Adult stem cells may be the key to targeted regeneration of body tissues, researchers said at the StemConn 2015 conference held April 27 in Hartford, Conn.

“Adult stem cells know what to do. You just have to get them into the right place,” said Frank McKeon, chief scientist at Multiclonal Therapeutics, a startup hosted in UConn’s Technology Incubation Program.

Many people are familiar with the term stem cell, which refers to cells that haven’t yet turned into a specific cell type or tissue. When stem cells are taken from embryos, they have the potential to turn into any possible type of cell. Adult stem cells, however, are firmly committed to the general organ or tissue they come from. An adult stem cell from the duodenum (the upper part of the small intestine) can turn into any of the different cell types in the duodenum. But it will never turn into a cell found only in the lungs, for example, or even a cell for the large intestine.

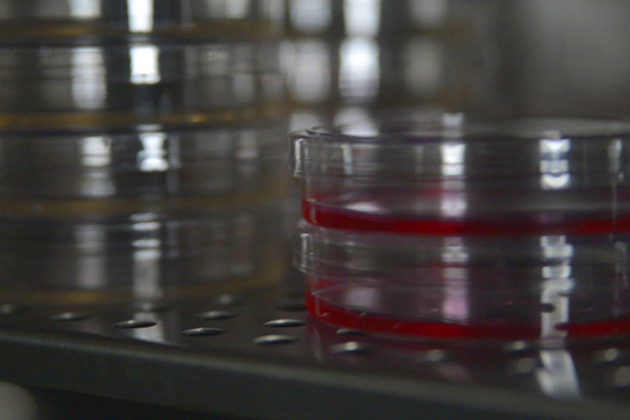

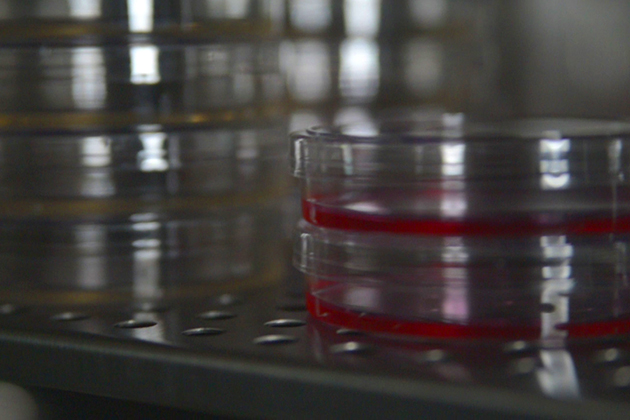

When adult stem cells are cloned, they can spawn an army of cells that reconstruct a specific tissue almost indistinguishable from the tissue they came from. This means that if you can get the right adult stem cell, you should be able to repair almost any part of the body. Just clone the adult stem cell, and then deliver those clones to the site of the injury.

Multiclonal Therapeutics has been working with adult stem cells to repair lung tissue damaged by chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. The work may also be applicable to people with lungs damaged by severe bouts of the flu or pneumonia.

McKeon also cited work by Wa Xian, another Multiclonal Therapeutics researcher formerly jointly appointed to UConn and the Jackson Laboratories. Xian found that adult stem cells removed from advanced ovarian cancers will faithfully regrow the same cancer in the lab. Xian has used these cancerous adult stem cells to test for drug resistance and susceptibility. Such a strategy could be one way to find personalized treatments for cancers.

As the ovarian cancer example shows, adult stem cells don’t always behave well in the body. They can cause disease when they form the wrong type of cell in the wrong place. In Heterotropic Ossification (HO), for example, adult stem cells go horribly wrong and create bone and cartilage where there should be muscle. War veterans with blast wounds and amputated limbs sometimes develop HO near the site of the amputation. Other people are born with the condition, and every little bruise or minor injury can cause extra bone growth and gradually fuse their bones and joints together.

HO appears to be caused by Tie2+ cells, a special type of adult stem cell, reported Arpita Biswas during an invited talk at the conference. Biswas, a UConn graduate student in molecular and cell biology working in David Goldhamer’s lab, gave the talk after receiving the Milton B. Wallack Trainee Award for Excellence in Stem Cell & Regenerative Medicine Research.

The Tie2+ cells that cause HO are able to turn into either bone, cartilage, or fat. Their native purpose is unknown, and Biswas and her colleagues found them in other parts of the body besides muscle tissue. Biswas’s next step will be to look at whether the Tie2+ cells play a role in certain forms of muscular dystrophy, in which muscle tissue is replaced by fat. The team is also working on small molecule inhibitors that might stop the cells from forming the strange, bony deposits that characterize HO disease.