UConn School of Business Professor, Colleagues Discover That Turkey’s Take-Charge Healthcare Initiative Saves Lives

Since the nation of Turkey launched an aggressive healthcare initiative, providing free and convenient access to primary care for all its citizens, at conveniently located walk-in clinics, the mortality rate has decreased, most dramatically among infants.

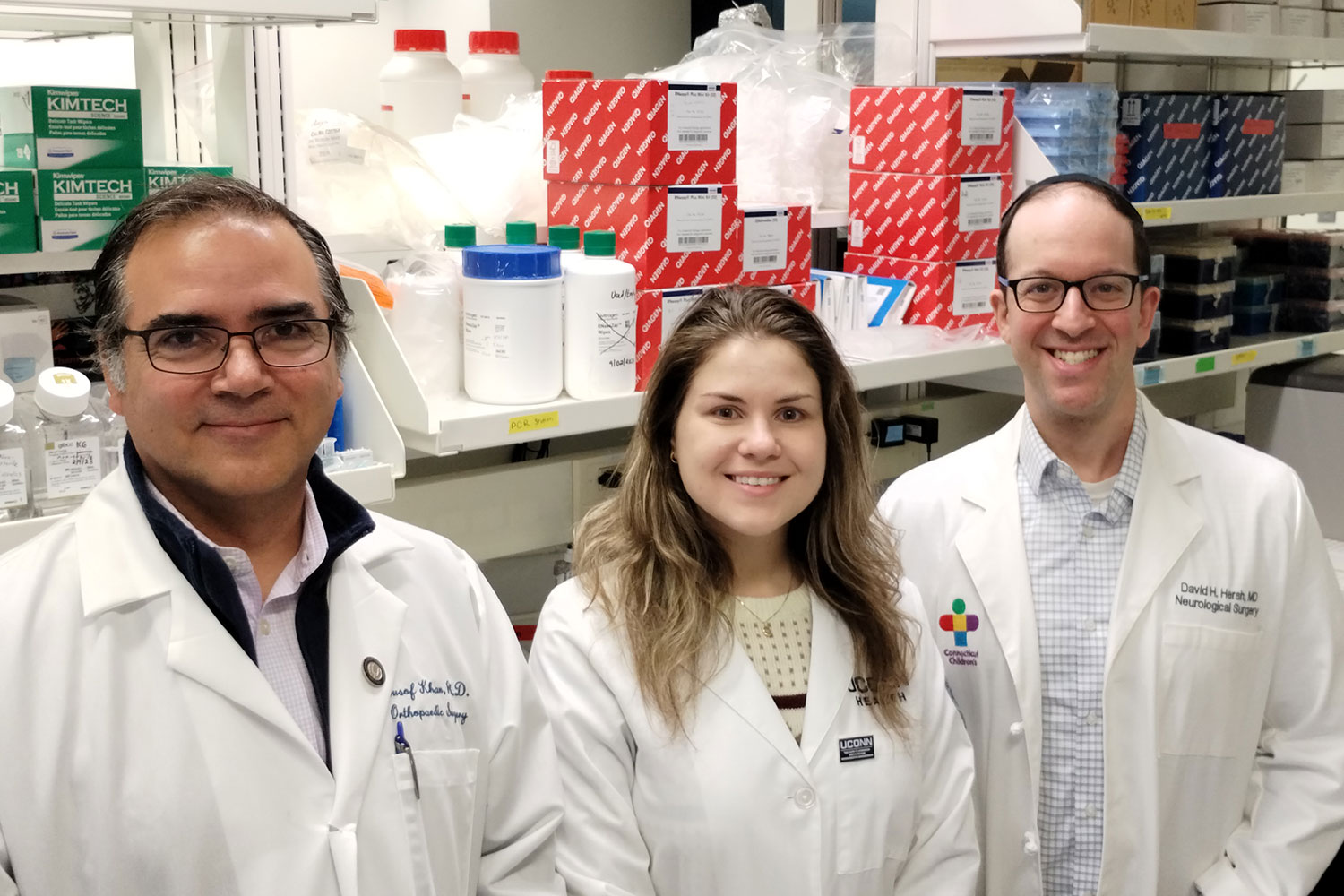

Turkey’s Family Medicine Program (FMP), which began in 2005, has had such striking and successful results that it provides compelling evidence in favor of the argument that supply-side interventions may be effective in improving public health in a developing-country setting, said Professor Resul Cesur, a member of the healthcare faculty at the School of Business and the lead author of a new study on its impact.

“This is one of the most ambitious and comprehensive efforts ever implemented in a developing country with the goal of achieving universal healthcare,” said Cesur, a health economist and native of Turkey. The work is particularly exciting because no one had previously studied or documented the impact of the program in great detail.

“Investigations of large-scale or nationwide reforms are scarce simply because such interventions are rare. The Turkish FMP presented a unique opportunity to provide insight into the impact of a nationwide supply-side intervention on population health,” he said.

The findings are of interest on many fronts, Cesur said. According to the World Health Organization (WHO) some 1.3 billion people in the world lack effective and affordable medical care. It is one of the most daunting challenges faced by governments around the globe.

Closer to home, the research may offer a fresh look at healthcare delivery to the poor population, who lack the means to travel to primary care facilities to receive basic healthcare services.

Cesur’s analysis, titled, “The Value of Socialized Medicine: The Impact of Universal Primary Healthcare Provision on Birth and Mortality Rates in Turkey,” is a National Bureau of Economic Research working paper. Cesur co-authored the paper with Pinar Mine Gunes of the University of Alberta, Erdal Tekin of American University and Aydogan Ulker of Deakin University. The researchers studied the country’s health statistics from 2001 to 2013.

Turkey’s FMP was first initiated as a pilot in 2005 in the province of Duzce, and it gradually expanded. By the end of 2010, it covered the entire Turkish population in all 81 provinces. The program provides free-of-charge primary care services to all Turkish citizens using 21,200 family physicians, who work under public contracts on a full time basis, in more than 7,000 family and community health centers.

Prior to the FMP, the delivery of healthcare had been managed through a hierarchical and fragmented system, Cesur said, which was difficult for patients to navigate. As a result, many people used hospitals for first-line treatment. Most medical care was clustered near hospitals, not in the community.

The Turkish FMP assigns every citizen to a family physician, who is the first point-of-contact for patients. Care is provided on a walk-in basis at a neighborhood clinic. Each physician has a roster of about 3,500 patients, but also has a team of nurses and midwives who assist.

The FMP provided preventive and curative medicine and rehabilitative services. Pregnant women, new mothers, infants, children and the elderly were identified as the most vulnerable patients and were targeted by the program.

The program caused large declines in mortality rates across all age groups, with more pronounced impacts among infants and the elderly. It also reduced the birth rates among teenagers, a significant task in a country that has one of the largest teen birth rates in the world.

When it came to infant health, the program reduced mortality by 14.2 percent, indicating that between 1 and 2 infants per 1,000 were saved. Among the elderly, the FMP dropped the death rate by 5.2 percent, or one life per 1,000 (or 95 per province).

The FMP is also associated with a 19.2 percent decrease in the birth rate (or an average of 38 births per province) among teenage women, which is significant in a country that has one of the highest teen birth rates in the world. In Turkey, pre-marital sex is uncommon. The physicians counseled young married women to delay pregnancy until age 20, when the risk of complications decreases.

The results suggest that the program contributed toward equalization in the mortality disparities across provinces and highlights the importance of a nationwide intervention in improving public health, Cesur said.

The study could be used as a blueprint in developing countries which face an especially steep challenge due to a shortage of trained healthcare workers, infrastructure and financial resources, Cesur said. China, Colombia, Costa Rica, Mexico, Taiwan and Vietnam are devising reforms aimed at improving health and reducing access disparities. Meanwhile, Thailand and Brazil are offering government incentives to motivate healthcare providers to expand coverage.

“The findings in this paper provide further compelling evidence in favor of the view that extending healthcare services to all citizens is critical to achieving universal coverage and improving public health,” Cesur said.