Art in its various forms – from sculpture and painting to photography and, most recently, digital media – has moved, delighted, and sometimes provoked people. And pornography has been regarded by some as a source of erotic pleasure, while being denounced as offensive or even harmful by others.

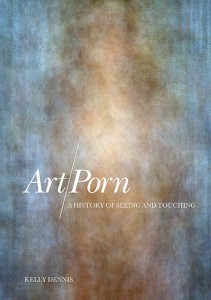

In her book, Art/Porn: A History of Seeing and Touching (Berg Publishers, 2009), published earlier this year, associate professor of art history Kelly Dennis explores the realm of art and its relationship to pornography. She looks in depth at how society has conceived of art and pornography in various forms over time – and how Western culture has come to create and maintain a kind of boundary between the two.

Dennis sets out not to define what is or is not pornography in Art/Porn, but to examine society’s conflicting discourses on and historical perceptions of art and pornography, looking back as far as ancient times and the Renaissance through to the advent of photography and, ultimately, the Internet age.

“My goals were to complicate what I think has become a safe distinction between art and porn – and the interests that has served,” Dennis says. “I’m less interested in distinguishing art from porn than in why everyone seems to want to distinguish between them.”

Dennis also examines the controversies over imagery – what has or has not been considered appropriate – through the ages, considering depictions of class, the female nude, and feminine sexuality from historical and political perspectives.

Seeing and Touching

Central to Dennis’ book is the role of the sense of touch in how people think about art and pornography. Between a work of art – for instance, a painting or sculpture – and the beholder, there remains a kind of centuries-old boundary or “long-standing tension” between seeing and touching, says Dennis.

Pornography, however, challenges that boundary. “Pornography indicates … the absence of a discrete limit between viewer and image, the instability of the distinction between subject and object of representation,” she writes in the introduction to Art/Porn.

Dennis maintains that this long-standing boundary between viewer and image has routinely been violated over the ages. For example, most people, she says, tend to think of Classical art as beautiful and remote; yet even as far back as Antiquity, viewers of artwork defied the separation between sight and touch. In fact, the first public nude depiction of a woman in Greek art, a sculpture called Aphrodite of Knidos, was known to be molested by male viewers throughout the fourth century BC.

With the arrival of photography in the 19th century, Dennis says, “the tension between viewer and image became more irresolvable.” Images depicted in photographs could be touched, held in one’s hand, or carried in a wallet – further “blur[ring] the line between sight and touch.”

“Part of the historical argument is that pornography began with photography,” she says.

At the same time, photography made artwork and erotic imagery – once accessible mainly among the elite – more readily available within the public sphere.

“Photographs could be circulated in a way that a painting or sculpture could not,” Dennis says. “There was an opening of the audience to seeing. Once it became available to the mass audience, it became ‘pornographic.’”

Researching Pornography

In conducting research for the book, Dennis consulted a wide range of sources, visiting museums such as the Museum of Sex in New York City, exploring public and private collections internationally, unearthing advertisements and photographic images, sifting through centuries’ worth of artwork, and studying amateur pornography on the Internet.

Although pornography has ultimately emerged as a scholarly subject, Dennis says “there’s also been a backlash – that it’s trivial, that it doesn’t belong in scholarly research or doesn’t deserve to be studied in the classroom.” Even within the discipline of art history, she has observed a certain resistance to studying the topic.

“Pornography is a topic that’s omnipresent, that shouldn’t be as scary as it is or cause the reaction that it does,” she says. “The book isn’t written to convince anybody that pornography is a good thing; it’s a part of our visual culture and deserves study and analysis.”