The international human rights scholar who developed the core principles endorsed by the United Nations for international corporations to protect human rights in the conduct of their business says much more work will be needed to implement those guidelines.

Addressing an audience of students, international experts in human rights, and government officials, John G. Ruggie of the Kennedy School of Government at Harvard reflected upon his six-year effort to develop what are known as the “Ruggie Principles” while delivering the Raymond and Beverly Sackler Distinguished Lecture at the Thomas J. Dodd Research Center on Thursday.

“I think the results we have today are positive,” Ruggie said. “When I presented the Guiding Principles to the U.N. Human Rights Council, I said I am under no illusion even with this endorsement that this will solve all human rights and business challenges. It’s not going to bring them to an end. But it is the end of the beginning. For the first time, we now have a common foundation on which to build. We have a common understanding what the minimum standards ought to be for states and for governments. There is much more to be done. I am the first to insist that much more should be done.”

Ruggie delivered his remarks before an audience that also included representatives of global business, government officials, and scholars who will meet today at the Dodd Research Center in a roundtable discussion on how to implement the “Guiding Principles for Business and Human Rights” adopted by the U.N.

A wide range of actors

In tracing the history of his work developing the principles while serving as the U.N. Secretary-General’s Special Representative for Business and Human Rights, Ruggie said he faced a formidable task in trying to affect the conduct of 193 sovereign states, 80,000 multinational corporations with 800,000 subsidiaries, and millions of their suppliers.

“Herding cats is an insufficient metaphor,” he said, drawing laughter. “It doesn’t begin to describe the challenge of this situation.”

He said the key to formulating guidelines that could be acceptable to such a wide range of actors on a global stage was to involve as many of them as possible in a process that included 47 international consultations, with groups ranging from indigenous people in South America and sweat shop workers in Asia, to Russian businessmen and numerous governments around the world, all in an attempt to generate a consensus behind a set of core ideas for governments and businesses to promote, protect, and advance the course of human rights.

While many global issues are resolved using treaties among nations, Ruggie said those negotiated agreements can take years. He cited the “Declaration of Rights of Indigenous Peoples” adopted by the U. N. General Assembly in 2007, which took 26 years to complete.

Ruggie said he wanted to find what he described as “a more heterodox solution,” one that involved all of the interested parties who would be affected by the Guiding Principles.

“It’s not a problem that is going to be solved by governments alone, business alone, or civil society actors alone,” he said. “All of them have important contributions to make to an overall solution. They need to be drawn together. Left to themselves, they’re going off in different directions … we spent as much time promoting the Guiding Principles as developing them.”

Core components

Ultimately, Ruggie’s work resulted in the three core components of the guidelines: The state’s duty to protect against human rights abuses by third parties, including business; corporate responsibility to respect human rights; and greater access by victims to effective remedy, both judicial and non-judicial.

He said there are three specific areas to address to implement the guidelines on a global scale:

Capacity building. Supporting small and medium-sized enterprises, supporting particularly small developing countries, to help build the capacity to act on the things we agree should be done. “We underestimate how important lack of capacity is for both countries and business to do the right thing,” he said.

Corporate law and securities regulation. Establishing the concept of “corporate culture.” Ruggie cited Australian criminal law, under which a company can be held liable if its corporate culture was to direct, encourage, or tolerate wrongdoing by an employee, but only the employee could be tried if there was a set of systems in place that clearly discouraged this behavior.

International law should recognize corporate liability. “The international community itself through an intergovernmental process needs to establish once and for all that not only natural persons can commit crimes against humanity, but legal persons can also,” he said. “We no longer accept the idea that sovereignty can be used as a shield behind which governments can commit abuses against people. Surely the corporate form should not be a shield either for allegations or for abuses of conduct that may amount to internationally recognized crimes.”

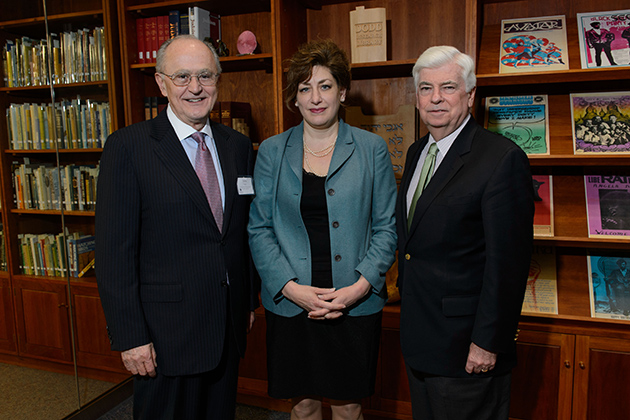

Former U.S. Sen. Christopher J. Dodd introduced Ruggie before the lecture. The Thomas J. Dodd Research Center is named for his father, a U.S. Senator and Member of the House of Representatives who served as a prosecutor during the Nuremberg Trials after World War II. During a news conference earlier in the day Dodd, now chairman and CEO of the Motion Picture Association of America Inc., spoke about his father’s legacy living on at the University.

“My father’s been gone many, many years but his epiphany as a public person and as a human being occurred during an 18-month period in a destroyed city in Nuremberg,” he said. “His life was never the same thereafter. Everything he did after that in many ways was seen through the prism of the Nuremberg experience. While he was long gone when this Center was established, I like to think he’d be very much supportive of the idea we’re gathering today to talk about, this subject matter is something I think he would have endorsed wholeheartedly. I’m pleased there’s a place that exists that bears his name, committed to an issue that almost 70 years ago he became an evangelist for – that is, the human rights of people.”