To read more stories from the latest edition of UConn Magazine, go to the Magazine website.

June heat radiated from the nighttime pavement as Glenn Smith ’87 (CLAS) sprinted past the palmettos and live oaks swaying anxiously in the beam of Charleston, S.C., streetlights. His flip-flops smacked the soles of his feet, their harried slapping sound bouncing off the city’s single-style houses and rapidly replacing the rhythm of acoustic guitars and beer-fortified singing that had so recently surrounded him.

Glenn’s wife, Kitty, pulling clothes out of the dryer upstairs, heard his urgent words as he burst in – “Lock the doors and stay inside, the shooter’s still out there.” – and he was gone again, running, as always, toward the danger.

Around the block, people clogged the street before the tall white church, milling, wailing, falling over one another. Police passed, perched with M16s cocked on the hoods of slow-moving cruisers, combing the surrounding streets. A church member said he’d seen Rev. Pinckney being rushed down the steps on a stretcher. The coroner emerged from an arriving truck with four of her deputies.

Smith questioned, scribbled, tweeted, snapped cellphone photos, and finally, hurried to his office by 11 p.m. By 1 a.m., the stories by him and his colleagues were written and the paper went to press only about an hour late; by 7 a.m., it was on Charleston doorsteps. The headline read: Church shooting kills 9 – Manhunt on for suspect after ‘hate crime’ shooting at Emanuel AME.

What began as an evening of music and microbrews with neighborhood friends capped a long year colored by violence for the special projects editor at South Carolina’s largest newspaper, The Post and Courier. Smith’s state had seen unparalleled domestic abuse, fatal police brutality, and now a mass racist killing.

Smith’s determination to run toward scenes of heartbreak such as this is nothing new. What is new is the fact that he has recently been recognized for doing so, for pushing his state to enact reform, and in the process earning a Pulitzer Prize.

A Trustworthy Boy

As a boy in Wethersfield, Conn., Smith spent mornings at the kitchen table, sipping coffee and trading sections of the Hartford Courant with his father. Teenage Smith played classic rock in garage bands, frequented Hartford’s used-music stores, and drew makeshift graphic novels. He was considering a career in art until his father intervened.

“He said, ‘Glenn, you should go into journalism. That’s where the money is,’” Smith chuckles. “He didn’t know a lot about journalism.”

Smith declared a journalism major as a freshman at UConn in 1983. The first article he wrote came back with a failing grade, with big marks off for style. But his second draft earned a B+.

Department head Maureen Croteau saw potential when he began stopping by her office in the journalism department to say hello.

“He had this way of speaking and listening that made you think that you were the most important thing he’d done all day,” she says. “You trusted him implicitly. That’s a great gift for a journalist.”

In his coursework, Smith learned to play with words, to employ description, to look beyond the obvious. He grew interested in people, in culture, and remembers a Hartford Courant series on heroin-addicted prostitutes. Vivid scenes of women shooting up in front of the Capitol dome still linger in his memory.

“It was the greatest thing I had ever read,” he says. “It exposed this incredibly human story that was right before your eyes, but you’d never seen.”

Croteau guided him to an internship at the New Britain Herald that led to his first job as a crime reporter. Smith learned omnivorously about his beats: the Capitol, City Hall, education, police, and minority affairs, and eventually published a few feature stories.

He met Kitty at a Pogues cover band show, and they married in 1996 in a ceremony featuring raucous blues-rock and Cajun bands. Sick of New England winters, and feeling a sense of wanderlust, the couple moved two years later to Charleston, where The Post and Courier hired Smith as a crime reporter.

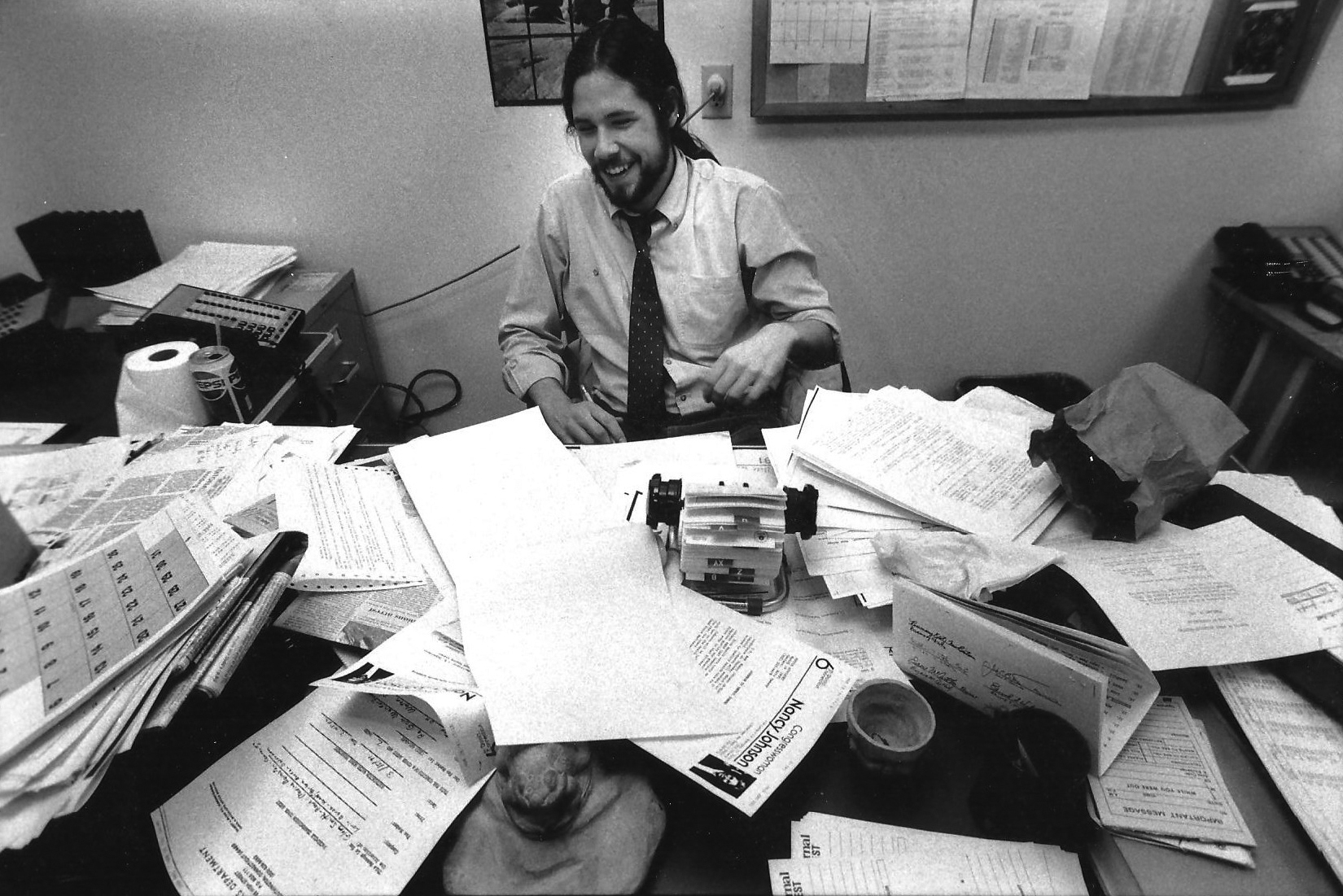

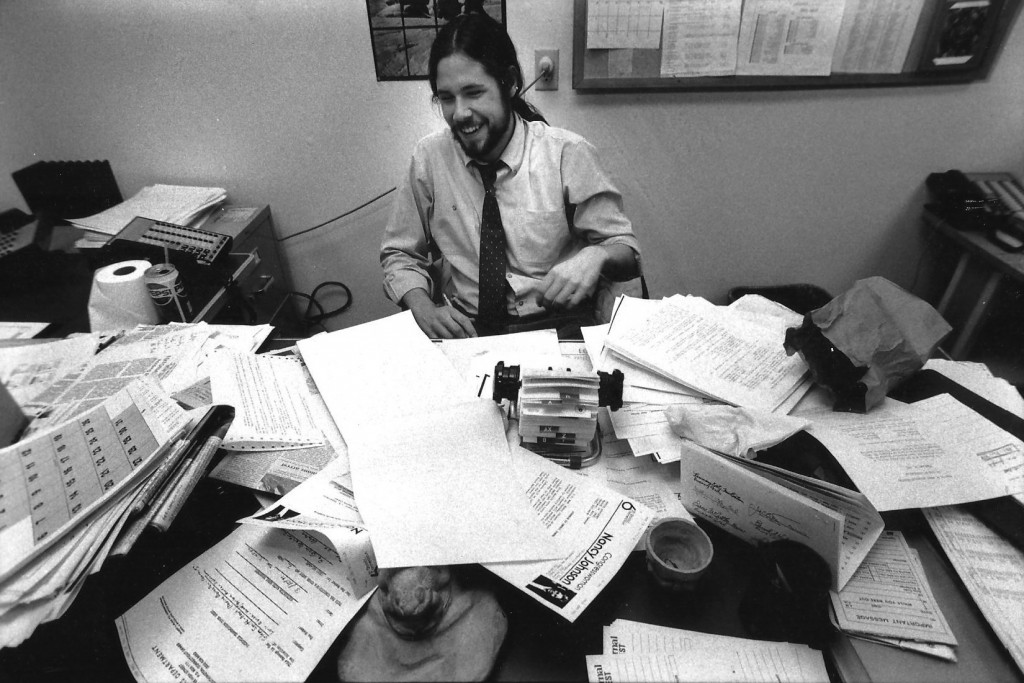

The first thing special projects reporter Doug Pardue noticed about Smith when he arrived at The Post and Courier was Smith’s waist-length, braided ponytail. Pardue was impressed not by its fashion, but by its symbolism.

“To look like that, and to be a cop reporter, it really takes something,” he says. He watched as Smith and his liberal-looking ponytail staunchly pursued the daily crime beat in deeply conservative South Carolina with a measure of quiet curiosity and conviction, building a trustworthy reputation with police and other law enforcement officials.

Pardue would read Smith’s stories and fine-tune them with a feature writer’s eye. Despite an occasionally over-the-top “Dashiell Hammett quality,” he says, Smith had a knack for storytelling, writing “the way people speak.” Before long, the paper realized Smith was wasted on crime reporting, and promoted him to investigative reporter.

A History of Violence

In September 2013, for the third year running, the Violence Policy Center of Washington, D.C. named South Carolina first in the nation for the rate of women killed by men. A domestic violence coalition held a conference call and invited all state news media.

Smith was the only reporter who called. “I wondered, has the state gotten so numb to this that it’s no longer a story?” he recalls.

Now an editor for a team of reporters, Smith says he wanted “to tell this story in a way it hadn’t been told before.” His team spent eight months interviewing domestic abuse survivors, lawmakers, police, and social workers; building databases using police reports, court records and interviews; and plotting details of abusers and their histories on maps.

The investigation, published the following August, revealed that more than 300 women had died at the hands of abusive men in the previous decade, and while a person could serve up to five years for cruelty to a dog, first-offense domestic violence carried a maximum penalty of just 30 days in jail.

The multi-part series, titled “Til Death Do Us Part,” revealed poorly trained police, inadequate punishment, little funding for support programs, and entrenched religious beliefs about marriage, all adding up to a “corrosive stew,” according to Mitch Pugh, The Post and Courier’s editor-in-chief. Dozens of bills had failed in committees in the preceding decade.

“On one side, you have someone being bludgeoned with an axe, and on the other, the legislature is declaring barbecue the state food,” Smith says.

The attorney general pledged that 2014 would be the year for comprehensive domestic violence reform. The legislature cobbled together reform bills, each stalling periodically over controversial provisions, such as gun bans and tiered systems of punishment.

“We were at every remote subcommittee hearing meeting,” says Smith. “We let them know we were watching, and were going to see this to the finish line.”

Over the next six months, he and his colleagues wrote more than 60 follow-up stories, keeping a running tally of the number of people, reportedly 30 by April, who died at the hands of partners while lawmakers debated the details of reform.

Then, on April 4, an unarmed black man was shot dead by a police officer, who claimed self-defense, in North Charleston. Three days later, an anonymous tipper handed Smith a video depicting Officer Michael Slager shooting Walter Scott in the back as he fled a routine traffic stop. The ensuing national outrage redoubled the already massive media presence camped outside North Charleston City Hall.

Smith and his colleagues didn’t sleep much. Times like these, says Smith, are a major reason hometown newspapers exist.

“We’re the local guys, so we needed to get it right,” he says. “We’re the only ones who can tell these stories with the right context, because we live here.”

The Highest Honor

Smith’s team was immersed in a series that would reveal 235 South Carolina police-involved shootings in the previous six years when they paused for an afternoon.

The newsroom was filled with flat-screen TVs, and the chairman of their board and the company president joined the staff around the warren of desks. Nervously eyeing several bottles of champagne, they tuned in to the Pulitzer Prize’s YouTube channel. “Til Death Do Us Part” was nominated in the Public Service category: the most prestigious Pulitzer, and the only one that comes with a gold medal.

“I’d put it out of my mind,” says Smith about the possibility that they might win a Pulitzer. “What hubris it was to think that we had a shot.”

Three minutes into the streaming video, the room erupted.

“It’s one thing to win a Pulitzer at a place where they win them all the time,” says Croteau, alluding to The New York Times and The Washington Post. “This was a Pulitzer won by people at a good newspaper doing a good job because it’s the right thing to do.”

The next month at Columbia University, surrounded by marble and pillars, the Pulitzer committee called the series “riveting” and presented the gold medal to Smith, Pardue, Jennifer Berry Hawes, and Natalie Caula Hauff. Walking out of the luncheon, Mitch Pugh checked Twitter and learned that the General Assembly had finally passed a domestic violence reform bill. Signed into law by Gov. Nikki Haley, the bill stripped abuse offenders of gun rights and strengthened sentences for offenses.

“It was such a moment,” Smith said of hearing that news some 20 minutes after being handed the nation’s highest journalism award. “Absolutely gratifying.”

The Community Pages

Three weeks later, Smith was strumming those old classic rock tunes in a friend’s living room when his phone buzzed. “Get to that church near your house,” his co-worker said. “People are dead.”

Throughout his career, Smith’s focus has been simple: Get it right. Find the facts and tell accurate stories, and do it with sensitivity, humanism, context, and meaning.

In the week following the murder of nine black people at a church prayer circle, many national news organizations focused on the white gunman and his racist manifesto. But on Sunday, June 21, The Post and Courier’s front page had only an image of nine palmetto leaves twisted into roses, with a poem individually memorializing the nine victims.

“These were our neighbors, these were our friends,” says Smith. “They were so much more important than the shooter.”

By some estimates, the trade of journalism has cut 20 percent of its workforce in the past 15 years, and dozens of newspapers have shut their doors. Croteau comments, though, that the Internet has opened up a renaissance in long-form, investigative work.

“Done right, done the way Mr. Smith has done it, it is a noble profession,” she says.

Smith is grateful to have landed “a good gig” at a family-owned newspaper that values telling human stories.

The amount of respect Smith commands in the community is “awesome,” says Pardue. “The kind of dogged, relentless, prying reporting that Glenn is known for has made a substantial difference, time and time again.”

Post-Pulitzer, Smith’s objective is to convince people that he and his team aren’t a “one-trick pony.” Their August 2015 series on the harmful consequences of school choice has evoked controversy in the state’s Department of Education, and during the devastating fall flood, Smith interviewed locals navigating downtown on boats and paddleboards.

Pardue says that because Smith “can’t shake being a cop reporter,” he’ll be running toward danger until old age stops him. He’s probably right. Says Smith, “There are so many stories left to do.”

Find the Pulitzer Prize-winning series at http://www.postandcourier.com/tilldeath/partone.html.

What’s Smith been up to lately? Find out where he was during the epic flooding in October (it involves falling into a manhole) at s.uconn.edu/glennsmith. You also will find a copy of the thank you letter Smith wrote to his UConn journalism professor upon hearing of his Pulitzer win.