UConn’s George Safford Torrey Herbarium, with 200,000 specimens of plants, is a leading source of information for botanists throughout the world.

Its state-of-the art facility contains herbaceous and woody plants collected over the past 100-plus years both locally and from around the world. And now that its records have been digitized thanks to a National Science Foundation grant, the herbarium can be accessed by researchers, teachers, and students anywhere in the world, who can explore the collection online.

The global scope of the 21st-century herbarium in Storrs would have been unimaginable to those who started the collection back in 1898, when the first specimen, a cinquefoil, was officially accessioned.

That cinquefoil (Potentilla canadensis) came from the collection of H.A. Ballou. An entomologist by training, Ballou was hired by the Storrs Agricultural College (precursor to the University of Connecticut) to teach freshman classes in the Department of Botany and Military Science. He was the first on campus to treat the study of botany as an important part of the curriculum of the day, considering it just as worthy as the more favorably considered studies in horticulture, for which the college was known.

In botanical parlance, the collection became known by the acronym ‘CONN,’ and it is at once an active site for current academic pursuits and a valuable lesson in the history of the University.

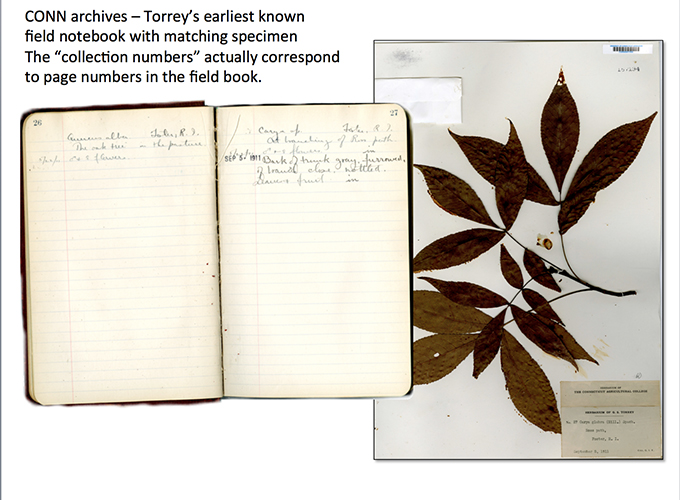

It is named after George Safford Torrey, a botanist who oversaw the collection from 1915 to 1956 and for whom the Torrey Life Sciences Building is also named. Torrey became head of the Department of Botany in 1929 and served in that role until 1953. During his tenure, the herbarium made significant strides in the number, variety, and quality of its samples.

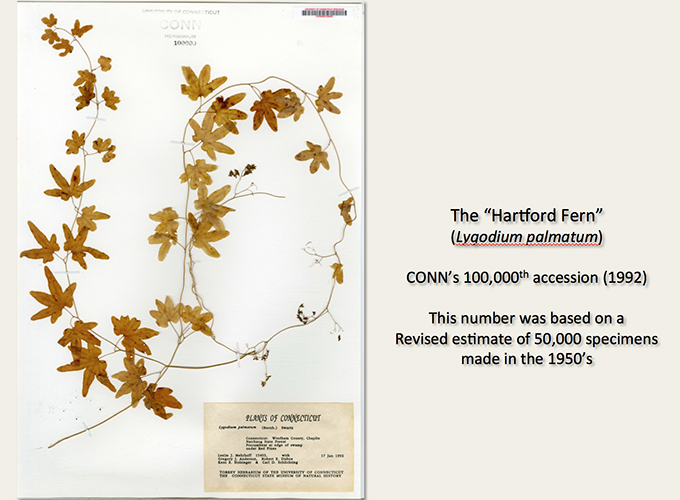

Donald Les, current director of the herbarium and professor of ecology and evolutionary biology, says that UConn’s collection has grown from 100,000 items in 1992 to more than 200,000 over the past two decades.

“Our collection is intermediate in size [compared to other herbariums], with about 200,000 items,” Les says. “What sets us apart, thanks to a nearly $500,000 grant from the National Science Foundation, is that over 165,000 of our specimens have already been captured with digital imaging and are available on our database. This means that anyone, anywhere in the world, can go online and access the information.”

He explains that although herbariums such as UConn’s are used to lending items to researchers, similar to the inter-library loan service for books, it is safer for the specimens and much more efficient for scholars to be able to view high-resolution images that have been digitally scanned or photographed. Every item is geo-referenced and accompanied by detailed information, including date and time of collection, soil conditions, the name of the person who collected the specimen, and more.

“When you click on an image,” Les says, “the result is amazing. The magnification is about 25x – which is what you get using a dissecting microscope. Everything is high resolution and gives a beautiful three-dimensional image.”

In addition, the herbarium’s website uses the Berkeley Mapper program to plot geo-referenced specimen data in conjunction with Google Maps. This feature allows a researcher to go to the website, select a particular plant or taxon, and then locate specimens using the mapping program.

Les says the website is also an important source of information for Connecticut’s primary and secondary school teachers. “We provide lesson plans about how climate change affects plant habitat, invasive species identification, how to make a plant collection, and other things that are designed to get students really engaged,” he says.

The NSF grant received in 2009 provided the funds for the project, but it was UConn staff and students who put in endless hours photographing and scanning specimens and deciphering hand written notes dating back over a hundred years. Included were the records of Ballou, Torrey, famed geneticist and plant scientist Albert Francis Blakeslee, who taught in Storrs from 1907 to 1915, and the late Les Mehrhoff, plant collections manager from 1996 to 2001 and longtime research associate and educator, who donated more than 20,000 of his own specimens to the herbarium.

During the past four years, Robert Capers, current manager of plant collections, led a group of more than 50 students, who worked hard to get the collection into its present format. While the actual specimens are carefully preserved in climate-controlled files in the library at the Biology/Physics Building, the entire collection can now be instantly shared online with scientists, teachers, and students throughout the world.

For photos of some of the specimens, see the UConn Today Flickr gallery.