and a co-captain for this year’s squad: “You know they appreciate what Coach Penders and the program did for them, not just as a baseball player but as a man. He always talks about how ‘you can’t fool the man in the mirror.’ You’ve got to be doing the right thing at all times.”

The bond shared among current and former Huskies is strengthened on yet another level: practicing at J.O. Christian Field in Connecticut’s frigid weather in preseason when it is possible, and moving indoors when there is snow on the ground, doesn’t slow them down. In recent years, during extended travel for the American Athletic Conference, UConn vies with competitors who primarily practice in warm-weather climates. “We can hang with all these other teams and beat them while they’re down South working out all the time,” says senior co-captain and second baseman Aaron Hill ’17 (CLAS). “Coach Penders tells us there are no excuses. Having to deal with all those different elements, I take pride in that.”

‘A Real History’

Huskies field hockey coach Nancy Stevens and women’s basketball coach Geno Auriemma, both Hall of Famers in their respective sports, have observed Penders as he has taken the baseball program toward higher levels of success and national recognition.

“Jim has coaching in his DNA,” says Stevens. “His coaching staff and players always represent the University in the best manner possible, and continue to bring pride and honor to the Department of Athletics. Jim does a terrific job of honoring his former coach and mentor, Andy Baylock, through competing for conference championships and post-season success. He is a valued colleague and friend.”

Says Auriemma, “I think Jim might be the best coach working at UConn over the past 15 years when you consider the resources he has and the challenges that inherently exist in this part of the world. To be able to consistently, year after year after year, put together a great baseball program and to produce the number of major leaguers they have, that’s the kind of stuff that’s done in warm-weather states where they play year-round.”

Penders embraces the responsibility of being part of the legacy of both Connecticut’s baseball history and the state’s flagship university. That was evident in 2010, following a loss to the University of Oregon in the first round of the NCAA baseball tournament, which included the Huskies’ first NCAA post-season win since 1979. He began his press conference talking about the history of baseball in Storrs, and the brothers who donated their farmland to begin the agricultural school that would evolve into the University of Connecticut.

“We’re just trying to outwork the opposition,” Penders had said. “We have won more games [48] than any other team that has worn the uniform since 1896. Nobody can take that away. I talked to the guys about Charles and Augustus Storrs. They just wanted to be better farmers. That’s where it started. That’s what it’s got to be about. We’ve got to outwork everybody.”

Penders’ insistence on hard work and accountability is not just for his players; it also is for his coaching staff and, most importantly, himself. He says there is a reminder of that expectation each day when he puts on his baseball uniform, No. 16, to coach his team. Most college athletes choose a uniform number worn by a parent or older sibling, a favorite professional athlete in the sport, or the number they wore in high school. As a UConn freshman, Penders asked to wear No. 15, the number worn by New York Yankees catcher Thurman Munson, his favorite player growing up. Learning it belonged to another Husky player, he asked the veteran equipment manager for any odd number – but nothing with the No. 6, a number he disliked. The next day, he found a uniform hanging in his locker with No. 16 on it.

“The next year, you get to change the number,” Penders says. “I’ve kept it because it’s a daily reminder: Don’t take yourself so seriously; you’re not that important. The program, the University, are a hell of a lot more important than you’ll ever be. My father playing here, my uncle playing here, there’s a real history that’s important to me, and I try not to screw it up. I wear it as a constant reminder of that. No matter how many games we win, you’re still wearing 16, and you’re still that clueless freshman.”