One class at the University of Connecticut tries to upend a lot of what students learned while growing up.

Students in Women’s Studies class WGSS 3271, a one-credit course offered in the fall, discuss prevalent societal messages about sexual assault or rape in which the burden is often placed on the victim, and they learn how to unravel the culture of violence.

“Don’t walk alone at night, don’t accept drinks from strangers or leave your drink unattended, carry mace or pepper spray, take a self-defense class. The common thread is that the onus is on the potential target,” says Lauren Donais ’08 (CLAS), coordinator of the Violence Against Women Prevention Program and one of the instructors for the class. “Instead, we advocate that the onus of preventing rape should be on potential perpetrators.”

The class covers issues surrounding sexual assault and intimate partner violence, gender norms and expectations, the dynamics between men and women, healthy and unhealthy relationships, and images in the media.

The students also develop facilitation skills and learn how to educate their peers on these issues. On completing the course, they are able to facilitate six interactive workshops that explore the continuum of sexual violence.

“Let’s talk about why people are likely to assault others to begin with and how we can get to a place where that’s no longer the case,” says Donais. “That requires a cultural shift, and that cultural shift begins with these students. That’s why the peer education model is so valuable – peer educators have more credibility.”

Many who have taken the course in the fall and wish to continue with VAWPP also enroll in the one-credit WGSS 3272, offered each spring. The second semester class is an opportunity for students to organize many of the Women’s Center’s events, including the annual Take Back the Night vigil, and design and facilitate their own group workshop, where they can ask questions, voice concerns, and share experiences.

As peer educators, they also offer workshops by invitation in residence halls and in classes, and facilitate mandatory sessions for incoming freshmen during summer orientation.

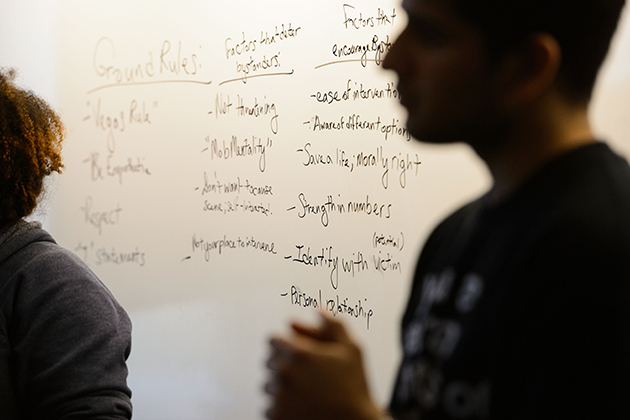

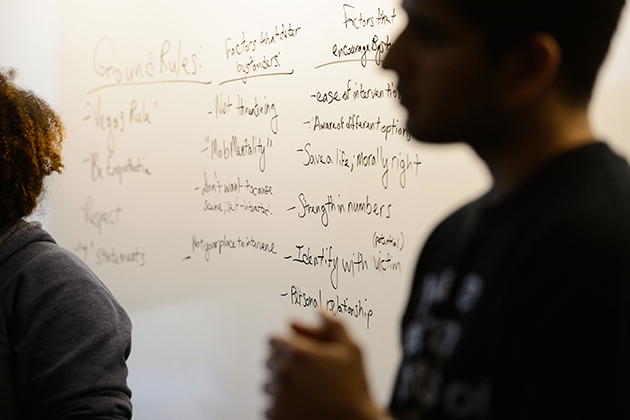

During a recent invited workshop, two peer educators – one a junior, the other a sophomore – skillfully guide a discussion on bystander intervention strategies, helping students in the class figure out strategies to quickly assess a violent situation and decide whether and how to act safely. They suggest a range of effective alternatives to consider, besides directly intervening.

Some students note that they have been witnesses to violence, faced with a difficult choice of whether to try to help; some have been a victim and had wished someone would intervene.

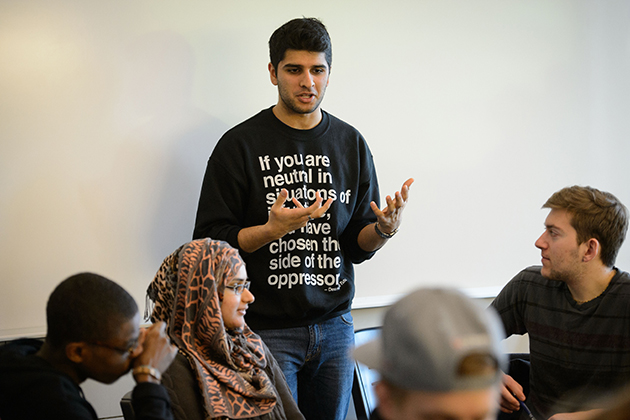

“The goal is to make [the response] become instinct,” says peer educator Varun Khattar ’16 (CLAS). “It’s never going to be easy, but if you think about it ahead of time, it will be easier to decide what you can do to intervene.”

At the end of the workshop, co-facilitator Stephanie Lumbra ’15 (CLAS) tells the students, “Go back to your dorm … and talk about what we’ve talked about today. The more we talk about it, the more likely that you can be a positive bystander in the future. And if you’ve been a victim of violence and someone intervened on your behalf, thank them.”

Khattar was inspired to become a peer educator by a workshop on consent during orientation. “I felt my undergraduate education would not be complete without participating in social justice and student activism,” he says.

A marathon, not a sprint

The work is not for the faint-hearted.

Not everyone who is exposed to the peer educators’ message is receptive. “Certain students don’t want to engage with the conversation around sexual violence,” says peer educator Brittany Carrier ’15 (CLAS). “There are some audiences that are receptive, but there are a lot more resistant groups.

“This work is hard and draining,” she continues, “but I don’t think I could ever walk away from it because of the moments of realization and change I sometimes see in the students’ eyes, and also because of how I still learn from my facilitations and unpack toxic beliefs in myself.”

Adds Carrier, “While it hurts to hear, ‘She shouldn’t have been drunk if she didn’t want to be raped,’ it’s important to have that said in order for us to properly unpack the sexism in it, along with how men feel entitled to women’s bodies, the fact that it perpetrates the idea that men can’t control themselves, and more. … Just because a group is resistant doesn’t mean that there wasn’t any meaningful change or critical thinking done.”

The effectiveness of a prevention program is, by its very nature, hard to measure. The peer educators have learned to see their work as an ongoing process.

“It can be easy to feel discouraged and overwhelmed by the immensity of this issue and our limitations as humans and activists,” says Khattar. “I constantly have to remind myself that the movement to end sexual violence is a marathon, not a sprint.”