At four feet 10 inches tall, Davyne Verstandig can easily type on her computer while standing.

But author Frank Delaney pictures her on a football field with the entire offense of the football team barreling towards her. “She just puts her hand out and stops them by force of will,” he says. “She has the kind of personality that could stop a lynching.”

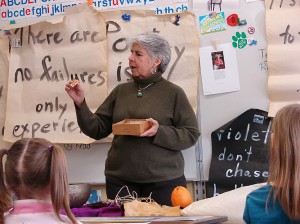

And that, he says, is precisely why she has been able to nurture the Litchfield County Writers Project (LCWP) so successfully that major writers speak with students and readers at the Torrington Campus on a regular basis.

Delaney, who has written non-fiction and fiction, worked for the Irish state network RTE and the BBC, and wrote the documentary The Celts, met Verstandig at a poetry reading the LCWP hosted at the Torrington Campus. He has since spoken several times in the program.

Reaching Out

The Writers Project is well suited to Litchfield County, where there are “more professional writers per square inch than any other county in the United States,” says Delaney’s wife, Diane Meier, a novelist and owner of an advertising agency.

“It takes an enormously courageous and audacious person to reach across the fence to say to William Styron ‘surely you want to be a part of this project,’ and Davyne does it.”

Verstandig sees Litchfield County as a 21st century Bloomsbury and herself as the life force making the connections, adds Meier.

The LCWP program consists of a 1,300-volume library with signed copies of works by Litchfield County authors – including the late Styron and the late Arthur Miller – and a display of photographs on loan from the Inga Morath Foundation. Morath was the wife of Miller and the mother of actress Rebecca Miller, also a part-time Litchfield County resident. The photographs focus on artists from Litchfield County.

LCWP also offers courses each semester on writing and a well-attended public lecture series. After the program received a gift of $100,000 last year, it expanded to include gallery space, and has begun a new focus on the creative process and the visual arts.

“Davyne’s support of local writers and artists is unparalleled,” says Julia Bolus, a literary assistant working with Arthur Miller’s papers, who is also a published poet and a teacher.

Verstandig is not unlike the people she pursues as speakers for the program. She is a painter, published poet, playwright, and novelist, and has been a secondary school teacher and college professor.

In 1995, she was hired at the Torrington Campus as an adjunct professor of English and soon began working on the Writers Project, since it was clear that Litchfield County is characterized by a high number of writers, and a project focusing on them would provide a way for the campus to distinguish itself.

Verstandig’s day includes an hour or more of reading – concentrating on Litchfield County authors, especially contemporary novels and memoirs – and time spent at Marty’s Café in Washington Depot, where many of the people she encounters are authors. One of them is Frank McCourt, the Pulitzer Prize-winning author of Angela’s Ashes and ’Tis, who has spoken several times for the LCWP.

One of her jobs is to design a new writing course every semester. And always, she is writing. Several times a week, her day ends with dinner with local authors whom she invites to participate in the program.

Connecting Writers and Readers

One of those writers is Roxana Robinson, who recalls that during one of her appearances at the Torrington Campus, she was introduced to a fan of her writing who had, with Verstandig’s help, been flown in from out of town as a birthday present to meet the author.

“Davyne is very interested in the connection between writers and readers,” says Robinson, novelist,biographer, and essayist, who has twice been part of the LCWP lecture series and has been interviewed on stage by Verstandig.

“She is a wonderful interlocutor,” Robinson says.

“I was struck by how much research she had done, and by how carefully she had read my work.”

A Varied Career

Originally from Hamden, Conn., Verstandig was educated in the South, receiving her master’s degree from the University of Tennessee in the 1960s.

Her time there includes many recollections indicative of the turmoil in the U.S. at the time.

When she marched in a civil rights demonstration in Knoxville, she was spit on by whites.

And when she asked permission to take a class in the Modern African Novel being taught at a local black college, she was refused. No credit could be given, she was told, for courses at such an “inferior” institution.

She took the class anyway. When Robert Kennedy was assassinated, she knew she was done with the South.

Heading home from college with her mother, the two were in a car accident that killed her mother.

“Everything changed in that moment,” Verstandig says, and rather than heading to New York to seek a job in publishing, she returned to Hamden.

Someone suggested she might try teaching. Unaware that she needed a teaching license, she secured several jobs.

She chose one in Shelton because the students were from blue-collar factory families, as different as possible from the students at her high school, Rosemary Hall, then located in Greenwich. She knew it would be a challenge.

She also taught at Central Connecticut State University and Albertus Magnus College, at Newburgh Air Force base, and Fort Totten in Queens, N.Y.

And she directed and acted in plays at the Creative Arts Center – now Theaterworks – in New Milford, Sherman Playhouse, and Dramalights in Washington, Conn.

She eventually opened a book store in Washington Depot, and later in Warren, Conn.

It was her hairdresser, a UConn Bachelor of General Studies student, who recommended she teach at the Torrington Campus.

Today, Verstandig sits in her office there under one of her acrylic paintings – a three foot by five foot abstract that proclaims, “Obstacles are the vehicles by which we move forward.” She notes that at age 64, she has no plans to retire.

“Teaching is the best profession there is,” she says. “Every day, one can make a difference.”