In rural Bihar, one of the most economically depressed regions of India, girls often drop out of secondary school by age 14 or 15 because schools tend to be far away, and the girls become involved with caring for siblings or helping out at home.

So in 2006, under a new government regime, the government of Bihar gave hundreds of bicycles – costing millions of dollars to buy and deliver – to young girls in secondary school to enable them to get to school more easily. Over three years, the program increased girls’ age-appropriate enrollment in secondary school by 32 percent and reduced the corresponding gender gap by 40 percent, according to research coauthored by Nishith Prakash, assistant professor of economics in the College of Liberal Arts and Sciences. Girls were cycling to school; the system was hailed as a huge success.

But Prakash wasn’t satisfied. He wanted to know why the program worked.

“All policies have certain goals they are supposed to achieve,” he says. “When they work, that’s only a part of it. We want to know what’s driving change.”

In theory, he expected the impact of free bicycles to be low in villages with a secondary school nearby, where girls could walk to school easily; and in villages where the school is very far away, because the cost of attending school at all would be too high. Actually testing this theory was essential, Prakash says.

His analyses determined that the program worked only if the girls lived 5 to 13 km from their schools, corroborating his theory.

“You need to understand the underlying causes if you want to replicate policies in different settings,” he says.

Prakash’s research and commentary also extends to the election of criminally accused politicians, policies to reduce crime, and even a proposed ban on alcohol across India. Through it all, he asks the same question: How do you measure policy success and identify barriers that prevent higher levels of economic development?

Electing criminally accused politicians

Despite a history of democratic and transparent elections in its 29 states, an increasing number of criminally accused politicians are being elected in India. Between 2004 and 2014, the number of Indian Parliament members who had been previously charged with a serious or financial crime increased from 24 to 34 percent.

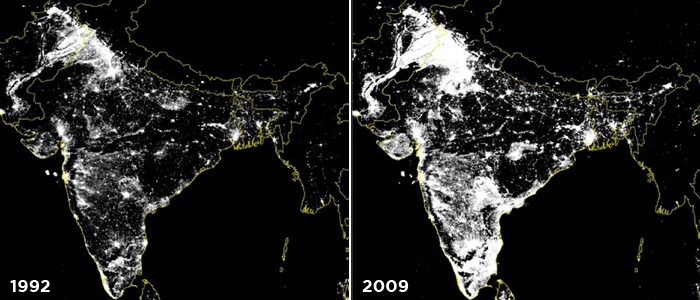

Prakash hypothesized that electing politicians accused of crimes has a negative effect on economic growth. So he and his collaborators compared the economic growth of constituencies that elect criminally accused politicians with those that elect non-accused politicians in similarly close elections. They used an illustrative metric for GDP: the intensity of lights at night, seen from space.

Results showed that, on average, election of an accused politician leads to a 22 percent lower yearly growth in the intensity of night lights. Converted to GDP, this is equivalent to a roughly 5.61-5.86 percent GDP, compared with the 6 percent GDP experienced nationally. Such a marked difference, he hopes, should help convince people that electing corrupt politicians leads to a significant negative impact on economic outcomes.

“With low levels of development, criminally accused politicians are able to cater to their caste or ethnic group, and are still able to win elections,” says Prakash. “But the aggregate outcome is negative.”

The end of ‘Jungle Raj’

Until the mid-2000s, the state of Bihar had some of the highest rates of crime, corrupt government, and manifest poverty in India. The media dubbed it “jungle raj,” meaning “law of the jungle.” The region was also infamous for frequent kidnappings.

“Criminals would kidnap doctors, engineers, and hold them for ransom,” explains Prakash.

In 2005 a new chief minister, Nitish Kumar, came into power, promising reforms that would re-establish the rule of law and reduce crime.

Since then, Bihar has experienced a renaissance: Its gross domestic product (GDP) growth, which was below the national average for decades, increased by between 10 percent and 12 percent per year between 2005 and 2012, one of the fastest growth rates among Indian states. Between 2004 and 2008, road robberies and murders also decreased markedly, and, strikingly, kidnapping decreased by 37 percent.

To understand the connection between specific policies and the turnaround, Prakash and his collaborators took on a daunting task: to collect data on all crimes committed in the state from before and after 2005. This involved individually gathering monthly information on all categories of crime registered at the state’s 853 police stations.

It was, as he puts it, “mind-blowingly difficult,” as many stations keep only paper records. With the help of the state police department, including the director-general of police, Prakash’s research assistants lugged out of storage hundreds of red bags bursting with files, and logged their information into a database. The process took almost two years.

The team’s initial data from the years 2001 to 2013 shows that two initiatives had the highest impact on reducing crime. Chief Minister Kumar emphasized the use of the rarely enforced Arms Act, which allows police to arrest anyone in possession of an illegal firearm.

“If you arrest somebody for a crime, like kidnapping, it will take time to go through the courts and several years to get the criminal convicted,” Prakash points out. “But if you arrest someone under the Arms Act, you have immediate evidence for conviction.”

The creation in 2009 of “speedy trials,” or fast-track courts, also expedited the prosecution process for serious crimes. Together, the Arms Act and speedy trials led to a sharp rise in convictions, and sent a clear, strong message to criminals.

But economic crime has risen over the same time period, which Prakash thinks is a result of the violent crime crackdown. In a new project, Prakash and collaborators at the International Growth Center in Bihar, Warwick University in the U.K., and the Paris School of Economics will examine in more detail the data behind Bihar’s renaissance, including the mechanisms of that rise.

Personal connection

Born and raised in Bihar, Prakash has mostly agreed with the Chief Minister’s new policies. But he is vehemently against a new law, which went into effect on April 1, that will ban alcohol entirely from the state. The law is meant to decrease domestic violence.

“We’re not talking about a state that has abundant resources to enforce such a ban,” he notes. “And we know, qualitatively, that these bans don’t work.”

He will watch the outcomes of the ban with interest, and possibly analyze its effects in future years.

Prakash hopes that his many projects on economics and crime in India will lead not only to better guidelines for his home country, but for developing countries around the world. If we are to know whether a political process is effective, he says, economics can provide a quantitative measure of success.