For children suffering chronic pain, taking a pill or undergoing some other medical procedure may not be sufficient, according to Jessica Guite, a pediatric psychologist at UConn Health who specializes in behavioral pain management.

Guite says it can be just as important to work with the family to address psychosocial issues, and also to encourage the child to take part in physical exercise to alleviate the pain.

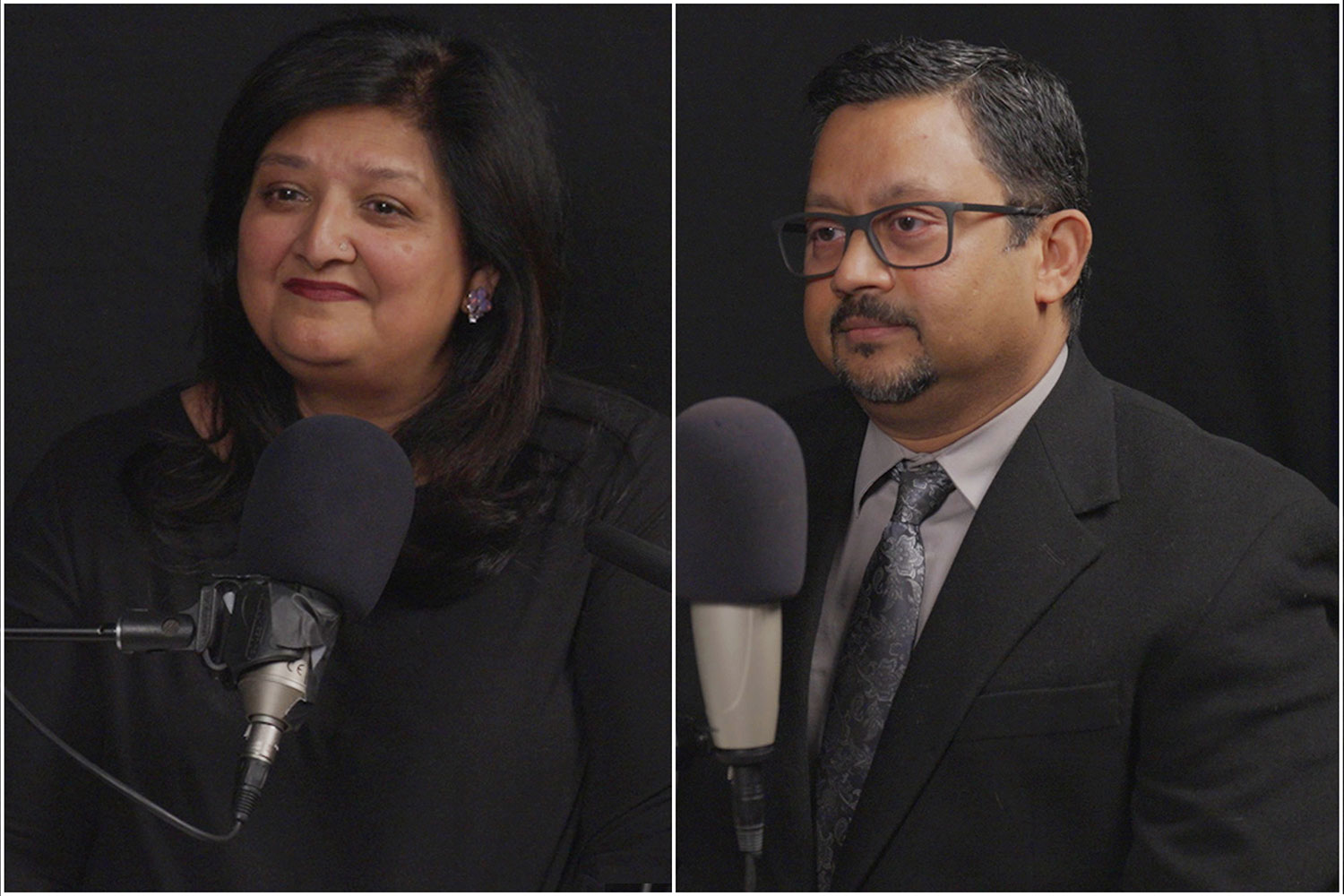

Guite is an associate professor of pediatrics at the UConn School of Medicine and member of UConn’s Center for Advancement in Managing Pain (CAMP), and is also associated with Connecticut Children’s Medical Center (CCMC). Her research focuses on improving treatment outcomes for youth with chronic pain and associated illness conditions, and their families.

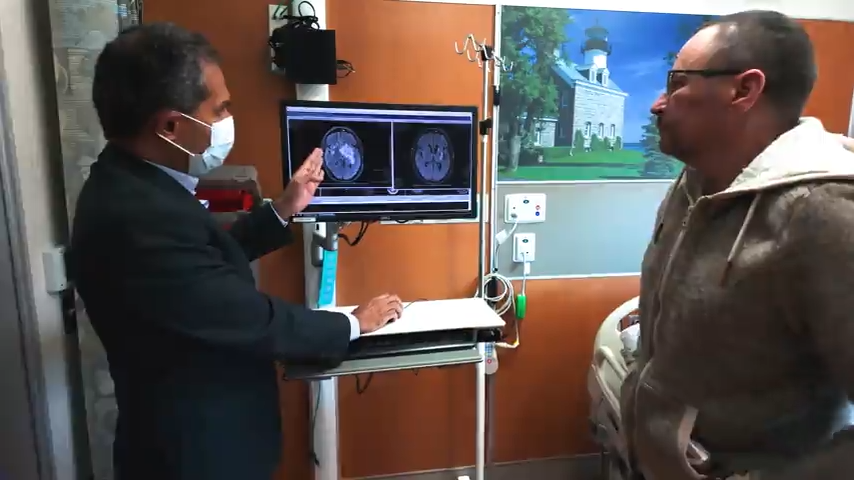

Her starting point is a child or adolescent who describes pain that won’t go away after several months or more. And the goal is to get rid of – or at least manage – that pain. She works closely with the medical team treating the child.

She says some find it surprising to think of chronic pain in children. People often associate long-term pain with middle or old age. But the numbers tell a different story. Worldwide it is estimated that pain lasting several months or longer affects 20 percent to 30 percent of children and adolescents at some time during their youth. The most commonly reported conditions are headaches and abdominal pain, musculoskeletal pain, and back pain. And it is not uncommon for these problems to co-occur.

It can seem counterintuitive to parents when we suggest activities like walking or swimming for a child who has musculoskeletal pain. — Jessica Guite

Along with the challenges associated with the physical discomfort associated with the pain, there are psychological, emotional, and social factors that often involve other family members.

“Because we’re dealing with children – and in a pediatric health care setting that can include infants, toddlers, teens, and young adults – we are also working with parents and guardians, who play a critical role in how patients respond to pain and how receptive they are to the various treatment options we have available,” Guite says.

It starts with the fact that no parent wants to see their child in discomfort. Common additional challenges include time lost from work for parents and from school for the kids; how the health of the child affects siblings; unforeseen health care expenses; and a host of other emotional and social issues.

Collectively, these challenges can add tremendous stress to the family dynamic; and understanding the multiple factors contributing to a patient’s ongoing physical problems can require patience and superior problem-solving skills on the part of a medical team.

“One of the issues we deal with on a regular basis is something we call ‘pain catastrophizing’,” says Guite, “or how disruptive pain becomes for a particular person.” She explains that every individual reacts to pain differently. In some cases, a caregiver’s concern – though well-intentioned – can make a young patient react more intensely to a painful condition than might be the case with more ‘matter-of-fact’ support.

She says research shows that chronic pain is often accompanied by increased symptoms of stress, anxiety, and depression, as well as fatigue caused by interrupted sleep, a diminished desire to participate in physical activities, and avoidance of ‘normal’ activities such as attending school and participating in extracurricular activities. That’s why it’s imperative to include management of psycho-social symptoms, as well as the physical symptoms, in any treatment plan.

But Guite says it can be a challenge to convince parents that changes in behavior, which take time out of an already busy family schedule, may be as valuable to a treatment regime as taking medication or having a medical procedure. In addition, parents’ core beliefs about a child’s pain can make it more difficult for them to pursue recommended treatments, or may lead them to engage in what she terms ‘misguided helping’ behaviors.

“It can seem counterintuitive to parents when we suggest activities like walking or swimming for a child who has musculoskeletal pain, especially when resumption of an activity after a period of inactivity can feel uncomfortable at first,” she says. “And the temptation to let a child stay home from school or an activity to ‘rest up’ when they complain of headaches or stomach aches is understandable. It’s just that some of these coping behaviors aren’t really helpful.”

From a clinical standpoint, the good news is that there are many different types of behavioral strategies a child can be taught to help alleviate the symptoms that go along with chronic pain. That’s why it’s so important to get both parents and children to ‘buy in’ to a behavioral plan, she adds, even though this sometimes requires a big leap of faith.

The kind of cognitive behavioral therapy practiced by Guite places a strong emphasis on helping youngsters and their parents to think differently about pain. Recommended strategies frequently include encouraging a child to do specific exercises, including physical therapy; get a better night’s sleep; attend school more regularly; or participate in particular extracurricular activities.

Guite works hand-in-hand with physicians and other members of a medical team, as well as with patients and their families. Her collaborative nature made joining the interdisciplinary Center for Advancement in Managing Pain a natural fit or, as she describes it, ‘a no-brainer.’

“One of the best ways to find answers to tough problems is to talk about them and listen with an open mind,” she says. “With all the expertise available through CAMP, I have no doubt we’ll find the answers to dealing with chronic pain. It may not be easy, but we’ll get there.”