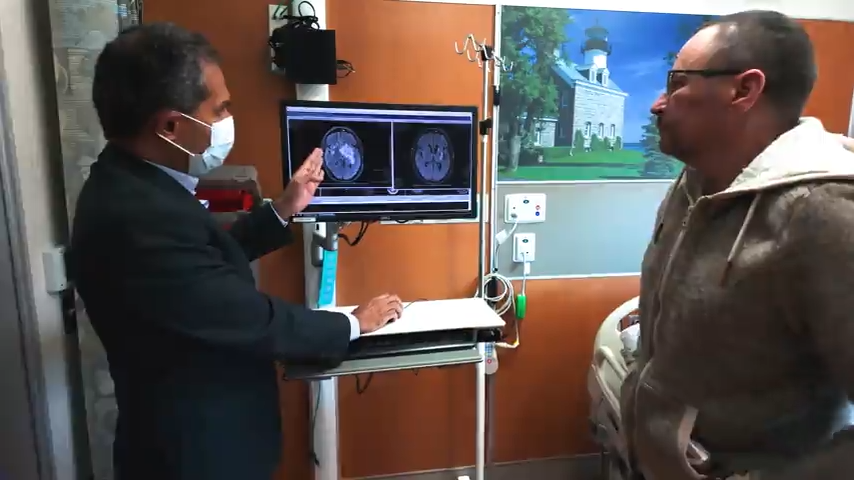

UConn’s new state-of-the-art fMRI scanner in the Brain Imaging Research Center allows researchers to visualize the brain carrying out language and other cognitive tasks in real time. The scanner, which is yielding the clearest pictures yet of the inner workings of the human brain, marks an important milestone in UConn’s continuing rise to prominence in the cognitive and brain sciences. This story is one of a series on UConn research that taps into this new capability.

When contestant Ken Jennings faced-off against an IBM computer named Watson on the TV quiz show ‘Jeopardy’ in 2011, the riff was the epic confrontation between man and machine. The idea was that one would be a winner, the other a loser. It was all in good fun, and Jennings (the ‘loser’) is now doing commercials for IBM touting Watson’s ‘super human’ capabilities.

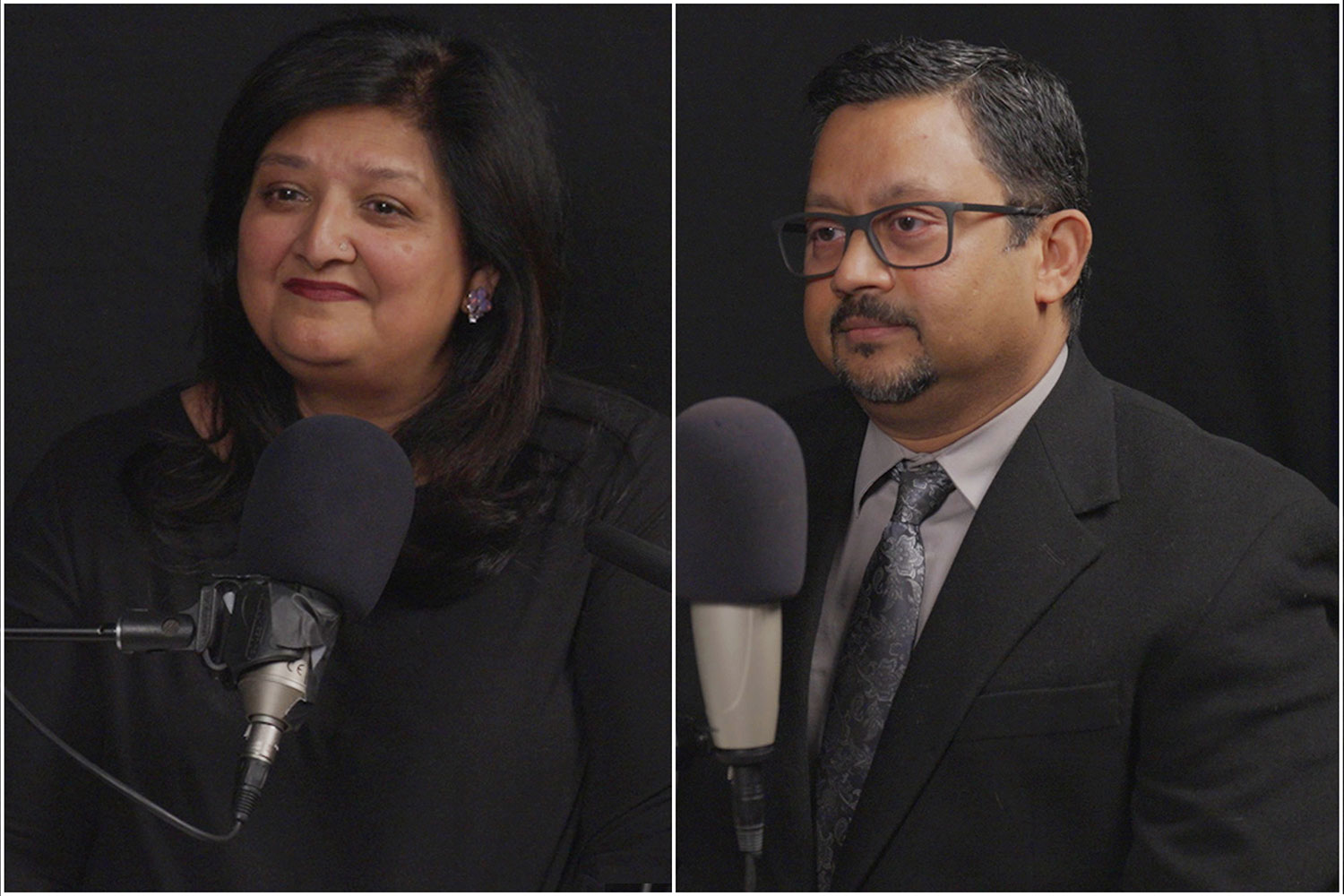

When it comes to the use of sophisticated brain-imaging technology in the study of emotion, communications professor Ross Buck says there is no ‘man versus machine’ conflict. For him, UConn’s highly sophisticated new functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) machine makes it possible to study what’s going on deep within the brain in real time, and that is helping to inform his decades of research on non-verbal communication.

“This is an exciting time to be studying the brain and cognitive science,” he says,” because we can finally get a look at what is actually happening. The fMRI makes it possible to observe aspects of behavior that were inaccessible before; I see a lot of commonalities in what’s being found by the new technology and what we have understood from earlier animal research. This is both affirming and challenging, because now we have the means to explore emotion on so many different levels. It feels like the sky’s the limit.”

We now have the opportunity to actually see how the brain is reacting to emotional stimuli, and things that were previously hidden are now observable and measurable.–Ross Buck

Buck’s academic focus on non-verbal communication began back in his days as a Ph.D. student at the University of Pittsburgh. That was in the late 1960s, and it came on the heels of some ground-breaking research by Harry Harlow, a professor at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. One of the conclusions coming out of Harlow’s experiments on rhesus monkeys was that social isolation inhibited social and cognitive development. This included failure to develop the ability to read the facial expressions of other monkeys – something that individuals who had been raised normally could do easily.

Buck was brought into a lab at Pittsburgh as a social psychologist, to see how well humans could read other people’s expressions. “We would show people various types of emotionally loaded slides – things that were scenic, pleasant, sexual, scary – a whole range of images designed to elicit an emotional response,” he recalls. “We told them we were interested in their physiological responses and their subjective reports of what they had seen.

“What we didn’t reveal to them until later,” he adds, “was that we were also filming them with a hidden camera. Then we were asking other individuals to interpret what the primary viewers were seeing.”

He says that, on average, most people could tell what types of slides women were watching better than they could tell what the male viewers were watching. Also, those who were good ‘senders’ of emotion, and who were very expressive, tended to have smaller physiological reactions to the slides, including fewer skin conductance deflections – a measurement of how the skin transmits electrical activity – and less heart rate acceleration.

These findings may at first seem counter-intuitive, but what they suggested to Buck was that people were either internalizing or externalizing their emotional responses, and also that there were distinct differences between the sexes.

This opened a flood gate of questions concerning the nature of emotionality and whether the expression of emotion is primarily a function of nature or nurture. The chance to pursue this avenue of study led him to UConn in the mid-1970s, where he has held joint appointments in the departments of communication and psychology ever since.

Among the things the fMRI allows Buck to do is see what’s actually happening in the evolutionarily primitive area of the brain known as the limbic system, which controls emotions, and in the amygdala, which plays a role in the processing of emotions, the stress response, and aggressive behavior. The fMRI ‘lights up’ when people are experiencing emotional empathy – detecting the feelings of another person – and cognitive empathy, which measures intentionality and reading what another person is thinking. All of this adds to the body of knowledge that helps in the understanding of human behavior.

“Being in this field is a little like being a kid in a candy shop,” Buck says, “because we now have the opportunity to actually see how the brain is reacting to emotional stimuli, and things that were previously hidden are now observable and measurable. As we become more emotionally educated, we’ll have a lot better idea of why people behave the way they do.”