James Bernot ’12 (CLAS), MS ’15 can pinpoint the exact moment he realized that he was a scientist.

The UConn biological sciences major had spent two of his college years studying parasites in the laboratory of Janine Caira, Board of Trustees Distinguished Professor of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology and one of the world’s foremost tapeworm biologists.

Now, as a graduating senior, he stood in front of a room of scientists at the annual meeting of the American Society of Parasitologists in Anchorage, Alaska, and explained to the crowd his research discovering new species of tapeworms and their parasitic existence within the guts of smooth-hound sharks.

He describes the experience in one word: empowering.

“I suddenly realized that I knew this system better than anyone else in the room,” he says. “I thought, I’m a world expert on this small subject, and I’m sharing new knowledge with people. And that makes me a scientist.”

Bernot is just one among hundreds of students who have passed through Caira’s laboratory in the past 30 years. Many show up for the sharks, Caira says – “we get a lot of shark groupies,” she jokes – but even when they realize the lab is all about parasites, they stay for the experience of discovery. They stay to become scientists.

Necessary Knowledge

At the heart of training young scientists, says Caira, is the idea of fundamental research. Her laboratory focuses on the taxonomy, or the family trees, of tapeworms. Of the some 7,000 identified tapeworm species, about 1,000 live and evolve in the guts of sharks and rays, making them an ideal system to study the coevolution of parasites and their hosts.

In the past five years alone, Caira and her students journeyed to the shores of Chile, Ecuador, Senegal, South Africa, Portugal, India, and Vietnam, where they collected sharks, often bycatch from local fishermen’s boats. The researchers dissect the fish, pull out their tapeworms, and bring the parasites back to Caira’s UConn laboratory.

There they wait, preserved in jars, for a student like Bernot, or Carrie Fyler ’09 Ph.D., to identify them.

“When you’re in the field, you’re out on a beach in the sun working for 10 hours each day – there’s a very raw element to it,” says Fyler. “And then when you get back to the lab, you have your microscope and your slides, and you spend hours just drawing, looking, analyzing, and learning.”

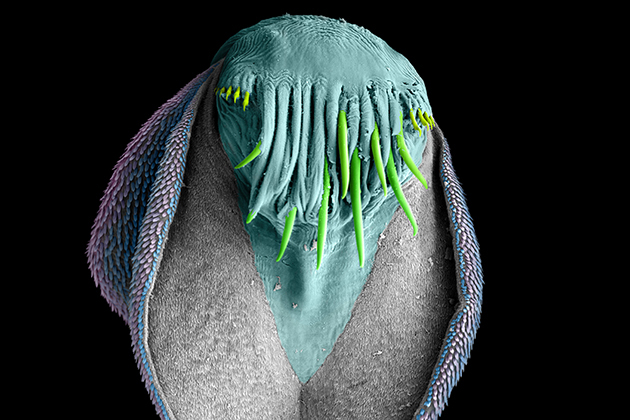

Students identify the tapeworms based on their characteristics, like their head-like scolex; their hook-like rostellum that attaches to their host’s digestive tract; and their sections of proglottids, which they use to reproduce.

Caira says that in her lab’s collections, there are probably 200 undescribed species of tapeworms, ready to be discovered.

“They’re glorious,” Caira says. “Their morphology is spectacular. And they’re better taxonomists than we are. The tapeworms always tell us the truth.”

Learning about the habitat of a study organism in the field, and also spending time studying them in-depth in the laboratory, is the best way to develop a burgeoning scientist, Caira says.

“We do fundamental research to learn about the world,” she says. “The world wouldn’t survive without parasites. So if we stopped basic research, we wouldn’t go anywhere else, and we would stop learning about what makes us all exist.”

The Tapeworm Teacher

One of the biggest thrills of Fyler’s graduate work was naming a new species of tapeworm – one of 15 new species she discovered during her graduate work – after Carl Zimmer, author of the book Parasite Rex, which first inspired her to study parasites.

“People like to study charismatic megafauna, like whales,” she says. “But parasites and their hosts are a major reason all of biodiversity came to be. I liked the idea that tapeworms are the underdogs, and comparatively little is known about them.”

Now, Fyler’s students at Montclair Kimberley Academy in Montclair, N.J., where she teaches biology, are budding tapeworm experts. Fyler spends three weeks at the end of each year teaching students about parasite origins and diversity.

“I’m constantly using my research as an example,” she says. “The students love it. And the skills I gained at UConn, I use every day, whether in the classroom or in the laboratory.”

Biological Backing

Although Caira’s research is funded by grants from the National Science Foundation, her work training students has been exponentially expanded over the years by private support.

A chance encounter between Caira and parasite devotee Judith Shaw ’48, who worked on a national parasite catalog at the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Agricultural Research Center in Beltsville, Md., led to Shaw establishing UConn’s Judith Humphrey Shaw Parasitology Fund in 1991.

“Judy’s generosity has had a phenomenal impact on parasitology and the training of students at UConn,” says Caira. “She’s made it possible for students to travel nationally and internationally and experience science in the wild, something you just can’t replicate here on campus.”

More than 200 students and dozens of international researchers have benefited from the fund, Caira says. Its major role has been to enable students to travel to national and international conferences; among other trips, Fyler traveled to Slovakia to attend a workshop.

Says Bernot, “I wouldn’t be where I am without that support. The meeting in Anchorage was the experience that changed my future.”

Bernot is currently finishing his master’s degree at UConn and applying for Ph.D. programs in parasitology. He hopes to study how parasites evolved in the first place – another basic research question about which, he says, scientists know comparatively little.

And when Fyler mentors her biology students and sends them off to college, she hopes they take with them an appreciation for the unsung heroes of the natural world.

“You go and study your whales,” she jokes. “I’ll always be a tapeworm lover.”

The Department of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology is celebrating its 30th anniversary this semester with a series of special lectures and events. Learn more.