The acclaimed actress and humanitarian activist discusses her efforts to document the cultural traditions and oral history of refugees from Sudan and Darfur and the research archive she has established at the Thomas J. Dodd Research Center. She delivered remarks to graduates of the School of Fine Arts during Commencement Ceremonies in 2011.

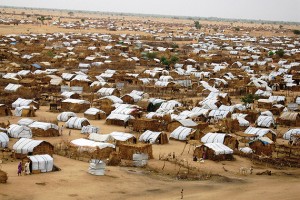

I first visited Darfur in 2004, during the peak of the slaughter of the civilian population and the rampant destruction of their homes, the year after Sudanese president Omar al-Bashir and his cabal launched a merciless campaign of destruction upon the non-Arab peoples in Darfur. Nearly 3 million survivors fled to hastily made camps scattered across Darfur and eastern Chad.

Today, 80 percent to 90 percent of Darfur’s villages are ashes or are occupied by others. The Darfuri people have lost everything. Now, too, their very culture and traditions are at risk. I pledged to help them preserve their heritage and their cultural traditions.

I’ve been to Chad and Darfur 15 times to meet and advocate for Darfuri refugees. I’ve been working to help document the rich cultural traditions and oral history of those Darfuri peoples targeted for extermination by the government of Sudan, primarily the Fur, Zaghawa, and Masaalit. In April 2009, I spent a month in the Oure Cassoni refugee camp. I told the refugees that I would be at a designated spot at the edge of the camp every day for a month. I would simply operate the camera. They would decide what stories and traditions they wanted to share with me. The Unda – the community leader – explained to me, “You know us very well. You know we are mourning. We are suffering. We do not do these celebrations in the camps.”

I made it clear that I understood that they are suffering and that this project was borne of my deepest respect for them. The archives must exist for the children who are growing up in deplorable camps and amidst violence. The archives are for them, and the children who otherwise would never know their own heritage.

During that month I was at the camp with my camera, there were thousands who came each day. I have filmed some 35 hours of singing, dancing, celebrations of coming of age, marriage, planting, harvesting, visiting neighboring villages, children’s stories, mourning, and honoring the dead. The elders shared their memories and the stories told to them by their grandparents. The stories went back 300 years. The refugees took over this project as their own, which, of course, it is.

At the end of my stay, the refugees donated some 200 artifacts they had brought with them when they fled their villages, everyday items they had used before their lives were destroyed. The artifacts were photographed and are currently being stored at the U.S. Embassy in Chad.

The project has in so many ways exceeded my goals. I could not have anticipated such whole-hearted support from the refugees. But at least one more trip back will be necessary to visit other camps in another part of eastern Chad in order to film the people of north Darfur, where the traditions are different.

The primary importance of the archive is that it will exist for Darfuris in the future, but also that it will exist as a tool to educate others about the rich and meaningful customs and traditional way of life that once was. I believe that seeing the ceremonies and hearing these stories will bring Darfur’s remarkable and courageous people into focus in new ways.