This story is the fifth of a multi-part series on the history of the Health Center. The entire series can be read at the Health Center’s 50th Anniversary website.

This story is the fifth of a multi-part series on the history of the Health Center. The entire series can be read at the Health Center’s 50th Anniversary website.

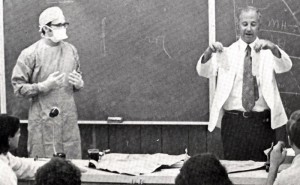

Educating and developing future physicians and dentists is complex. UConn’s Schools of Medicine and Dental Medicine began with a curriculum that was among the best of its time, and that has continued to evolve as teaching concepts and medicine itself have changed.

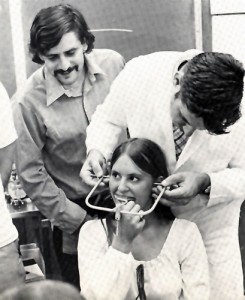

One of the distinctive features of the curricula, then and now, is that medical and dental students follow almost identical courses of study during their first two years. Dr. Monty MacNeil, current dean of the School of Dental Medicine, says this is both rare and desirable. It was – and is – unusual to have medical and dental schools so integrated with each other. Even today, some university medical and dental schools may share a campus, but are philosophically and practically very separate entities, whereas at UConn, MacNeil says, “We are fully integrated into the academic Health Center. We share faculty and have cross-teaching of dentistry and medicine. It’s much more of a collaborative and interactive environment here, and that has many advantages.”

At UConn, about 80 percent of dental students’ time is in the medical curriculum, which MacNeil refers to as the “combined curriculum.”

“There are only two other dental schools where this occurs, and those are Harvard and Columbia,” MacNeil notes. “We probably have a more interactive curriculum than any dental school in the country.”

“There are only two other dental schools where this occurs, and those are Harvard and Columbia,” MacNeil notes. “We probably have a more interactive curriculum than any dental school in the country.”

In 1990, the curriculum underwent its first major change since 1968. Dr. Eugene Sigman, who had become dean of the

medical school in 1984, charged Dr. Bruce Koeppen, newly appointed dean for Academic Affairs and Education, who has since left the Health Center, with leading a complete review and revision of the curriculum to prepare it for the challenges of the future.

“I told him at the time that this project would take at least seven years,” Sigman says.

Koeppen and a team of faculty members conducted an in-depth evaluation of the existing curriculum, explored curricula at other medical schools and discussed what an ideal curriculum, started from scratch, would include. The result was a new curriculum, implemented beginning with the 1995 freshman class. Under the new curriculum, still used today, students learn by researching and solving problems, rather than solely through lectures. They have more exposure to real patients beginning earlier in their course of study and, through an innovative program called the Student Continuity Practice, work with physicians in the community and gain experience following patients over several years. The school became one of the first in the country to used “standardized patients”—actors trained to represent someone with a specific disease—in training students. The new curriculum attracted national recognition.

Koeppen and a team of faculty members conducted an in-depth evaluation of the existing curriculum, explored curricula at other medical schools and discussed what an ideal curriculum, started from scratch, would include. The result was a new curriculum, implemented beginning with the 1995 freshman class. Under the new curriculum, still used today, students learn by researching and solving problems, rather than solely through lectures. They have more exposure to real patients beginning earlier in their course of study and, through an innovative program called the Student Continuity Practice, work with physicians in the community and gain experience following patients over several years. The school became one of the first in the country to used “standardized patients”—actors trained to represent someone with a specific disease—in training students. The new curriculum attracted national recognition.

“At the time, no other medical school had tackled a complete, four-year revision,” says Koeppen.

Dr. Peter Deckers, who came to the Health Center in 1985 and served as dean of the medical school from 1995 to 2008, says of the new curriculum, “It is a major educational change. Not all schools have adopted it, but the enlightened ones have. Our curriculum is relevant and responsive to the health care changes occurring in America. It has become a model for other schools to follow.”