In the world of high-tech warfare, where computers and Predator drones are on the front lines, what are the ethics of deciding who is targeted and killed?

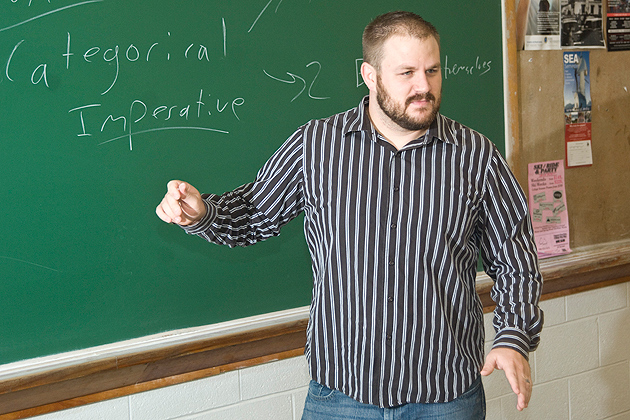

While few people are working in this field of ethics, its problems have zeroed in on Bradley J. Strawser, a Ph.D. candidate in philosophy who will graduate in May.

“These are huge ethical questions,” he says.

Strawser is a classical ethicist, but his applied work on the ethics of modern warfare has made him sought-after by the military and policy institutes, as they scramble to come to terms with new combat technologies.

He is already finishing a fellowship at a think tank in Maryland that specializes in military ethics, and he has two positions lined up after he completes his doctorate.

“Warfare is really changing in a variety of ways,” says Strawser, a veteran of eight years of active duty in the Air Force, where he was an anti-terrorism officer for a time and also taught philosophy at the Air Force Academy.

He is now a resident research fellow at the Stockdale Center for Ethical Leadership associated with the Naval Academy in Annapolis, Md., where he studies the ethics of cyber warfare. After he earns his Ph.D., he will head to Monterey, Calif., where he has a tenure-track appointment at the Naval Postgraduate School. But for part of each year, he’ll head to Oxford, England for a three-year postdoctoral appointment.

Strawser has written several papers on the ethics of using drones, or unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs), and he is editing a forthcoming Oxford collection of essays on the topic.

“Drones are really tricky,” he says.

On the one hand, he says, they should be used if you can protect a pilot or soldier from injury and your cause is just.

Arriving at that conclusion surprised him. “I went into this whole thing being ethically suspicious of drones,” he says.

But the real-world implementation of unmanned drones delivering bombs tends not to be ethical, he says. For example, their use by the CIA, a nonmilitary organization, to kill people who are targeted as suspected threats needs to be questioned. Violating national sovereignty and the victims’ due process are among his concerns.

Justified uses would be if Poland had been able to use drones in World War II when it was invaded by Germany, or, more recently, if they had been available to Kuwait in 1991, when it was invaded by Iraq.

How moral responsibility shifts for soldiers when they use new technologically sophisticated weapons also needs examining, Strawser says. If a computer can calculate a targeting decision much faster than a human, is the decision ethical? Most drone pilots are based in Nevada, controlling UAVs that are hovering to strike half a world away. The pilots are in combat virtually, and may then go home to a PTA meeting or a soccer match – a “weird cognitive dissonance” unlike the situation faced by soldiers in the field, says Strawser.

On the other hand, you could argue that they are under more oversight than a combat soldier, since their work is monitored. Drones can identify targets more accurately and can lower collateral damage. They also can be used in humanitarian ways, such as in the Libya intervention.

“I don’t think there is any knock-down principle of why they’re wrong,” he says.

The specter that scares him is autonomous drones – those that operate without pilots on the ground. If artificial intelligence improves enough, it would be possible for a hovering drone to lock in on a target without human support.

“Some people think that would be an improvement,” says Strawser, because computers are not emotionally involved in a decision to strike.

He disagrees: “You need to have a human agent involved who’s morally responsible.”

One thing is certain: “The technology is going faster than the ethics and lawmakers,” he says.

That prospect will provide job security for this philosopher for some time, as he works on the ethical and moral issues that policymakers will face.

“It’s an exciting field to be part of right now,” he says.